lift+love family stories by autumn mcalpin

Since 2021, Lift+Love has shared hundreds of real stories from Latter-day Saint LGBTQ individuals, their families, and allies. These stories—written by Autumn McAlpin—emerged from personal interviews with each participant and were published with their express permission.

THE AHLSTROM FAMILY

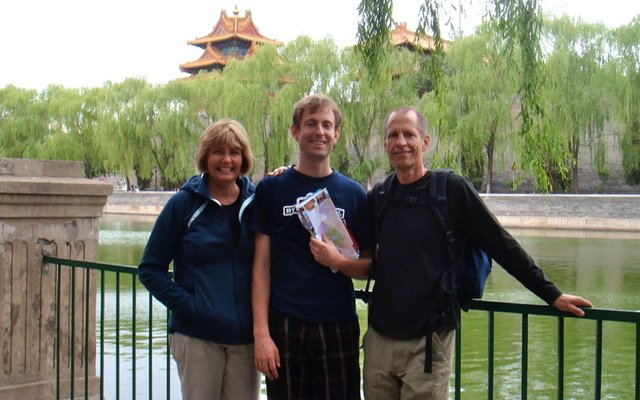

Char Ahlstrom of Los Alamitos, CA knows what it feels like to “do all the things.” She and her husband Tom had devotedly raised their six kids in the LDS faith where they both served faithfully in the church. In fact, Tom was serving as their stake president and Char was teaching early morning seminary in 2014, the year they found out their fourth child, Kyle, was gay. Soon after, Char read a message on an open computer screen that made her wonder if her youngest son might be gay. Char is the first to admit they perhaps did not initially handle these news flashes as well as they should have. But she now often shares her story of growth and shifting perspective, hopeful it may ease others on similar journeys who realize doing “all the things” means nothing if they lose sight of what it really means to love.

Char Ahlstrom of Los Alamitos, CA knows what it feels like to “do all the things.” She and her husband Tom had devotedly raised their six kids in the LDS faith where they both served faithfully in the church. In fact, Tom was serving as their stake president and Char was teaching early morning seminary in 2014, the year they found out their fourth child, Kyle, was gay. Soon after, Char read a message on an open computer screen that made her wonder if her youngest son might be gay. Char is the first to admit they perhaps did not initially handle these news flashes as well as they should have. But she now often shares her story of growth and shifting perspective, hopeful it may ease others on similar journeys who realize doing “all the things” means nothing if they lose sight of what it really means to love.

When Kyle, now 32, first told his mom (six months after returning home from his mission) that he was bisexual, she says she wasn’t entirely surprised. She’d had inklings, but never talked about it. She observed he liked girls in high school, but never had a girlfriend. Whenever other possibilities presented, Char says, “I always pushed it away, believing, ‘I could never have a gay child because we are doing all the things in church’.” She’s embarrassed now to admit that at the time Kyle came out, she and her husband told him to just “keep up the façade”--that if he was bisexual, he could still remain active in the church, marry a woman, and pursue that path.

A few months later, when Kyle revealed he was actually gay, not bi, he still wanted them to believe he intended to marry a woman and stay in the church. In the months after his mission and during what he calls “the days of growing darkness in my soul,” Kyle visited the Salt Lake Temple often. He says, “I did as Nephi had done, ‘I arose and went up into the mountain, and cried unto the Lord.’ I did not go to ask anything particular of God, I wasn’t looking for permission to come out; no such endeavor was in my mind. I knew the path and the promises I had made and was committed to keep them even unto death, which with suicidal ideation, was coming quicker than it should. I simply went to the temple to cry, knowing I needed the Lord’s strength to carry on.”

While participating in an endowment session, Kyle says his mind wandered to a place it hadn’t before. He clearly saw his own wedding day, and to his surprise it wasn’t in the temple and it wasn’t to a woman. Kyle says, “It was to a talk dark haired man; we stood hand in hand under an oak tree near a pond. Feeling this fantasy must be a temptation from the enemy, I cast the thought out of my mind, trusting it had no place in the Lord’s house.” But the vision came back two more times. Kyle dutifully pushed the thought out a second time but by the third, he says, “The scene had rested upon my mind so gently, the way a parent’s guiding hand might lightly aid a child learning to walk, that I didn’t notice the delight of a smile, pure and powerful, had stretch across my face for the first time in months. And I heard a voice say only the word ‘Yes’.” That permission through revelation received in the mountain of the Lord’s House softened and sustained Kyle’s heart. He says, “I had been visited three times, and knowing what happens when you deny the Lord three times, I determined I would no longer bitterly weep; I had made enough of that noise. I knew from that moment on with the conviction of Moses taking off his shoes before the burning bush that my promise and my path now was to put off the shame I had been steeped in for years, was to welcome this new and everlasting vision for my life, and was to say only ‘Yes’ to love.”

Other facets of his story are “his to tell,” says Char, but this was a time in which they worried about his mental health as he struggled with depression, anxiety and suicidal ideation. An eye-opening, life changing moment for Char was when one of her sons said to her, “I’d rather have a gay brother than a dead brother.” That’s when Char started to realize as much as she loved her son, she needed to find a way to accept and support him better. Kyle started seeing a psychologist and started medication. Soon after, he started making his way out of church. The family started noting positive changes in Kyle as he seemed happier and more at peace with himself. As he started dating men, Char remembers “kind of wanting to know” details about his dating life, but feeling too scared to ask. One day, Kyle said, “Mom, if you want to know something, you’ve gotta come straight out and ask.” For her, it wasn’t easy, but she did. Since, she’s been able to have open conversations with both of her gay sons about everything from dating concerns to HIV prevention best practices, which she appreciates.

While Kyle opened Char’s mindset, it was still very hard for her when she discovered the boy her youngest son, Keith, had been messaging was actually his boyfriend. She admits she “did not handle things very well. At the time, I thought, I’m dealing with one son who is gay who I’m loving and supporting, though not happy with all his choices. And now I have another?” Char remembers trying very hard to push both her gay sons to stay active in the church, believing that while the Savior wouldn’t change this part of them, that He would “lead them in a better direction than I thought they were heading. I was so scared and worried for them and couldn’t believe this was happing to us. We were that typical, conservative Mormon family.”

The night Keith told Tom and Char that he was gay, she opened her scriptures to D&C 78:18 and read: “You cannot bear all things now, nevertheless, be of good cheer for I will lead you along.” Char says it was such a comfort that “God did know how hard it was for me!” She struggled with how to be of good cheer when it seemed like things were falling apart. But, as a seminary teacher, when she learned that in some translations “good cheer” meant “have courage,” she says, “then I realized that’s what He was telling me – to have courage and He would lead me along and I wouldn’t lose my eternal family, which I was worried about. He did lead me along; he led me to new thoughts and ideas and people to reach me. After many years, I see very clearly how God has led me along.” Later in the temple, Char contemplated another rift in testimony she’d experienced, now believing that her children were gay and that wouldn’t change with any amount of therapy. So if that was true, and knowing what the church taught, she wondered if God actually did make mistakes. But in the temple that day, she was told the only thing she needed to do was to love her children and trust that God loved them.

At the time, Char was experiencing turbulence with all her kids – including some moving around the world and three of the six leaving the church. One day, she was listening to a podcast on which Tom Christofferson shared that what children need is for parents to both love them and accept them where they are. That was a switch in Char’s thinking, having believed people needed to do certain things to be met with approval. She explains, “So I didn’t feel I could love them where they were because it wasn’t where I wanted them to be. But the Spirit said, ‘No, you need to see them where they are and love and trust that they’ll make decisions for their life that are best. They’re not alone.’ The biggest change for me was to accept them and their decisions.”

