lift+love family stories by autumn mcalpin

Since 2021, Lift+Love has shared hundreds of real stories from Latter-day Saint LGBTQ individuals, their families, and allies. These stories—written by Autumn McAlpin—emerged from personal interviews with each participant and were published with their express permission.

THE HOLTRY FAMILY

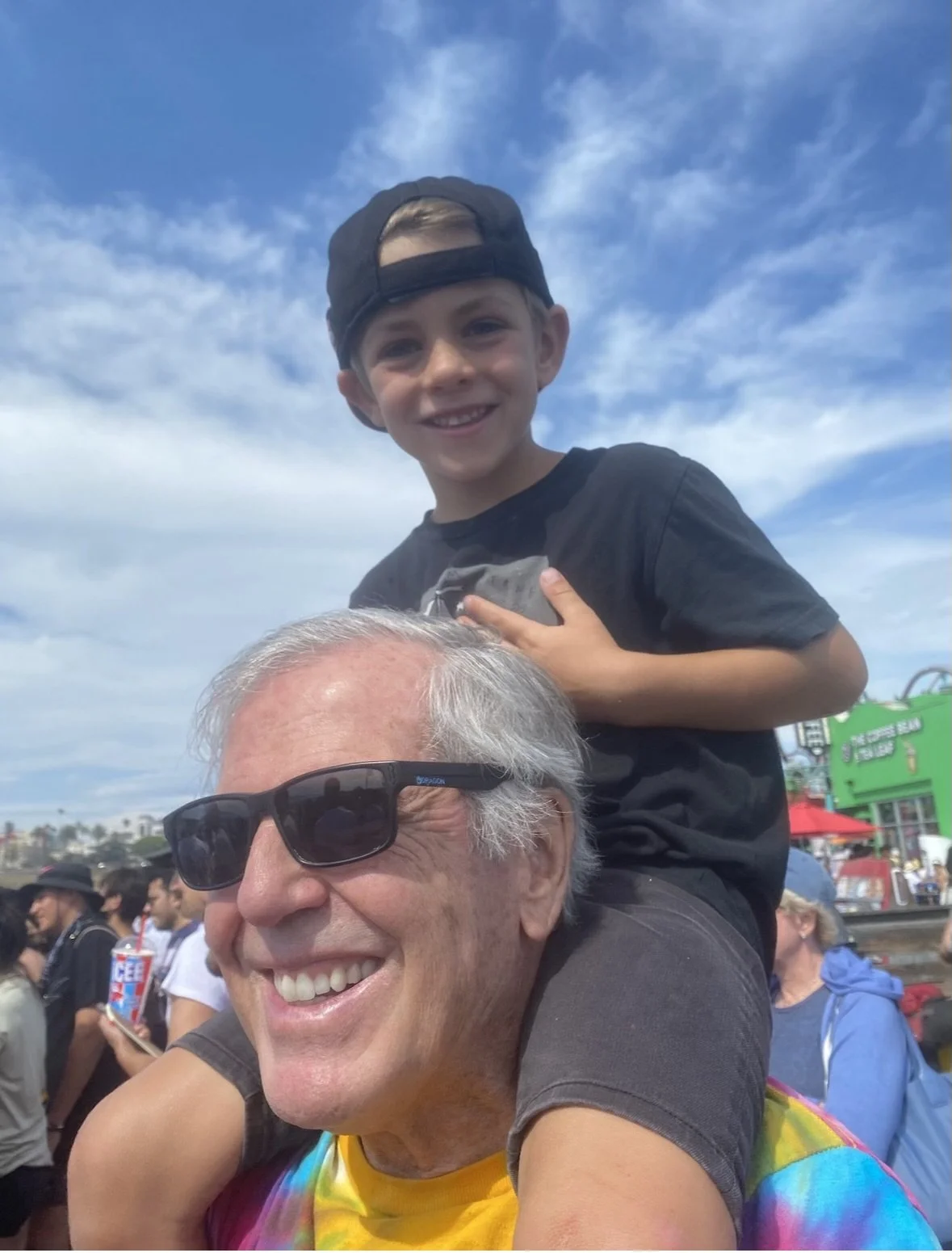

“I’ll walk with you.” It started with a sticker stating those powerful words. The sticker was given to Brent and Jen Holtry by their close friends and neighbors, Monty and Annie Skinner. Brent had been tasked with coming up with the theme for their stake youth trek adventure that summer of 2020, and he loved the concept of “I’ll walk with you.” But like most great things, what would eventually become a revolutionary trek and movement for their Fair Oaks, CA stake was not without its growing pains and delays. In hindsight, the Holtrys are grateful: they needed more time. As the year 2020 progressed, it quickly became clear that the trek was not going to happen anytime soon with the shifting guidelines of the global pandemic. This gave Brent more time to think and cull and create the needed trek plan. It also gave Brent and Jen more hallowed time at home to tend to their youngest child, Jackson, who as it turns out, would need his parents to walk alongside him that summer of 2020, when he came out.

