TRAVIS STEWARD

Travis grew up in the small farming community of Tremonton, UT. His parents both had had previous marriages and children before he was born, making him the eighth of ten kids total between them.

“As a kid you don’t know how families are supposed to be, you just are there trying to find your place and figure it out as you go along,” he says. Still, he knew his family definitely didn’t fit the mold of the strong LDS community in Tremonton. Though his parents and stepparents had their own challenges, Travis shares that he knew and felt love amid the chaos and uncertainty that plagued his young, anxious heart.

Long before he realized that he was same sex attracted, he knew that he was different from the other boys in school, including his five older brothers. “For some reason I couldn’t relate very well to them and was confused by much of what they said and did,” he says. Most of his interests, thoughts, and ideas were different from what he saw around him. “I often felt that I had to keep them quiet out of fear of judgment or criticism. I will spare the details, but I felt that I had experienced more than my fair share of tragedy by the time I had finished high school.”

Around age 12 or 13, he began to experience a very strong interest in certain boys on the little league football team. It wasn’t anything sexual or romantic, he had no clue what those feelings were yet, but says, “I wanted to be around them and have their attention and found them to be beautiful to look at.”

Like most teens headed into puberty, it can be a very anxious and worrisome time. Travis began to pick up on the conversations, expectations, and judgments that freely flow in any junior high or middle school. “I began to hear the negative comments and see first-hand the bullying of another boy a year older than me for being gay, though that was not the term used 50 years ago. I suspected that I was experiencing the same attractions that this boy felt, and I could see how terrible it would be if anyone were ever to know or even suspect the same about me.”

This began a very long and painful journey into hiding, performing, and self-loathing over the next 40 years.

After graduating high school, Travis became active in the church after rooming with two recently returned missionaries. They inspired him. “They were very disciplined, and this example and the rules and organization of the church was very appealing to my desire for something more predictable and stable.” Travis adopted these mannerisms to lead what appeared to be a good and honorable way of life.

He also became more aware of the harshness and disgust towards homosexuality expressed by adults around him, and the notion that this type of sexuality was a choice. Travis wrestled with learning he must be choosing his sexuality while simultaneously abhorring it. He recalls his mission to Chile as a respite from most of this worry. “I felt free from the shame and anxiety associated with anyone finding out or suspecting.” The feelings of confusion, shame and fear quickly returned when he returned from his mission, and while at BYU and working at the Missionary Training Center. He felt condemnation everywhere--from his faith community, his church leaders, and from God.

Looking back, Travis recalls it was the ease of friendship and safety with girls that contributed to his awkwardness approaching physical affection with them. “Though I was homosexual, I will say that I had always planned to marry and have a family and looked forward to that next part of life. The thought that I couldn’t or shouldn’t had never crossed my mind.” He had always felt an interest in girls, but it more so revolved around their humor, intelligence, and common interests than in their beauty or bodies. In fact, he judged other guys who seemed to be obsessed with flirting, making out, and sexual inuendo, feeling he was above that type of inappropriate behavior. “I was fortunate to find someone like Margaret who was kind and patient as we dated and gave me ample space to learn and grow as I awkwardly navigated that first kiss.”

He knew what the societal expectations were for dating, engagement, and marriage should look like—especially in an LDS culture. Travis has been asked why he didn’t tell Margaret he was gay before they were married. “The truth is, I did not believe that I was gay, myself. I assumed that I was being tempted or that I was confused or just inexperienced.” It was a different world back in the early 1980’s, and the idea of hiding in a marriage or marrying to fix it never crossed his mind. “I knew I loved her, and she was my very best friend, and I had no doubt that we would have a wonderful marriage.”

By the time they married in August of 1985, Travis was already deeply entrenched in hustling for self-worth. He felt terrible and ashamed of this secret he was hiding, and service became a drug of choice. He explains, “I felt that I could hide from my own worries if I could worry about somebody else’s.” He became a natural fit for and was often asked to serve in leadership capacities at church almost constantly for the next 30 years. Their family has an inside joke that Travis never thought there was ever a problem with their six kids in sacrament meetings, because he never sat with them! After serving in the stake presidency for nearly 12 years, Travis and Margaret were asked to serve as mission leaders in 2004. He was 41 at the time and their kids ranged in age from 4-18. Travis says, “The mission was one of the most joyous and fulfilling experiences of my life. I hope that something wonderful came from it for others as well.”