Char says she was taught by the Spirit and came to understand that Kyle and Keith were not some kind of mistake. “I was taught that who they are, who they love, is exactly how God made them. Their sexual orientation is not something they need to endure in this life, and it will be gone in the next. That was a huge revelation to me and changed everything going forward. That understanding, for me, took much of the fear away. I personally came to understand that a loving God will include ALL. So when he said, ‘It is not good for man to be alone,’ it meant ALL humans in this world. I think eternity is going to look much different, way more expansive than we are taught. I have asked in prayer many times if I am wrong, deceived even, and every time, I get the same answer: ‘No, you are not deceived’.” Char loves that so many other parents express they’ve been taught the same about their LGBTQ kids. “I’m not alone!”

Around this time, Char’s husband was released as stake president, and despite Keith no longer participating in church after a rough semester at BYU-Idaho, he was invited to lunch by the new Long Beach stake president, Emerson Fersch, who said he just wanted to get to know him. Char says President Fersch was so kind and loving in response to Keith telling him he was gay, and asked him to speak at stake conference and share his experience. Keith didn’t want to do that, but after receiving a warm, knowing hug from their new leader in the hallway at church, Char suddenly had an impression she should speak at stake conference. Turns out that inkling manifested when she was soon after asked to speak about her journey as the mom of two gay kids.

In front of her stake, Char shared the nuance and cognitive dissonance she’d developed, and afterwards, many confided in her that that was also their experience. One man reached out to say, “I have a daughter who’s a lesbian and I don’t speak to her anymore. What do I do?” Char replied, “Call her! Still today, people call me for advice.” When asked to speak in Elders Quorum a few years ago about her experiences, an 85-year-old man raised his hand and acknowledged, “If I’m understanding this correctly, you’re saying WE need to change, that our hearts need to change and we need to be more loving?” Afterward, another man came up and said, “I understand what you’re saying but that’s not what the church is teaching.” Char replied, “Welcome to my world.”

Under President Fersch’s leadership and efforts by families like the Ahlstroms to have LGBTQ+ FHE and ally nights, the Long Beach stake became known as a friendly place for members who’d been pushed out of other congregations. When Covid shut things down, the groups stopped and they unfortunately have not restarted with a new stake presidency. While they still attend church as visible allies, Char says most of her and her husband’s interactions with other parents in their situation happen one-on-one.

While living in Utah, Kyle started to date one young man in particular. At first, Char felt scared to meet Chandler because she knew Kyle really liked him, but after she got to know him, she had no doubts this man was good for Kyle and she says she could see him as a “part of our family.” The shock of this realization made Char reflect, “What an interesting journey I’m on.” After dating for five years, in 2020, Kyle and Chandler married not under an oak tree by a pond but under the redwoods by a stream, with all the Ahlstroms in attendance. Char knew she supported it financially and emotionally, but wondered how she’d feel spiritually. She’d read an article about a BYU professor who wrote about how he’d felt the spirit at his daughter’s wedding to a woman, and Char says at her own child’s ceremony, she also “felt God’s love there.” Now when she looks back on the rhetoric she used to believe, how gay marriage would be “the downfall of our society and wreck traditional marriage,” Char reflects on all she’s learned watching Kyle and Chandler, who “go to work, come home, plant a garden, take care of their house, go for walks with their dogs” as they build a life and family. Kyle works as a photographer and Chandler is an event planner who has worked at Sundance. They love living near the mountains and getting outside in Utah where they reside.

Back in California, Keith and his partner of four years, Derek, live in Los Angeles, where Keith works for a production company, and Derek is a “very talented” filmmaker and director. Their relationship started as roommates when they both moved into an apartment with a woman. While Char was first apprehensive about who Keith might date in LA, she now says, “Derek is part of our family.”

Of her growth, Char says, “One thing I look back on now is how I was scared to be curious, to ask questions, because I didn’t want to hear answers. But now I see how wrong I was. They wanted me to ask questions, to want to know. I advise parents not to be afraid to be curious, to ask questions and try to understand where they’re coming from. Your kids are still the same people they were yesterday or before you found out they were LGBTQ+. Love them, accept them as best as you can. Trust them.” Recently, a man approached Char for advice about his trans daughter. She put him in touch with other friends with trans kids and advised him to “accept her, call her by her preferred pronouns, do all you can to love and accept her for who she is right now. God will give you peace about that.”

As most parents do, Tom and Char think that all of their children are wonderful people and greatly respect each of them. What was once fear and worry about Kyle and Keith has grown to a vast appreciation for everything those two in particular have taught them about love for everyone.

The exclusion policy of 2015 was the first time Char had ever questioned a prophet, and she says this has all made her look at leaders differently, and taught her it’s okay to question things. Now she has three children out of the church who maybe sometimes wish their parents weren’t so active (one of them jokes, “hate the sin, love the sinner” regarding his parents’ attendance at a church he finds non-affirming). But the Ahlstroms remain close, and siblings Kevin and his wife Bree, Krista and her husband Tallon, Kasey and his wife Didi, and Kenny, as well as Char and Tom’s seven grandchildren, all embrace Keith and Kyle. They gather every year for a reunion, where Char says they enjoy being around each other and she especially likes the brothers’ fun competitiveness. Nowadays, the Ahlstroms’ list of doing “all the things” prioritizes love, togetherness, and inclusion.

After her kids first stepped away from the church, Char learned how to respect their various journeys and to trust they’d all find their best paths forward. But she worried that first year about how to handle things like holidays and mealtime prayer and family Christmas traditions, which had once been so spiritually centered in their home. She didn’t want to offend or alienate anyone. Recently though, when Char talked to Kyle about coming home for Christmas this year and which traditions she could incorporate to “not make it weird,” he assured her, “I’m better with that stuff now. We can do the Nativity. I kinda like that story.”

THE GILES FAMILY

The crux of the LDS-LGBTQ+ dilemma is most frequently characterized by the perception of three limiting life paths when one comes out as gay: 1) Stay in the church and live a celibate life. 2) Enter a mixed orientation marriage. Or 3) Date and allow yourself to fall in love according to your attractions, and necessarily leave a church you may still love and value. But what about when none of these options feels like the right fit? What if you choose to carve out your own way by entering a same sex marriage while still showing up to your faith community of choice, even when its underlying teachings seek to minimize your union? For Liz and Ryan Giles of Yakima, WA, that is the exact path they’re navigating right now, and their new Instagram account @the.fourth.option’s rapidly growing following suggests many others are also intrigued by this option.

The crux of the LDS-LGBTQ+ dilemma is most frequently characterized by the perception of three limiting life paths when one comes out as gay: 1) Stay in the church and live a celibate life. 2) Enter a mixed orientation marriage. Or 3) Date and allow yourself to fall in love according to your attractions, and necessarily leave a church you may still love and value. But what about when none of these options feels like the right fit? What if you choose to carve out your own way by entering a same sex marriage while still showing up to your faith community of choice, even when its underlying teachings seek to minimize your union? For Liz and Ryan Giles of Yakima, WA, that is the exact path they’re navigating right now, and their new Instagram account @the.fourth.option’s rapidly growing following suggests many others are also intrigued by this option.

Like much of their relationship, Liz and Ryan’s wedding was off the beaten path—literally. In August of 2021, about 100 of their close friends and family joined them in the Washington wilderness at Camp Dudley—a summer camp Liz had been involved with since 2009 as a camper and later counselor and teen director. Ryan had always felt typical wedding receptions were “boring,” so they offered their guests the option to go boating, rock climbing, ziplining, and do archery during their special weekend. After their ceremony, Liz and Ryan stole 15 minutes for themselves, and stepped away from the crowd to a secluded place on the shore to pray together and have their own form of a covenant making ceremony in nature, an experience they loved.

It was the perfect setting for former high school English teacher, Liz—25, who now runs year-round outdoor education programs for fifth graders. Ryan—28, and originally from South Jordan, UT, is an EMT and was just accepted into an occupational therapy program after which she hopes to work in pediatrics helping kids to navigate the emotional and physical connectivity of their health. Together, the two love to do puzzles and play board games like Parcheesi and Scrabble, as well as go rock climbing, explore parks, and “chronically rewatch TV shows” like Schitt’s Creek, the Fosters, Gilmore Girls, The Good Place, Jane the Virgin, and Grace & Frankie. Currently pup parents of dogs Kevin and Casper, Liz and Ryan are currently finishing up their home evaluation to become foster parents. They say they would love to foster-to-adopt sibling pairs who often struggle to stay together, and are also supportive of the reunification track for kids who benefit most from that route.

