MARGARET STEWARD

We previously shared Travis Steward’s story of being a gay man and former mission leader who came out after many decades of marriage. To read that story, click here

This is Margaret’s Steward’s story…

Margaret Steward didn’t grow up imagining she’d one day be the wife of a mission president, or the woman quietly fielding whispers after her husband came out as gay. She was born in Nephi, Utah, into what she calls “a super LDS community,” but her family stood slightly off-center from the mold. Her father was a 36-year-old small-town bachelor and partygoer when he met her mother, a 27-year-old schoolteacher. “They hooked up, got pregnant, and married. My mom didn’t want to be married,” Margaret recalls. “My sister always suspected my mom was a lesbian. Their whole marriage was a struggle.”

From a young age, Margaret understood what it felt like to live on the margins—not active LDS, raised in a turbulent household, constantly aware of difference. “My mom was a true original feminist who loved being in her skin—confident, capable,” she says. “My dad was a traditional white guy from small-town Utah. They were always going to get divorced, but they didn’t. They found a way to acclimate to each other.”

After high school, Margaret earned her associate’s degree from Snow College and—like “all good Snow College Badgers”—headed to Utah State. A friend asked if she’d ever thought about serving a mission. She resisted, having a boyfriend already out on a mission. But the minute she actually considered it, she felt the idea implant into her heart—while equally terrifying her. Despite that fear, she submitted her papers and was called to serve in Denmark—later learning through 23andMe that she was 55% Danish. “It felt divine. I had ancestors who served there in the 1800s. I was the fifth sister missionary sent to Denmark in over 20 years. It was an amazing experience.”

When she returned, Margaret moved to Provo, low on funds but full of momentum. She was living with former roommates and a mission companion while working retail when she met Travis Steward. Her former mission companion fell madly in love with one of his roommates, so the two got thrown together.

At first, romance was the furthest thing from Margaret’s mind. She was on a dating break and says she liked hanging out, but not like that. She wasn’t exactly leaning in. But Travis liked being with Margaret and said he could see himself marrying her, though he’d never had a girlfriend before. “I thought he was just a shy and inexperienced guy,” she says. “But being together felt comfortable. He’d always wanted to be married and have a family. And we enjoyed each other.”

The two got engaged and married within a few months. Travis worked at the MTC, and Margaret continued working at a department store. She got pregnant right away. “I wanted to be married but was terrified of kids,” she now admits. “It was just me and my sister growing up—no nieces or nephews. Little kids terrified me.” But Travis stepped in so naturally. “He was amazing with them. A great helper.”

Over the next four decades, they raised six children and served in high-level church callings, including three years as mission leaders in Houston. They took along their kids ages 18 to 4. Of that experience, Margaret says, “It was exhilarating and exhausting. But we loved it. We mourned every time a month would conclude knowing we had that much less time with the missionaries.” Their youngest children became immersed in Texas life, where they said their own version of a state pledge and made lots of friends and core memories.

Though she embraced the church callings that came their way, Margaret felt she never quite fit the “homemaker” mold. She says, “It was thrust upon me. I loved adventuring with my family, and I was irreverent at times. I paid attention to the way other mothers were doing things and worried that I was not doing it right. But the kids are alive. They survived.”

Margaret has taught in a range of church capacities—institute, Relief Society, Gospel Doctrine—and always approached those roles with thoughtfulness. But after they served as mission leaders and then as bishop for five years upon their return, when Travis came out publicly, things shifted. “There was a quietness after,” she said. “I was teaching seminary. He was in a student stake high council. People didn’t know what to do with us. Mostly because of what they’ve been taught—what it means to be gay or bi or whatever—and that you can’t lead if you are. Too risky. As if we aren’t all a risk at any given time.”

Still, she saw that most of it wasn’t rooted in malice. “I appreciate that people just don’t know what to do. It’s what they’ve picked up from the culture, not from a desire to be cruel.”

When asked what it was like to learn that her husband was gay after decades of marriage, Margaret says, “I’m an open book, sometimes to a fault. Some people don’t need to hear it all. I didn’t know what was there with Travis. There was just… a bit of a gap. Like I couldn’t fully see him. When he came out, I realized: that was it. That was the gap. He couldn’t show me all of who he was.”