Immediately after returning from the mission, Travis was called as bishop of their home ward. He served faithfully for five more years—giving everything he had while continuing to carry a part of himself in silence. Spiritual growth came hand in hand with spiritual pressure, and the more he was trusted, the more he felt he had to lose.

When his time as bishop ended, Travis entered what he calls “the first real period where I couldn’t just bury myself in a calling to hide from it all.” Without the structure and distraction of leadership, the internal conflict became harder to ignore. “I think God had finally had enough of watching this turmoil play out, and it was time to look at it.”

For months, he experienced persistent, intrusive thoughts about telling Margaret about his same-sex attraction. Then one Sunday morning, without planning or warning, the words came out. He simply couldn’t hold them back any longer. “Fortunately for me,” he says, “Margaret was able to hold such a revelation—backed up by 40 years of shame and pain—with so much love and compassion, it was never a question about not continuing in our marriage.”

But Travis was blindsided by what followed. Rather than the relief, finally getting this secret off his shoulders ushered in a slow, rising tide of grief and pain. He frantically tried to get back to that place of manageable denial. Until that moment, he had managed to compartmentalize his homosexuality—as a trial, a temptation, a weakness to be conquered. Having said it out loud it could only be compartmentalized as reality. “I felt I had lost the biggest battle of my life and now that it settled over me, the reality was very nearly too much for me to bear.”

The next couple of years were a blur of sleepless nights and hours of therapy. Central to Travis’ secrecy was the fear that with coming out now, he’d lose everything—his marriage, his career, his callings, and friends, and looking back on his journey – nearly everything he worried could happen if people found out he was gay, did. “I had a lifetime of reasons to be afraid of the fallout that I anticipated would come with coming out. I was still not prepared for the devastating blows of prejudice and discrimination in losing my career, important relationships, and all the rest of the privileges that came with being perceived as a straight man.”

Travis remembers thinking he’d probably struggle for a few months and then be over it all and feeling better. Travis says. “It’s a good thing I didn’t know then it would take years to find some footing as a gay man.” Over the past few years, he’s both participated in and helped lead support groups for gay men in Utah and beyond, both online and in person. Along the way, he’s come to see how human nature tends to complicate healing. “It’s difficult—and terrifying—to share your deepest, darkest truth with the people you love while worrying they might stop loving you because of it.”

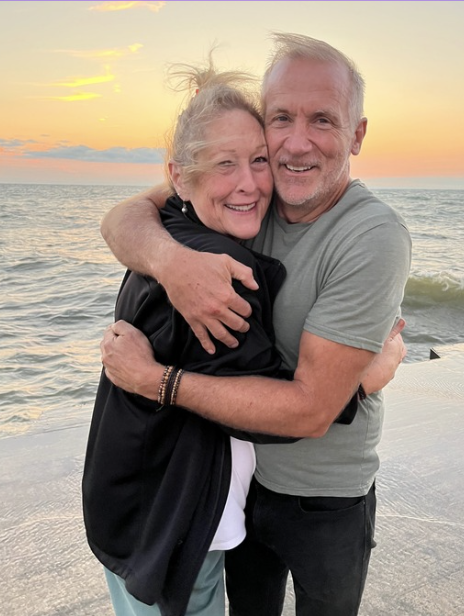

But on the far side of that long-anticipated loss, Travis was surprised by something else. “I wasn’t prepared for the peace that exists without shame.” These days, he tries to value the journey without fixating too much on the destination. And after all the fear and silence, he’s found that being queer wasn’t the hard part. “The hardest part has been dealing with what other people think being gay must mean for and about me. Those meanings are hard to shake, but I manage okay now.” The same goes for his marriage. “We’ve had nearly 40 wonderful years together,” he says. “We’re happy—until we let other people’s opinions about mixed-orientation marriages get into our heads.” To Travis, it’s bewildering that so many feel entitled to weigh in.

He is determined to be himself. “I have a wonderful family. I have gay kids and family members, and it’s no big deal in our home. But as a man in a so-called mixed-orientation marriage, I’m too gay for the church, and not gay enough for the LGBTQ community. I’m in the 'lost boy zone,' feeling illegitimate on both sides.” That liminal space taught him something about compassion. "I’ve become a safe-space guy in the trenches. That’s my niche. To be the person I needed. To tell others: you’re going to be alright.”