Liz and Ryan have realized a love that over the past seven years has at times felt complicated. For some in the wards they’ve attended as a gay married couple, their union does complicate some’s sense of “how we do things.” But Liz and Ryan hope that their openness about their marriage will help others, especially LGBTQ+ youth or closeted adults who want similar things, to view it as a possibility, while also helping those for whom gay marriage is uncomfortable to warm to the idea that “their agenda” in attending church doesn’t vary from the average person’s objective to show up to find community and draw closer to Christ.

The Giles’ story started with a meet-cute in 2016. Liz was a freshman at BYU and her roommate had gone to high school with Ryan--who had just returned from her mission and moved in next door. For months, they were just friendly-ish neighbors, but Ryan had never fully caught Liz’s name and after three months, she says, “It felt too late to ask.” Ryan didn’t think she’d see Liz enough for it to matter, but Liz says, “Like a Whacamole, I just kept popping up.” As the friend group continued to hang out, the following semester they all moved into an apartment together where game nights frequently involved improv comedy skits in which Liz and Ryan would draw scenes from a hat and have to act them out. Liz says, “But we’d always draw scenes in which we had to act like a couple. So then as a joke, we started calling each other babe like we were a fake couple within a roommate context.” Ryan adds, “And then, it became less fake than we thought it was.”

The next few years were filled with navigation as the two individually figured out their orientation, their attraction to each other, and their other life plans. As Ryan headed to Paris for a study abroad, and Liz left several months later to serve a mission, they both tried to convince themselves that this was all just a fluke, that they were still straight (Liz thinking this more so than Ryan), and that maybe, sometimes these kinds of things just happened with roommates? Nine months into her mission, Liz came to the realization that her feelings for Ryan (and, on a bigger scale, her same-sex attraction) were not a fluke. After Ryan returned from her internship in Paris, and while Liz was still on her mission, they came out to each other and acknowledged that what they’d felt was real. This didn’t exactly make Liz’s church service easier. At the time, Liz was spending her days with a mission companion who loved to recite the Family Proclamation while they drove around their (very large) area. Although she loved many things about this companion and their several transfers together, she knew that kind of setting was definitely not a safe place to come out. Yet it still took her nearly a year after her mission to realize that she did not want to pursue option one or two in her life—that while she longed to have a family and be a mother, Liz did not want to deny herself a relationship filled with chemistry and deep love.

When Liz returned, Ryan was patient and careful not to put any pressure on Liz. Ryan had already come out to her parents “accidentally” after she was watching general conference with her brother and dad and a speaker focused on what to do when you feel “the Lord is asking too much of you.” Seeing his daughter become upset by this, Ryan’s dad prodded her to be more specific about what hardships she was facing in a big, long discussion of which Ryan says, “My dad was amazing.” This was a welcome surprise, and the next day she came out to her mom who had a harder time at first, but who she says has also been amazing. Ryan remembers fondly that one of the first questions she asked Ryan was, “Does that mean you’re going to have to cut off all your hair?” Ryan laughed and replied, “That’s not required anymore; we’ll leave that be.” As Ryan continued her schooling at BYU, she felt it wouldn’t be safe to risk her diploma by coming out publicly, so she quietly considered her future options, none of which felt right. Before she’d come out to her parents, Ryan says she’d felt sick to her stomach for months before getting a priesthood blessing from her dad in which he talked about how she’d live “an uncommon life.” He didn’t say directly what that meant, and he had no idea the reality she was mulling, but through personal revelation, this cracked open the possibility that perhaps she would be able to marry someone she loved while “doing all the things I find most important and affirming regarding my relationship with God and participating in a faith community. Maybe none of that had to change.” She says, “That’s when I decided to pursue this option and try to find someone willing to do it with me. I was hoping that person might be Liz, but I didn’t express that yet.”

After returning to BYU from her mission, Liz also planned to stay closeted but admits she had “holy envy for Ryan’s plan because it sounded like such a better plan than the trajectory I was on. I felt a lot of depression and hopelessness deconstructing my faith because I didn’t see a future that was truly happy for me. I’ve always known I was meant to fall in love with a life companion, share my life, be a mother… things that didn’t feel possible to me with a man. It was tough at that point, so I was grateful to ultimately get guidance from Heavenly Father the other way.”

The two remained just friends for about a year, respecting Liz’s process and the BYU Honor Code they’d each signed, until the combination of COVID and botched travel plans placed them both in quarantine together. Liz had just flown to Washington DC to present at a teaching conference when she landed and learned the world had essentially shut down. She spent the next five days alone, reflecting on how unsettled she’d felt about not dating women when she knew where her attractions lied. Considering the “divine plan” intended for her, that week she even wrote a 30-page letter in her journal to her Heavenly Parents to weigh her options. By the end of the week, she felt she had a strong answer she was supposed to be with Ryan and that she could do a lot of good in the world if in that companionship. Liz returned a week later to Provo which had become a ghost town. The rest of their roommates had returned home, leaving Liz and Ryan to spend time together and the freedom to openly express their love. When Liz shared her feelings, Ryan says, “I don’t think I‘ve ever been so happy in my life.”

Ryan graduated that spring, and Liz had one more year that proved a roller coaster for many for LGBT students with the fluctuating “bait and switch” BYU Honor Code regulations regarding public displays of affection and dating allowances. Both women felt the frustration of feeling they had no say in how they were able to live their lives. For Ryan, this felt like the 2015 exclusion policy then 2019 reversal, but in reverse. “It caused so much damage to begin with and a lot of fear for people as a lot had started to come out and be open, then they had to go back into the closet in fear.” Like many, transferring schools wasn’t a realistic option for the women so close to graduation, with the added reality that many of their religious credits wouldn’t transfer at all.

But as quarantine became a defining factor of 2020, both Liz and Ryan say they benefited greatly from home church where they could think about what their identities meant in relation to the Plan of Salvation as they fully came out to their families and many of their loved ones.

After Liz graduated from BYU in April of 2021, she came out publicly, then drove home to Washington. Two weeks after coming out online, Liz posted she and Ryan were dating, then two weeks later, posted they were engaged. Although Ryan had been showing up in her Instagram feed since 2016, the announcements created some whiplash for Washington ward members who had known Liz since she was in diapers. One said, “I didn’t know Liz was gay or dating or engaged, then suddenly, she was getting married.” As they’ve been more public with their relationship, responses have run the gamut from one relative writing them a letter expressing disappointment that Ryan and Liz had “decided to let go of the rock of the gospel” and that they “would never find peace on this path,” to another relative holding a family intervention behind their back to decide “how to handle the situation.” Attending Ryan’s family ward alongside her family as well as the Instagram trend of “Ask me anything” presented opportunities for the women to publicly share their continued beliefs and why they were choosing to stay in the church. They appreciate when people ask them directly, rather than talk around or about them in ward councils.

The Giles have attended two wards since their marriage a little over two years ago. Of their Houston, Texas congregation, they say, “The people overall were welcoming to us, but most of them never talked about our queerness. It was the elephant in the room they never discussed, but they loved us. In Washington, people acknowledge the wholeness of who we are but it’s more complex—some keep us at arm’s length while others noticeably honor the intersectionality of us being here.” When they left Texas, they were touched when an older woman in the ward threw them a big, fancy going away party that was even announced over the pulpit. Attendees included their bishop and stake president. They appreciated these gestures after they had to carve out their own callings as the “go-to service people,” feeding the missionaries every other week and helping with lots of service projects. This was after their bishop mentioned he'd find a calling for them but never did, besides a ministering assignment. While they have not been sent to a disciplinary council or had their membership records removed, as was the case recently for a gay married couple they’re friends with, their leaders in Washington have reminded them they can’t partake of the sacrament, give talks, bear their testimonies, or have callings on the roster. But they haven’t been told they can’t participate in lessons, so they do that, and Ryan is relearning how to play the piano because she heard their Primary often needs a pianist and she wants to be ready—just in case.