She remembers the day clearly. Travis had been carrying the truth silently for some time. “He related that he felt the strong impression to tell me, but he didn’t want to. One Sunday morning, he closed our bedroom door and said, ‘I need to talk to you.’ Usually, it was me confessing something,” she laughs. “But I looked at him and the thought came, ‘Whatever comes out of his mouth, just hear it and accept it. Don’t assign meaning’.”

When he told her, she didn’t flinch. “I saw the man I’d loved for 30 years,” she says. “And I thought, I want to help hold this.”

There were complexities, of course. Travis was deeply closeted and had internalized years of shame. “He was terrified,” Margaret remembers. “But I had received this clear directive from the Holy Ghost: Here’s what you can do to help.”

The following two years were some of the hardest. Their shared life had been tightly interwoven through church service, callings, and community. But Travis lost his career after decades of devoted effort and investment. The loss was devastating. “Everything he feared came true,” Margaret says. “But eventually it got better. He was able to accept the truth of his experience without making it mean something dark.”

For Margaret, acceptance came more easily. “I didn’t have a lot of narratives to unravel. I’ve always believed that any person can find themselves on the margins at any time,” she says. “Our brains crave simplicity, but real life is more nuanced. God’s creation is expansive.”

Margaret also never defined herself as an “ally,” and still doesn’t. “Let me explain my thinking with that. Truth stands on its own merits I wonder when I hear someone speak of defending the truth. In my opinion, the truth doesn’t require defending. Simply because it is the truth. What our LGBTQ+ brothers and sisters experience is a lived truth. Exactly like our own. Nuanced, varying, and ever evolving as we experience and learn. No one has the answers as to how we arrive at the manifold attractions we experience.”

Her views on identity are similarly fluid. “While I recognize the need to orient ourselves in this mortal experience, we far too often simplify that process by sticking to polarities. Righteous-wicked, gay-straight, female-male, strong-weak, etc. Labels can be helpful for some, but for others, they become cages. I want people to be free to define themselves—and to change as they learn more about who they are.”