“I’ll walk with you.” It started with a sticker stating those powerful words. The sticker was given to Brent and Jen Holtry by their close friends and neighbors, Monty and Annie Skinner. Brent had been tasked with coming up with the theme for their stake youth trek adventure that summer of 2020, and he loved the concept of “I’ll walk with you.” But like most great things, what would eventually become a revolutionary trek and movement for their Fair Oaks, CA stake was not without its growing pains and delays. In hindsight, the Holtrys are grateful: they needed more time. As the year 2020 progressed, it quickly became clear that the trek was not going to happen anytime soon with the shifting guidelines of the global pandemic. This gave Brent more time to think and cull and create the needed trek plan. It also gave Brent and Jen more hallowed time at home to tend to their youngest child, Jackson, who as it turns out, would need his parents to walk alongside him that summer of 2020, when he came out.

The Holtrys were enjoying backyard s’mores with some friends on a summer night when Jackson, who was 14 at the time, texted Jen and said, “Mom, come to my bedroom, we need to talk.” There, he told both his parents he was gay. Jen recalls they said, “Great, that’s fine, we’re supportive.” Jen had sensed this might be the case as early as when Jackson was in the seventh grade and first expressed a possible crush on a boy. At the time, Jen told him there was no need to label himself that young, and Jackson immediately said, “No, never mind.” And the conversation was forgotten. But now, Jackson knew he had his parents’ full support. He still felt worried to tell his siblings, Joshua – now 25 and in law school in Arizona and married to Lauren, and Hannah – who is now 20 and coming home from her Spanish-speaking mission to Orem, UT today (March 9, 2023). But both Joshua and Hannah were attentive to their brother and very supportive.