Many in their current ward knew Liz growing up. She says, “One of my former Young Women’s leaders made our wedding cake. The Primary and Relief Society presidents have really stood in for the Savior for us, too, advocating so we can participate as much as we can. It’s so comforting because even though we don’t have a voice at those tables… they are making an attempt for us and telling the ward council we want to be here and serve and be members of this community.” She continues, “As a queer member, it’s really painful being seen as less faithful or more sinful to some. Seeing we’re married, some discount our testimonies or how we can build Zion. As someone who’s just trying to live her most authentic life and follow the Savior, it's hard to see how people treated me then versus now. Even though my beliefs are deeper and I’m so much happier, and in a position to do so much more good, I’m seen somehow as weaker or as an apostate by some. It’s hurtful.”

Of their newfound online following, the Giles have been overwhelmed by how many people have reached out from places spanning from West Africa to Australia to Utah, sharing similar desires and experiences of trying to find their place. They also recognize that while they’ve been able to find a somewhat safe space to occupy at church for now, that could change, and they express that their path is not always the best option for others. There are days when Ryan recognizes, “Going to church might not keep me close to God today; maybe today we go to the mountains instead.” Ryan adds, “We’re showing up because we want to be closer to Christ and connect with our community. If we accomplish nothing else externally (knowing that internally, we do accomplish more) other than showing that LGBTQ+ people do want to be there to stay connected and desire to be Christlike and closer to our Heavenly Parents, I hope that us continuing to go helps people see that.”

THE SMITH FAMILY

For 20-year-old Kyle Smith, life’s a journey—and quite literally, as right now he’s culminating eight months of adventure spent working in Alaska and backpacking through Europe, before taking a month-long cruise through Hawaii and Polynesia with his boyfriend, Ethan. The sense of freedom he now feels seems apropos for a high achieving young man who earned it, after excelling during four years of varsity soccer and his state-champion show choir as a teen, while also being elected his high school student government’s head boy and earning a 4.0 GPA. But discoveries and admissions along the way did result in misunderstandings and challenges in Kyle’s church community and even among his loved ones, that thankfully, with the support of his family, he was largely able to overcome…

For 20-year-old Kyle Smith, life’s a journey—and quite literally, as right now he’s culminating eight months of adventure spent working in Alaska and backpacking through Europe, before taking a month-long cruise through Hawaii and Polynesia with his boyfriend, Ethan. The sense of freedom he now feels seems apropos for a high achieving young man who earned it, after excelling during four years of varsity soccer and his state-champion show choir as a teen, while also being elected his high school student government’s head boy and earning a 4.0 GPA. But discoveries and admissions along the way did result in misunderstandings and challenges in Kyle’s church community and even among his loved ones, that thankfully, with the support of his family, he was largely able to overcome.

Back at home, receiving virtual postcards of his adventures, awaits the Smith family (mom Ashley, dad David, sister Hannah and her husband Matt Herron and their children, and brothers Jamison—25, Spencer—23, Cedric—16, and Levi—13), who just four years prior had undergone quite a transition. Just as David was being released as bishop—ironically being told that “someone in the ward needed some things addressed that might go better if he wasn’t bishop,” Ashley had just completed a victorious campaign and was elected mayor of their Cañon City, Colorado town, after serving four years on city council. Over the years of serving and campaigning in the community, she had been struck by how many wonderful LGBTQ+ citizens she’d met who, despite what she’d been taught while being raised in a conservative religious climate, seemed to want the same things as her family. It was at this time, at age 16, that Kyle told his parents something he’d known since age 11.

Ashley now laughs how she’d unassumingly made Kyle a rainbow cake with eight layers of colors for his eighth birthday, not knowing the significance that symbol would later take. As Kyle sat in primary as a child, he’d hear that everyone is a child of God and loved, while knowing he was different and didn’t seemingly fit the mold of what an “acceptable” child of God was “supposed” to be. In high school, he finally opened up to Ashley and David saying, “I just can’t keep getting hurt so much; I need you to know where I’m at.” His parents had watched him shun recent pressures from friends to get a girlfriend, saying things like, “I just want to be friends with everybody!” But at 16, Kyle was ready to tell his family he was gay, after which he subsequently broke down and asked, “Am I destined for a life of misery and grief?” This launched a re-examination into what his parents had been taught and taught themselves for many years. When Ashley told Kyle’s two youngest brothers Kyle was gay, she said the look on their faces was as if he’d been killed in an accident. “I thought, ohmygosh, what kind of hole have we dug for ourselves?”

This was the launch of many conversations for the Smith family. Ashley says the first two years were messy. It was not like a like switch of understanding instantly turned on, but rather a slow process of searching for understanding. She credits Kyle’s patience, saying, “He was really gracious and said, ‘I know this is the culture you were raised in, but I can see you are making an effort and trying’.” The Smiths are grateful Kyle also made efforts and they still have a close relationship. Ashley and David’s children and several immediate family members have also embraced Kyle. But many did not.

When the Smiths first approached their bishop at the time with Kyle’s news, he firmly responded that “the world” will tell them it’s okay for Kyle to be gay, but that it actually wasn’t. “That was NOT helpful,” says Ashley. A few years later, the same bishop said he thought the ward “handled Kyle’s coming out pretty well.” While allowing the bishop the same grace Kyle offered them, Ashley felt that perhaps it would have been better for the bishop to have replaced the discomfort of that conversation with curiosity. A more useful conversation would have been to instead ask questions like, “How has this affected your life? What do you wish people understood? What would you like us to know?” Luckily, their stake president was more understanding and shared his belief that Kyle could be gay and still be a happy person and even a productive member of the church.

The first Sunday after Kyle came out publicly, the whole family was very nervous about attending church. But a Sunday School teacher came right up and gave him the biggest hug, which brought some relief. So did the pandemic shortly after, as home church became the norm. Kyle found he appreciated the reprieve and Ashley says she likewise loved feeling like she could experience church “without getting stabbed in the heart. It gave us time do our own healing in home church. Kyle never went back after that.” Even pulling into a church parking lot to play a game of basketball now gives Kyle PTSD reminiscing the many times he’d come home from church or seminary and declare to his parents, “Well, I was told I’m going to hell again today.” While all of the other Smith children still attend church and several have or are currently serving missions, Kyle feels closest to God in nature. His first summer spent working in Alaska as a zip line guide gave him a lot of time hiking in the mountains with wildlife, “a chance to heal.” He’s now dating Ethan, a young man he met while working at Breckenridge. Ethan was also raised in the LDS faith in Utah, and the Smiths love that both families “just get it” with their commonalities and support their sons’ union.

Living in a rural community, Ashley says they’ve felt like they’ve been pushed to the outskirts even by some close friends, “not fitting that tribe anymore.” She currently serves as a Primary teacher which she loves, calling the kids “her happiest constituents.” Ashley’s stake president made it very clear that her main calling was to be her tenure as mayor, a role she feels God also called her for and has given her a voice to broader audiences. After the article she wrote in a 2021 issue of LDS Living about what to say when a loved one comes out as gay was published, Ashley had people reach out hoping they hadn’t played a role in alienating her family (which they didn’t). Some were grateful to find better words to start conversations, and other church members either further distanced themselves or pushed back with even more open prejudice. In the end, friendships have been lost.

Ashley says, “I don’t feel we’re in that warm, fuzzy, cozy circle anymore, but we’re there because we believe in Christ, our kids need to have a relationship with God, and we need consistent reminders of all the things that help us become good human beings.” She recognizes that things are different based on where you live and when recently asked to give a presentation to a stake Relief Society gathering in Denver about their journey, Ashley was pleasantly surprised to learn of an openly gay member of a bishopric in the area. Grateful for the resources she was able to turn to when Kyle first came out, Ashley now tries to point others to the same as well as be a resource herself, with her article and also having been interviewed on both Richard Ostler’s podcast and Kurt Francom’s Leading Saints podcast.