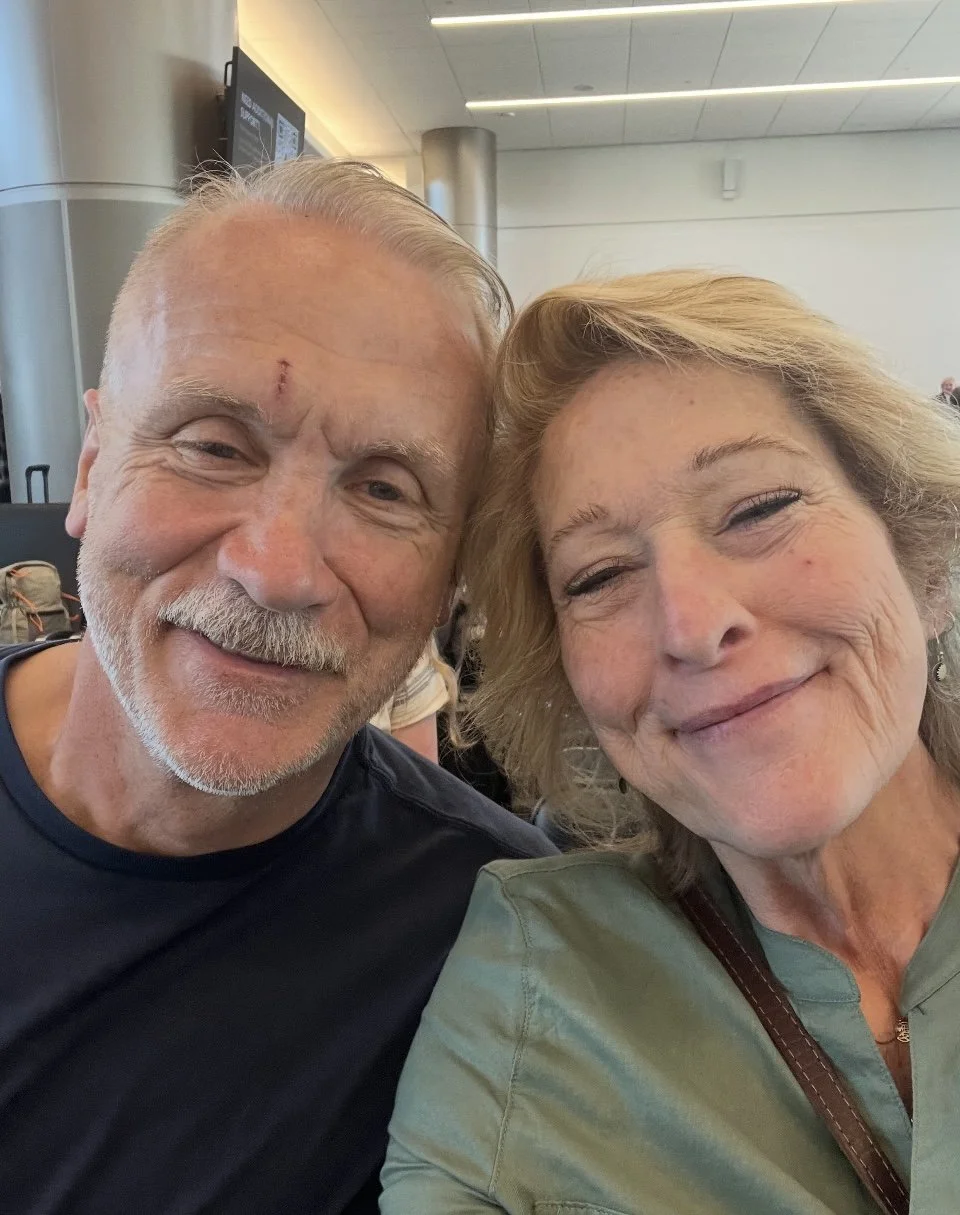

She also doesn’t lead with the term “mixed-orientation marriage,” yet because she recognizes there are more resources out there for parents of LGBTQ+ than for spouses, she tries to be a resource when asked. She and Travis remain married, still deeply connected. They spend much of their time adventuring together, also sharing those adventures with their kids and grandkids, especially at their off-the-grid cabin. One of their sons is gay, and Margaret’s sister is a lesbian married to a woman. Several others in their extended family fall along the LGBTQ+ spectrum. “From a young age, I just knew LGBTQ people were normal,” she says. “Growing up with friends and neighbors in my own small town, and my mission and college experiences only confirmed that.”

She recalls reading The Miracle of Forgiveness as a teen and bristling at President Kimball’s framing of homosexuality as "deep, dark sin." “I remember thinking of my sister and others I loved and just knowing: that wasn’t true.”

Margaret now works part-time as a receptionist at a therapy clinic for children and families. “I’ve always loved therapy,” she says. “Didn’t get a degree in it, but I’ve learned a lot just by being around it.”

She has been to a few LGBTQ conferences over the years, including one where she remembers looking around and thinking, “I will rejoice in the day when people don’t need a conference to legitimize their existence. Similarly, I never felt I needed a man in my life to feel whole. I haven’t viewed myself as half of anything. Nor have I had interest in attending events solely for women.” Still, she’s grateful those spaces exist. “I know not everyone was raised by strong women like I was,” she says. “Some people need those spaces to heal from their trauma.”

Margaret’s hope is for more curiosity and less programming. “Recently on the beach in Mexico, we met a beautiful trans woman and her wife,” Margaret recalls. “She was testing the waters to see if we were safe. When she learned we were still married after Travis came out, she was shocked. Even within LGBTQ+ spaces, we carry assumptions. We pick up narratives and use verbiage that is fraught with restricted thinking. I wish we could all be more open, more curious. More humble.”

At 64, Margaret has shed the need to define things too rigidly. “Life is too complex for boxes,” she says. “I thank my Heavenly Father for giving me the life experiences I’ve had. I don’t have to understand everything. I just need to love people. That’s enough.”