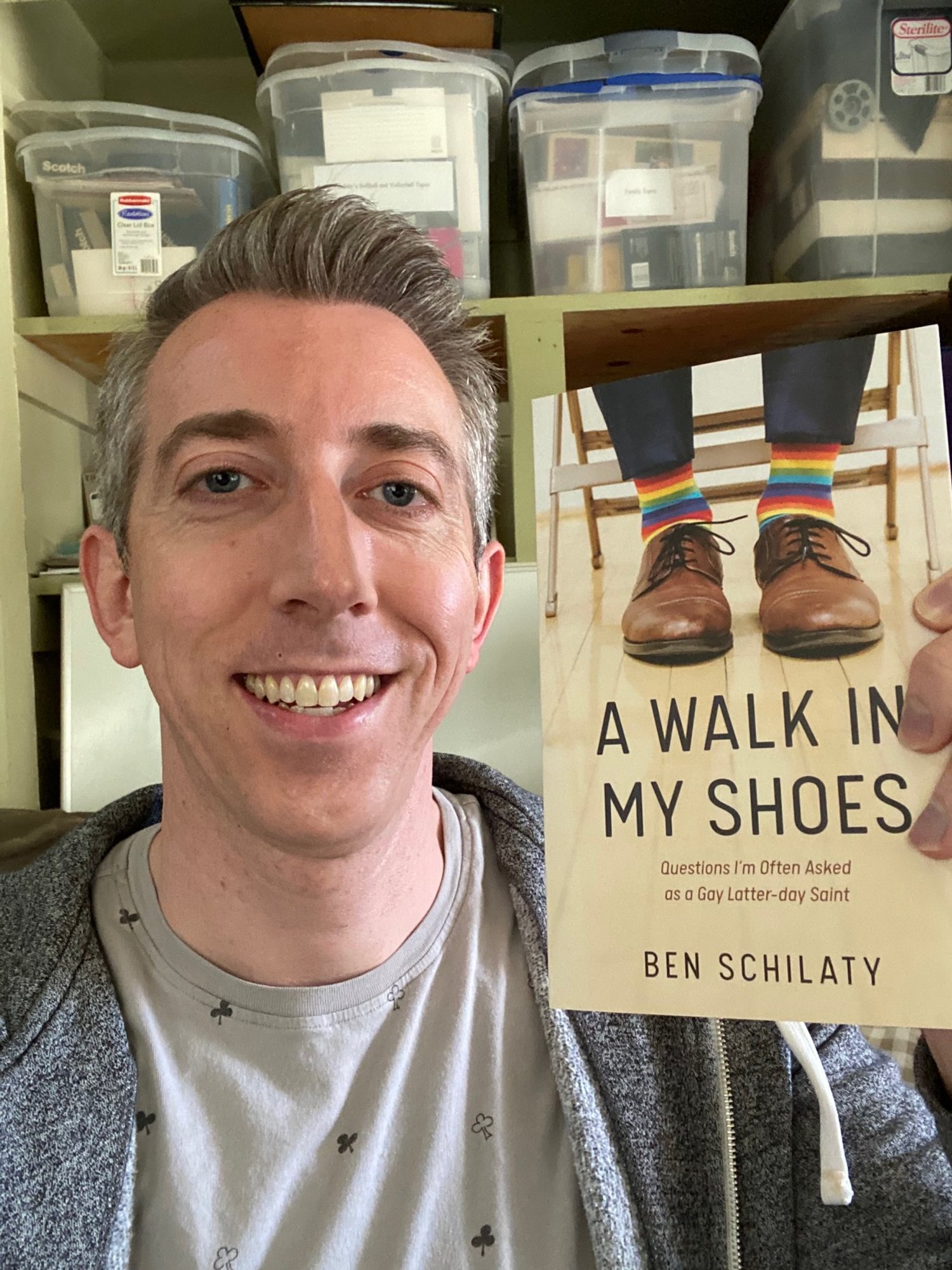

As were the Holtry’s friends, the Skinners, who had also introduced them to Richard Ostler’s podcast, Listen, Learn and Love, to Ben Schilaty’s and Charlie Bird’s podcast, Questions from the Closet, and encouraged Brent to read Charlie’s book, Without the Mask and Ben’s memoir, A Walk in My Shoes. The Holtrys had had some personal experience with gay family members prior to their own son coming out. Jen’s brother Joe had come out at age 20 when Jen’s parents were serving a mission and he had immediately left the church. That was Jen’s conception of what happened when someone is gay – that they naturally decide the church isn’t for them. So reading Charlie’s and Ben’s books opened them to a new possibility as they reconciled how to have a gay child and stay in the church themselves.

Digging into these resources opened Brent’s mind to new knowledge and ideas. He was surprised to learn that the church’s current position acknowledges that being gay isn’t a choice. He says, “Before we read those books, Jen and I were both loving and accepting but I don’t think we understood a lot of things. Before reading, I had no problem with gay people, but I didn’t like when they came out publicly. Those books helped me understand – now I welcome and celebrate when people come out.” Brent said he was filled with a desire to help LGBTQ people understand that they are loved and wanted, no matter what.

As Brent now had an extra year to consider the details of the stake youth conference and which mantra would keep the kids walking a Christlike path both on the trek and in life, he said a lightbulb went on: with statistics showing that so many youth and young adults are now leaving the church, what if there was a way they could instill a message that no matter what, they could always come back? That no matter how difficult life became, there would always be a place for them, and someone to walk alongside them, much like what the pioneers of the 1800s experienced. The Primary song “I’ll Walk with You” took on a new meaning. It all made sense.

Brent felt inspired to invite speakers to the trek who might not fit the perceived mold of an LDS congregation. As his research showed most people left the church over perceived misogyny, racism, and homophobia, he decided to invite a speaker who had been ex-communicated and later rebaptized and welcomed back into the church. He’d also invite a person of color who would not have been given the priesthood before 1978, as well as a single woman, and a gay man to speak. Jen wondered if they could possibly get Charlie or Ben to come and was shocked when Ben replied within an hour via social media that while Charlie had a conflict, he would happily join them on their trek. But Ben also mentioned that he would patiently wait until their stake approved it because while he is invited to come speak often, he is also often “disinvited” by stake leadership.