Four years later, David says, “I like the person I am so much more now.” Ashley concurs, “I am so grateful to have a gay son… I’ve experienced a lot of spiritually profound experiences from God. I’ve found peace in not knowing everything and just having a foundation of Jesus Christ.” As a member of many civic committees for different issues in which she tries to make voices from all sides heard, Ashley prioritizes “having resiliency, especially while watching all that’s going on in the country (politically, socially and within schools and church walls)… including contentious school board meetings with people fighting against the supposed ‘satanic evils of those grooming children to be LGBTQ’.” Ashley just wants a world where one can have a gay kid who can go to school to learn math and reading, not be bullied, and live their best life. While she is not running for another term, Ashley believes, “We still need to have forces for positive change and leaders to challenge old assumptions and prejudices.

Of her own journey, Ashley loves how being Kyle’s mother has taught her to “double check my assumptions, and have more compassion as I listen to other stories and seek to understand on many levels.” She frequently reflects on a quote from Darius Gray, a prominent Black member of the church who headed the Genesis group of the 1970s, which has largely been credited as being instrumental in the reversal of the priesthood exclusion policy. Darius said, “If we endeavored to truly hear form those we consider as ‘the other,’ and our honest focus was to let them share of their lives, histories, their families, their hopes and their pains, not only would we gain a greater understanding, but this practice would go a long way toward healing wounds.” Ashley reflects, “This is a mantra I hold to now, as I try to be more open to hearing and understanding those who are different from me. When I do this, I realize we have a lot in common.”

The Ence Family

In February of 2020, Andrew and Tiffany Ence of Stansbury Park, UT were preparing for a trip to Italy, where Andrew had served a mission for the LDS church. It was the first time they’d be leaving their three kids (Winter—now 20, Matthew—17, and AJ-13) for an extended period. Tiffany went downstairs one Sunday morning to see if they were ready for church, and to talk to her oldest about expectations while they were gone. Winter started crying and said, “I don’t want to go to church.” Then and there, Winter dropped the bombshell that they were bisexual. Winter begged Tiffany not to tell Andrew. Tiffany reassured Winter their dad would be more understanding than they thought, while silently fearing what Andrew might actually say about the situation. She delayed the conversation, but a few days before their flight to Italy, Andrew told his wife he’d seen a text on Winter’s phone that she should be aware of. Responding to a girl who’d texted, Winter replied, “I feel like I need to tell you—I know you like me, but I’m bisexual.” Tiffany looked at her husband with trepidation and said, “What do you think?” Andrew’s reply was a massive relief: “We just need to love him.” (Winter, who is nonbinary, now prefers they/them pronouns)…

In February of 2020, Andrew and Tiffany Ence of Stansbury Park, UT were preparing for a trip to Italy, where Andrew had served a mission for the LDS church. It was the first time they’d be leaving their three kids (Winter—now 20, Matthew—17, and AJ-13) for an extended period. Tiffany went downstairs one Sunday morning to see if they were ready for church, and to talk to her oldest about expectations while they were gone. Winter started crying and said, “I don’t want to go to church.” Then and there, Winter dropped the bombshell that they were bisexual. Winter begged Tiffany not to tell Andrew. Tiffany reassured Winter their dad would be more understanding than they thought, while silently fearing what Andrew might actually say about the situation. She delayed the conversation, but a few days before their flight to Italy, Andrew told his wife he’d seen a text on Winter’s phone that she should be aware of. Responding to a girl who’d texted, Winter replied, “I feel like I need to tell you—I know you like me, but I’m bisexual.” Tiffany looked at her husband with trepidation and said, “What do you think?” Andrew’s reply was a massive relief: “We just need to love him.” (Winter, who is nonbinary, now prefers they/them pronouns.)

Unsure of what their next steps should be, Tiffany simply asked Winter, who was 16 at the time, to wait until they turned 18 to fully express their true self. She was terrified of what the response would be from their very conservative community. She says, “A lot of that had to do with our impression of how the church would respond.”

Then the pandemic happened, and the whole world shut down.

Winter was an essential worker as a cashier at a grocery store and struggled having to deal with difficult people at work all day, then come home and only be with their family, no friends. They fell into a depression. It was around this time that Winter came out as pansexual, saying “I love everyone,” and changed their name from the birth name they’d been called for 17 years to their preferred name, Winter. Andrew says, “As much as I said previously ‘Let’s just love him,’ I found myself pushing back on this, thinking how hard it would be, personally, to make those changes. We argued with each other and against each other as a couple.” Tiffany concurs, “It took us awhile to realize we were overreacting.” But it was hard for them to hear the phrase “dead name” be used to identify what they prefer to call the “birth name” they’d given Winter. Tiffany says, “All our kids have family names. When you say ‘dead name,’ you’re talking about the name of my Grandpa William.” It took Tiffany and Andrew some time to understand that Winter didn’t feel the same way about the name.

Tiffany now laughs when she hears people talk about how wonderful home church was during the pandemic. “For us, it was not fun. It was like pulling teeth, it was so hard to get our kids together.” Tiffany found herself inwardly struggling as well, unsure of whether she could support the church anymore, feeling that the church didn’t support her child. Tiffany had been raised by parents who she felt never chose her—her mom was a recovering addict, and her dad died by suicide. “When I became a mother, I knew I would always choose my children, no matter what,” she says. Andrew, too, was wondering if he needed to put some distance between himself and the church. It was at this time, in the fall of 2020, that Andrew got called into a new bishopric. Tiffany says, “I felt like that was Jesus grabbing the back of my shirt and saying, ‘Nope, we’re going to keep you here’.” Andrew, too, was comforted by the bishop saying he was aware of what the Ences were going through at home and thought they would have valuable experiences to share. These feelings were confirmed quickly by multiple friends and neighbors who were also experiencing similar challenges.

Andrew recalls Winter’s last couple years of high school being rough, with them starting to push back on the typical rules parents place on teens. It felt like every weekend was a battle with Winter. Sundays during this time just didn’t rejuvenate them the way they once had. Andrew remembers one such Sunday during this time, where a friend on the high council greeted him and asked about his weekend. The friend saw through Andrew’s, “It’s fine,” response and recommended a Liahona article that had come out a year before in July of 2020 called “You Love, He Saves” by Krista Rogers Mortensen.

Andrew and Tiffany say that article changed everything for them. They’d go on their nightly walks and talk about all they were experiencing and that they were in agreement of what to do but unsure how to do it. That article taught the concept that their only duty as parents was to love their children; it’s Christ the Savior who saves. Andrew says, “It changed our perspective. We didn’t have to stress anymore over them going or not going to church. We could just be in the right place to show love. That’s what has driven us since.”

In her work life, Tiffany started to wear rainbow pins on her lanyard at the charter school where she taught, indicating she was a safe space. She freely shared her experiences about Winter to her coworkers. After hearing some troubling comments about LGBTQ+ kids from teachers at her school, she asked if she could give a ten-minute presentation at a staff meeting to educate others about the trans and nonbinary community and preferred pronouns, and the importance of being open to just listening and not inserting your religious or political opinions. This opened a lot of conversations she feels have been productive. One coworker, whose child had just come out as trans, was struggling because her husband had responded with an, “I will choose my temple recommend first.” The friend asked if the couples could go to dinner, and Tiffany’s friend was so relieved that Andrew was able to speak to her husband about how he had been processing everything in a more supportive way. The husband was able to learn what the Ences had learned – he just needed to love his child.

Tiffany now teaches first grade in a public school, and feels she has to be more subtle about her advocacy, but she still wears rainbow earrings and hair clips. Tiffany feels, “If you can’t be a safe space for all, that’s a sad thing as an educator. By all means, send those kids to me. Like if a kid has disabilities, you wouldn’t say, ‘That person just needs to learn how to talk or walk differently.’ Why would you make any negative comments about anyone on the margins?” As her county has lost more than a few LGBTQ+ kids to suicide, Tiffany feels strongly about speaking out and would love to turn that into a career.

Tiffany and some friends went to a presentation Ben Schilaty did at a library, and afterward, asked Ben if he’d come speak to their stake. He said he would as long as their stake president was on board. Tiffany feared it would be a flat out no from the stake president, but was surprised when he considered the prospect, saying in the seven years he had been in his role, no one had ever approached him about having a presentation like this before. After thinking about it, he said he’d like to start by having the Ences be the ones to share their experiences with the high council to gauge their feelings on the topic. The high council agreed, and the next step was for the Ences to present their story with the stake leadership at large. Right before this plan was executed, the stake presidency was released, and a new stake president was called. Tiffany approached the new stake president a couple months ago to ask whether he was aware of the plan and was told to send an email. Every time he sees her, he says, “Waiting for your email, Sister Ence.” She still feels it’s an important endeavor to help educate people so families like theirs don’t feel alone the way they have, but hesitates at the process of putting herself out there, knowing the opposition she may encounter: “Even me five years ago would have judged me, ‘Well, she must not have been doing this with her kids…’ I used to think that way, too, but I’ve learned a lot.”

Reflecting on when Winter first came out, Tiffany says her mama bear heart just wanted to protect them. Winter had a few negative experiences at church and with a seminary teacher who said something, which led to them walking away. “They feel like an enemy of the church, that they are not wanted there.” But both Winter and their partner Jo, have expressed support of Tiffany and Andrew’s efforts to share their story and be there for others. Andrew has worn an “I’ll Walk With You” CTR-shaped pin every week to church for the last two years. When he was asked to remove it once after the bishop received complaints, Andrew responded, “If this is sparking conversation, then that’s a good thing.” The Ences’ younger two sons have also stopped attending church. They say, “Sometimes we feel like we’ve failed as LDS parents; but we’re just going to love our kids.” A friend at church once told Tiffany, “Don’t worry, someday we’re going to get a letter in the mail about Winter’s mission call.” Tiffany says she thought, “You can live in that fantasy world, but I’m choosing to love my kid. I’ll support them whether this is a phase or not. I just hope they can look back and know ‘my parents loved me’.”

Andrew and Tiffany say Winter has always been a loving and loyal child who stands up for what they believe. When they were in elementary school, the Ences got a call that Winter had gotten into a playground brawl because a kid was making fun of their cousin. Andrew says, “I know it’s one of those experiences where I’m supposed to be upset, but I was so proud of Winter standing up for their cousin.” After school, Winter’s uncle rewarded them with a Gamestop run. Musically inclined, Winter’s fourth grade teacher taught them the viola which expanded when a middle school band teacher encouraged Winter to also learn the clarinet, saxophone, guitar, and banjo. Winter always had an easy time making friends, and Tiffany wonders if this is what made them first identify as pansexual, feeling they wanted to love everyone across the LGBTQ+ friend group in which they identified.

The Ences recently attended the Gather conference and appreciated meeting other people who are in their same boat, and not just on social media. They were especially touched by Bree Borrowman’s presentation about what it takes to look in the mirror and get to a place where you like what you see. Andrew says, “To hear Bree’s experience and then to see the challenges the world puts on people just trying to do that. They are just trying to be happy within themselves. Four or five years ago, I might have thought that was silly, but now, I get it.”

Reflecting on their experience and progress, Andrew and Tiffany say, “We think we understand the path and game we’re playing of ‘holding to the rod.’ But there are still potholes that come. You can still twist your ankle. We may have felt that the church couldn’t support us in our choice to love our child and who they are becoming; but now, we see our experiences have value and a purpose and that’s why we’re here. That we as parents in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints will love our children through the challenges and changes.”

THE JEAN & ALLISON MACKAY STORY

At 16, Jean MacKay is already an accomplished pianist, singer, and composer. He’s also a stage actor who played Mr. Macafee in Bye, Bye Birdie as well as the challenging role of Man in Chair in The Drowsy Chaperone. A serious academic, Jean has been taking college courses through ASU, and will graduate early from high school later this year. Intrigued by the bio-medical side of psychology, Jean hopes to become a forensic psychiatrist and study how various substances affect the brain to hopefully help rehabilitate people who have gone through the criminal justice system...

At 16, Jean MacKay is already an accomplished pianist, singer, and composer. He’s also a stage actor who played Mr. Macafee in Bye, Bye Birdie as well as the challenging role of Man in Chair in The Drowsy Chaperone. A serious academic, Jean has been taking college courses through ASU, and will graduate early from high school later this year. Intrigued by the bio-medical side of psychology, Jean hopes to become a forensic psychiatrist and study how various substances affect the brain to hopefully help rehabilitate people who have gone through the criminal justice system.

Considering all these remarkable attributes, Jean (he/him) says he becomes frustrated with often being reduced to his identity as a trans person. “That’s a facet of me, but it’s not all of me. It’s okay to celebrate one’s identity—that’s fun, but try to see the person before you see the label.”

Jean grew up in a family that moved around a lot. When asked about his home life as the oldest of six kids who homeschool, he smirks, “There’s a lot of screaming.” An early childhood illness kept Jean out of the first grade for an extended time, and he realized he preferred doing school independently. This kickstarted his online/charter educational path. As the MacKays would move for his father’s job, Jean says he often felt like an outsider navigating the social hierarchy of places like Utah and southern California, where his family now resides. But he says while his social development has perhaps been stunted, charter school has been worth the tradeoff.

For Jean, being trans was “never really a thing for me—I always just thought, ‘I’m a person’.” Jean first heard the word “trans” at age 10. When he looked it up, he thought, “Oh yeah, that’s me,” then didn’t think about it for awhile. Jean’s mother, Allison, said that even as a young child, Jean never gravitated toward baby dolls and playing house like their other children assigned female at birth. He always preferred to dress up like characters like Lightning McQueen, Indiana Jones, or Anikan and play with a Mickey Mouse doll. “He was never on the path of ‘I’m going to be a parent someday’.” But it wasn’t until puberty that Jean began to feel very uncomfortable in his body. Allison says that first he came out as aromantic, then nonbinary, then queer. “It’s a process. He’s still in process. I’m trying to hold space and be open for that to happen.” In the meantime, she marvels at his academic interests and ambition that so strongly juxtapose what she was most interested in at that age: “I was having way too much fun to want to graduate early,” she laughs.

Allison says that each time a new aspect of Jean’s identity comes up, like when he decided to change his name, she’s gone into her prayer closet and pleaded, “Show me how I can relate to this and understand. And every time I’m shown—oh yeah, this was always that way. I just imposed my belief system onto it. Or I just never thought of it that way, but it is true.” Allison says she’s now able to better navigate a journey of endless possibilities “because we let them be.” When Jean was younger, he cut off his really long hair to donate it to a foundation for leukemia. A few years ago, he chose to do the same; and this time for Allison, it felt like an important milestone, like, “I’m never going back to that little girl; I’m leaving her behind. It felt like layer after layer of cultural and familial expectations were removed.”

Many members of the MacKay’s extended family first expressed that calling Jean by Jean seemed to come out of left field. But Allison would clarify, “No, Jean’s been doing this since he was eight. Jean’s always had issues with clothes. Now, he has his own style and everyone comments how much they love how Jean dresses.” She’s grateful he’s shed the black, baggy clothes that seemed to characterize his mood for awhile.

Jean says, “I used to be part of a church that was not necessarily accepting of people like me, and I didn’t like what puberty was doing to my body. Those two things made me spiral, and I was pretty depressed for about a year.” Now Jean is more comfortable expressing his identity as both trans and asexual. He says when his parents first gave him the traditional “sex talk,” he thought, “Yeah, I never want to do that.” Being asexual while being raised in the LDS church environment was “not the worst thing in the world because with the law of chastity, people were constantly telling you, ‘Don’t do this’,” says Jean. “But what bothered me was the expectation I had to get married and be a mother and have kids. Most of the stuff they taught focused on marriage and family, which are not bad things, but they’re not for me. This expectation was frustrating—I felt like I was being diminished. To have my worth identified by things I don’t identify with was not interesting to me.” Jean says the things that interest him most in life—career and music—are what he wishes to be the most identifying parts of his life.