The Holtrys assumed it would be no problem for their stake to continue with this plan. Brent says he naively thought, “All would be on board with these Christlike principles of inclusion and love.” In reflection, he says he had no idea what he was walking into. His idea to invite marginalized voices to share loving messages of how they felt included in the gospel was met with fear, murmurings, and a lot of worries from the top down. Brent heard some people were complaining and even crying about the event; he heard the term “the woke trek” being thrown around with disdain. Most shocking to the Holtrys was how only one person in the stake ever addressed their concerns about a possible “agenda” to their faces – they wondered what all was being said behind their backs. But after a conversation with the stake president and his wife to dispel any fears, the leadership got on board. And once they were on board, the stake president worked hard to get the rest of the stake there. At an introductory fireside, he expressed his support for the idea, and with that, the trek, “I’ll Walk with You,” marched forward. Planning commenced, and the Holtrys were touched that Papa Ostler took the time to give them a 90-minute pep talk before the trek commenced.

And it was a beautiful experience – better than the Holtrys ever dreamed. All of the speakers came and were excellent, but one – Ben Schilaty -- stayed all three days and marched along with the kids. The Holtrys were amazed by Ben’s genuine interest in getting to know everyone, and were touched when they saw him form bonds of friendship with many – including the kids of some of the toughest adult critics.

Brent says, “After the trek, no one complained at all, about anything that had happened. Ben gave an amazing concluding fireside to the entire stake and the stake president said, ‘We have more people here than we do at stake conference.’ It was so packed, and so powerful.” Ben concluded his fireside by saying, “I don’t live here – I won’t be here every day. I’m passing the torch to you, to listen to each other’s stories.” With that wise advice, Brent and Jen, along with the Skinners, decided to start an LGBTQ support group, @learn_of_me_lgbtq.

In November of 2021, they held the inaugural “Learn of Me” LGBTQ gathering. They call it a fellowship and ally group. Jen says, “We probably have mostly allies attend, and we have had such wonderful success.” 20-30 people come and while they have not yet been able to convince their stake to advertise it, they have had a member of the stake presidency come, and a bishop has come just to check out what they’re doing. “It’s been positive. We have a 5-10 minute lesson about Christ first, and then open it up so whoever wants to can share their problems, concerns, positive things.” Sometimes they have guest speakers who are LGBTQ, and it is these meetings that Jackson, now 16, is most interested in attending.

They’ve also recently started a gathering for LGBTQ youth called S’more Love and Support Youth Hangout. The parents step out of that group, welcoming the Skinners’ daughter and her husband and a local gay couple to run it. In that circle, they invite the kids to talk and share a hurt they recently experienced. It’s been brought up that some hurts can’t be fixed, and just how hard it is to attend church. Brent and Jen acknowledge this and have told their son it’s up to him what he attends. Jen told him, “Even if you leave, you can come back. Even if you stay, you can always leave. We will support you whatever you decide.”

Jackson is now a junior in high school, and just got his driver’s license. Jen says he likes being on the swim team and “is a typical teen – he likes to hang out with friends. He has a lot of church friends, and is comfortable with a lot of kids in the ward – moreso the girls. He’s comfortable with some boys in the stake, but most of his friends are girls. At school, he has a diverse group of really nice kids, and travels from friend-to-friend group. He’s very social.” Brent laughs that he recently had an interesting conversation with a dad from their ward as they talked about the irony of allowing the other dad’s daughter to have a sleepover with Jackson and how that dad said, “I never thought I’d be advocating for my daughter to sleep over at a guy’s…” Brent says, “Everything is so different. Growing up, we told our kids. ‘When you live here, you go to church, you’re active,’ but we’ve had to rethink things.” Jen says, “I’m definitely known for speaking up now. People probably roll their eyes now when we speak. I don’t care anymore. I’m over it. I feel so much closer to Christ and my Heavenly Father -- moreso than I ever have over the past three years.”

The Holtrys have experienced love and support from friends and family, though they say they’ve learned that many want to draw a line as to what they will support. Some are less interested in hearing how the church should change policies or how leaders could be more sensitive. Brent says he’d love for leadership to understand that, “Many members are incapable of separating between loving and condoning – that message backfires, because it’s impossible to do that. What’s heard by the marginalized is they’re not accepted. That message is so very damaging. They need to know – we just love like Christ did. When people say, ‘Christ loved but didn’t condone.’ Nope, that’s not true. He just loved them.”

And in Fair Oaks, CA, that is the trek the Holtrys still walk as they invite others to “Learn of Me” and invite all into their circle where they commit to a mantra that now holds extra meaning: “I’ll walk with you.”