Allison embraces a set of beliefs and practices about the divine feminine and Godhead that differentiate her from many mainstream members of the LDS faith. Being verbal about this as well as some aspects of church history that troubled her led to her excommunication several years ago, which she now sees as a blessing because it gave Jean a safer place to land at home when he made it obvious the church didn’t work for him. “Jean saw me going through that process publicly, and it allowed him to have a safer space to talk about it at home. So in some ways, I see how the experience I went through made it safer for Jean to leave – and I would take the flack for anyone needing to do that. Because there were months we didn’t know if Jean was going to be able to stay here (on earth), if I can even make that one thing easier, then that’s ok.”

Allison was raised in a traditional LDS home and has learned unique lessons with raising each of her kids. But regarding Jean, she says, “I’m so grateful God would soften my heart to this child so that he could teach me who he is, and open this sphere of possibilities of who we are as humans, because before, I wouldn’t look. I was just doing and believing what I was told. I wouldn’t look and ask for myself. That was so wrong. I am so grateful Jean was courageous enough to show me that, and preserve our relationship. And I know Jean will teach me so much for the rest of my life.”

Jean’s father and some of his siblings still attend church, and Jean himself was expected to go until age 14 when the family realized it was in no one’s best interests to mandate that anymore. He had struggled to connect with many of the church milestones over the years, including at age 11, going to the St. Louis temple for the first time with his dad, which was not quite the experience he had anticipated it would be. But Jean says, “The thing that broke my shelf was going to seminary. I got it into my head that I could tear down all the things in my head by tearing down my seminary teachers and their classes. But I realized trying to tear down a religion by mercilessly tormenting seminary teachers isn’t going to help—or produce anything besides tormented seminary teachers. I don’t have a problem with people being a part of the church—it’s not a bad thing; it’s just not for me.”

Nowadays, Jean says he’s in remission from any religious PTSD he may have faced, but says spirituality isn’t really a part of his life anymore. While he considers the term “atheist” as useful shorthand and lets people know he’s not really interested in those discussions, he says he’s probably more agnostic, though he doesn’t love how that term essentially “puts him on the bench, and that’s not it.” Jean says, “What does matter is the things we do in this life and how we treat others.” Jean says he’d like religious people to know that the reason so many may perceive atheists as “angry” is perhaps misguided. “They’re not angry at you, the religious person, but angry at themselves. They feel tricked. Now that they see closer to their truth, they’re frustrated by harm they faced. They’re not trying to tear down your faith nor are they possessed by the devil, but frustrated because they don’t want others to be hurt anymore, the same way they have.”

Regarding the current political landscape, Jean advises, “No amount of anti-trans legislation will stop people from being trans; but it is going to result in dead children. So if you’re really pro-family or pro-life, please stop it. We need to foster understanding. I get it, if you’re unaware of what being trans means, it can sound scary or confusing. But my advice would be to talk to trans people and see how and why they feel the way they do.”

Upon reflecting on her experience getting to raise a child as unique and special as Jean, Allison advises, “Parents, set aside what you ‘know’ and listen – our kids are such amazing teachers. They are so smart.” Allison now believes Jean’s bravery might be paving the way as one of the oldest of 40 cousins. She wonders, “How many of those kids might one day say, ‘Ok, Jean did that; I can do this.’ And how many will sleep on our couch if their parents kick them out? Those who come after Jean won’t have to be alone. Jean can shine that light.”

THE ELLSWORTH FAMILY

(Content warning: suicidal ideation)

Gina Ellsworth’s first tip-off occurred when she and her daughter Lila were leaving to go to church. Lila’s phone connected through bluetooth to Gina’s car, subsequently streaming the “Questions from the Closet” podcast episode entitled “Am I Gay?” into the quiet space of their garage. Lila quickly fumbled to shut it off. Sensing her panic, Gina didn’t press. But Lila offered that her seminary teacher had recently recommended the class listen to such podcasts to try to have an open mind and understand different perspectives—something Gina found refreshing and “pretty cool.” But when Gina soon after emailed the seminary teacher to say as much, his “not sure exactly what you’re talking about?” response revealed that perhaps Lila had discovered this podcast on her own.

(Content warning: suicidal ideation)

Gina Ellsworth’s first tip-off occurred when she and her daughter Lila were leaving to go to church. Lila’s phone connected through bluetooth to Gina’s car, subsequently streaming the “Questions from the Closet” podcast episode entitled “Am I Gay?” into the quiet space of their garage. Lila quickly fumbled to shut it off. Sensing her panic, Gina didn’t press. But Lila offered that her seminary teacher had recently recommended the class listen to such podcasts to try to have an open mind and understand different perspectives—something Gina found refreshing and “pretty cool.” But when Gina soon after emailed the seminary teacher to say as much, his “not sure exactly what you’re talking about?” response revealed that perhaps Lila had discovered this podcast on her own.

Shortly after, Gina was again in her car leaving the house when once again Lila’s phone connected to the car while Lila was up in her room. This time, another podcast episode started playing that proved Lila had a vested interest in the LGBTQ space. Gina didn’t say anything to Lila, but later brought up the incident to her husband, Matt, who reminded his wife about the times in middle school when Lila had obsessed that if she phoned or invited her female friends over too often that they might think she liked them in a “different way” – a fear they found odd. As Lila struggled with anxiety and intrusive thoughts at the time, they just assumed this was her way of worrying too much.

A few months later, Gina decided to make her and Lila’s upcoming road trip from their home in Gilbert, AZ to Salt Lake City, UT one in which they could really talk. Lila, who was 17 at the time, was being recruited to play ice hockey at the University of Utah and was excited to go meet the coaches with her mother. Gina was anticipating this alone time in the car to hopefully ease her

daughter’s mind and reassure her that she was a safe space—with whatever might need sharing. Once on the long stretch of highway, Gina told Lila she wanted to ask her something. Lila had a look of fear in her eyes but said ok. Hesitantly, Gina asked “Are you gay?”

Lila was quiet for a moment, then her face turned bright red and tears filled her eyes. She said yes. Gina immediately reached for her hand and held onto her tightly. Gina told her how much she loved her and that love would never change. Lila had just finished her junior year of high school, but had planned to wait to tell her parents until she had left home for college. Gina was relieved she finally knew the truth, but also heartbroken to know that Lila had carried this all by herself for so many years. Gina says, “She had the mentality that if she did everything perfectly with the church, this would be taken away from her.”

For the rest of the road trip, Gina and Lila were able to finally talk openly. When they got to Utah, Lila asked if they could go to Deseret Bookstore and get some books. They took turns reading Ben Schilaty’s and Charlie Bird’s first memoirs about LGBTQ inclusion. When Gina called her husband to confirm Lila’s news, he simply said, “Tell her I love her.”

The following year, Lila’s senior year, was probably her hardest, Gina says, having to deal with conflicting views as her parents and only one extended family member knew she was gay—a relative Lila said her mom could tell because, “Being sweet, she wanted me to have some support.” Lila would go to seminary and church where several peers would say things about LGBTQ+ people that “only amplified how she was feeling and made it hard for her to feel good in her own skin.” Terrified what might happen if she revealed that their comments were directed at her, Lila remained quiet. Gina was also struggling at church and in their community with things people would say, and she often deliberated whether speaking up about how she really felt would subsequently out their daughter before she was ready.

Lila asked her mother if she’d be okay with her dating, and Gina replied with support: “As long as they’re a good person and they respect you, then of course.” Matt was more quiet about things, which was sometimes perceived as a lack of support, but when he did have a heart to heart with Lila, he assured her again he loved her and was proud of who she is.

During her sophomore to senior years of high school, Lila played on the only girls’ travel hockey team from Arizona, and they achieved their goal to make it to Nationals. Gina loved going on hockey trips with her. It was a great bonding opportunity for the two of them and they had a blast together. “But then we’d come home and I’d be up all hours of the night with her as she’d curl up in the fetal position, sobbing that she’d rather be dead than gay. She was terrified people at school and church would find out who she was,” says Gina. “When we were on those trips, Lila had one focus and that was hockey. When we would come home, the reality of being gay would set in. Lila never attempted, but she was scared she’d hurt herself. Luckily, she’d reach out to me and talk about it.” On one particularly dark night right after coming home from an amazing hockey trip where Lila’s team qualified for Nationals, they were both exhausted after an especially long breakdown. Gina says, “I remember her crying and saying that she didn’t want to live anymore. That broke my heart to hear. I replied that ‘I could never be mad at you, but I would be so sad if you took your life, because I’d miss you so much’.” Lila replied, “Then I’m going to live for you this week.” Gina remembers feeling like, “That was a win. But that that’s all she felt she had to live for was so sad.”

Attending church had been hard for Lila long before her parents knew she was gay. She especially felt her dad’s pressure to go, but they had no idea they were pushing her into an unsafe space. Gina says, “It was hard to see that in a place she should feel safe, she wasn’t.” Despite the off-putting comments of peers in seminary, during her senior year, the Ellsworths were given a gift by way of Lila’s first female seminary teacher--one who was remarkably helpful and understanding. Lila’s attendance had been pretty sparse, but Gina felt she could only tell the teacher that she just wasn’t doing well and struggling with some things. The teacher was concerned and expressed love for Lila. Lila felt prompted to tell her teacher that she was gay. The teacher helped Lila by switching her scripture buddy when her first one said too many hurtful comments, and then later helped facilitate Lila being able to complete many of the assignments online so she could graduate. This same teacher invited them to attend their first ALL Are Alike Unto God LGBTQ+-affirming conference in Arizona, something the teacher also attended and supported. Gina says, “It was amazing to be in a room with that many people striving for the same thing.” Lila wasn’t out and Gina asked her how she’d feel if they ran into someone they knew, to which she replied, “At least we’ll know they're a safe person.” They loved the conference, which overlapped with their stake conference that weekend, and Gina says, “I felt the spirit and love so much more at ALL than at the stake conference, where some of the talks at the Saturday adult session put me in tears. But at ALL, we all belonged.”

Lila was accepted at the U where she now plays on the women’s hockey team along with her girlfriend, who was also on her travel team in Arizona. While her girlfriend is not religious, she has attended the YSA ward and activities a few times in Salt Lake to support Lila so she doesn’t have to show up alone. Her girlfriend recently attended the Gather Conference with Lila. She has been a huge support to Lila on this difficult journey. Gina says, “It’s amazing that Lila is able to date and feel what it’s like to love somebody, but she still battles the shame that she’s ‘acting on it.’ Trying to stay affiliated with the church has been hard for her.”

Since day one, Gina has found support through listening to the Listen, Learn and Love, Questions from the Closet, and Lift and Love podcasts, and more recently, she’s been touched that her husband has agreed to tune in here and there. This last year, he was eager to attend ALL with her and made it a priority. They’ve been able to join a quarterly parent group, where she has smiled with affection, listening to him proudly introduce them: “Hi, we’re Matt and Gina Ellsworth. We have a daughter who’s 19 and gay.” Gina is so grateful for this group where they can openly discuss their lives with people who understand both their painful and positive experiences. Too many other things have proven difficult for Gina, like most recently watching general conference where she had a hard time with some talks, but could find hope in others. Gina has also felt the need to pull back from some people to try to preserve her sense of safety and minimize the feelings that her family is being judged. “It’s hard to be in this space and explain it to those who haven’t—it’s hard to feel understood. It just feels very heavy and isolating.”

Recently, Gina has decided to pull back from attending church. “It’s been really hard going and seeing things through a different lens now. Yet, I’ve gotten so close to God because I truly feel like I don’t have anyone. Even though my husband and I are on the same journey, we deal with it differently. He still goes, saying the gospel is what keeps him strong and reckoning he can

support the church and his daughter. I feel a lot of sadness; I don’t know where Lila fits in all of it. I have the belief that when we’re done on earth, God will be gracious enough to know Lila’s heart and mine and things will work out in the end – but I have a hard time feeling it at church now.”

Gina has had unique experiences of peace at the temple where she has had strong confirmation that Lila is perfectly made just the way she is. Overall, she recognizes her daughter’s coming out as a blessing, saying, “I do feel like my love for people in this space has expanded so much because of Lila. Stepping into these spaces with conferences, parent nights, and support groups, we’ve gotten to hear all walks of life speak of their experiences. We’re better for it. I have a lot of peace about who Lila is. I wish the rest of the world could have that love and peace. The most important thing I can do is love.”

THE BRYCE AND SARA COOK STORY

Bryce Cook is a name many in this space may recognize after having stumbled upon his 2017 landmark work, which can be found at mormonlgbtquestions.com. His comprehensive essay impressively details the history and evolution of LGBT policies in the LDS church and presents the rationale for a more inclusive path forward. His personal experience, along with that of his wife Sara, as the parents of not one but two gay sons, only lends to the family’s credibility on the topic…

Bryce Cook is a name many in this space may recognize after having stumbled upon his 2017 landmark work, which can be found at mormonlgbtquestions.com. His comprehensive essay impressively details the history and evolution of LGBT policies in the LDS church and presents the rationale for a more inclusive path forward. His personal experience, along with that of his wife Sara, as the parents of not one but two gay sons, only lends to the family’s credibility on the topic.

Bryce and Sara are founding members of ALL (Arizona LDS LGBT) Friends and Family and co-directors of the annual “ALL Are Alike Unto God” conference held every April in Mesa, AZ, that has before included guest speakers such as Steve and Barb Young, Terryl and Fiona Givens, and Richard and Claudia Bushman. But when Bryce considers the parents they were two decades ago, the parents who were stunned in disbelief at their oldest son’s admission to them that he was gay, and sadly acknowledges that up to that point he was “homophobic,“ his story provides hope that all have the potential to evolve on this issue.

“Mom and Dad, I know this will come as a shock to you, but I am same-sex attracted,” were the words that first launched the Cooks on their journey. Penned in a letter by their oldest son, Trevor, who was a freshman at BYU in Provo at the time, Bryce and Sara were completely stunned. Bryce thought, “How could this be? We were a faithful Mormon family, we had regular family prayer and scripture study, we had a very loving relationship with all our six children. And how could this happen to Trevor, a young man as honest, upright and moral as any young man I knew? It just wasn’t possible!”

But as he kept reading, Bryce saw the great turmoil his son had endured for years—feelings of guilt, self-loathing, failure and shame. Bryce’s mind then clouded with the painful reality that their son had not felt he could trust his parents with this information sooner. “He wanted to bear the burden alone, to spare us the grief.” Trevor had been afraid to admit he was a “failure” as a son, to acknowledge he was “one of those awful gays” he had heard his father reference. Bryce admits that until that moment, he’d held very un-Christlike views toward gay people and had likely contributed to the silent agony his son had suffered for so long. Bryce reflects, “By the grace of God, he had not been driven to suicide, as too many gay LDS youth have.”

While the Cooks were initially shocked and saddened by their son’s news, they let him know that no matter what, they loved him. Bryce confesses that at the time, they secretly held the hope that somehow, some way, he might be able to change. “The change, however, occurred in us.” An immediate change was the Cooks’ attitudes about gay people, thanks to their deep dive study into scientific research, evolving statements by church leaders, and the numerous experiences of LDS gay men and women. Their conclusions were threefold: 1) Being gay is not a choice. 2) Sexual orientation doesn’t change. And 3) Being gay is not just about sex—any more than being heterosexual is just about sex.