GRACEE PURCELL

It was fall of 2022 and Gracee Purcell had just arrived in Provo, UT to begin her first year at BYU. Not only was she excited about pressing play on life in a college town, but she was also feeling a bit safer after discovering the RaYnbow Collective—an LGBTQ+ coalition and resource provider wherein she could exhale and be herself. Their first initiative that fall was to fold and distribute 5,000 small booklets advertising LGBTQ+-friendly resources (therapists, safe housing, scholarship and event info, etc.) in the welcome bags that would be given to incoming students at New Student Orientation (NSO) with the hopes that the info would prove helpful to the (reportedly 13%) of BYU students who identify as LGBTQ+. But the day before NSO, the RaYnbow Collective received word that a unilateral decision was made against their contract with BYU and their booklets would be pulled and thrown away…

It was fall of 2022 and Gracee Purcell had just arrived in Provo, UT to begin her first year at BYU. Not only was she excited about pressing play on life in a college town, but she was also feeling a bit safer after discovering the RaYnbow Collective—an LGBTQ+ coalition and resource provider wherein she could exhale and be herself. Their first initiative that fall was to fold and distribute 5,000 small booklets advertising LGBTQ+-friendly resources (therapists, safe housing, scholarship and event info, etc.) in the welcome bags that would be given to incoming students at New Student Orientation (NSO) with the hopes that the info would prove helpful to the (reportedly 13%) of BYU students who identify as LGBTQ+. But the day before NSO, the RaYnbow Collective received word that a unilateral decision was made against their contract with BYU and their booklets would be pulled and thrown away.

Gracee says, “It was disappointing and disheartening to hear about the decision, especially when a lot of the council remembers how isolated, lonely, and unsupported they felt when starting at BYU. I know I personally felt a loss of hope. I had come to BYU hoping for a fresh start somewhere I could do more. Having this happen on day three at BYU for me was hard. I took time to process and the next day when I went to NSO, I definitely thought about the missed opportunity to support the incoming queer students.”

However, Gracee says this provided her with her “why” and a renewed passion for advocacy, especially at BYU, “as well as the realization that maybe there’s nothing wrong with us. Maybe it’s just really difficult to exist within a system that was not designed to support spirits like ours. No student should feel alone. No student should feel rejected by their university because of their identity. I chose right then that I was going to lead with love.” While Gracee says she’d rather have seen those resources end up in the NSO bags, she’s grateful for the experience it gave her. Impressive wisdom for a 19-year-old who only came out as gay to her closest friends and a few family members one year ago.

Gracee’s life thus far has likewise been rather impressive. She graduated from high school in Eagle, ID in 2021, and by that point, had already achieved her Associate’s degree from Boise State. Her father, Brandon Purcell, says she was a born leader. The oldest of six kids, Brandon says Gracee was just two when her first sibling was born and he remembers telling her she had a super power as the oldest child—that people were going to follow her. “In hindsight, that’s a lot to put on a young person. But we noticed in her toddler years, her future would be as a leader… I think one of the reasons she went to Provo was because there was an opportunity for her to both grow and lead. This year she’s found those. I see her doing a lot of fantastic, important and impactful things—not only for herself, but for others.”

After high school, Gracee spent the first semester of a gap year in Mexico teaching English part-time at a school through an International Language Program. As a first-year student at BYU, she is now a junior credit-wise, and studying Psychology with plans to become a physical therapist for athletes. Gracee’s always had a heart for helping those in need, and since the age of 15, has helped train seeing eye dogs. Throughout childhood and her high school years, Gracee’s also loved sports. She played soccer, lacrosse, and even tried pole vaulting for a season to overcome her fear of heights.

She also overcame her fear of coming out by doing so for the first time to her travel group in Mexico, six days in, which in hindsight she says was maybe not the best idea. But in a surprising turn of events, she was embraced and loved wholeheartedly by the girls in her group. She came home and went back into the closet but then started an Instagram and blog (@to_all_the_latter_day_gays) in which she shared her truth of being attracted to women. Soon after, she was invited to go on Richard Ostler’s podcast as a guest, at which point she felt it was time to tell her parents.

When she came out to her parents, Gracee says there were a lot of tears on her mom’s end. She had never considered this might be a possibility. Later that night, she came out to her dad privately and he thanked her for telling him. Brandon says he recalls thinking this was a moment with a lot of gravity and he didn’t want to say something that would come across as unsupportive or unloving. “I think I expressed something to the effect that I was grateful she had shared this with me, and I’d like to just think on it for a bit and talk about it after I’d collected my thoughts.” Gracee says she knew it would take some time for her parents to wrap their heads around everything due to their strong faith in the church. She senses their faith has always been straight forward and that this was a nuance they perhaps didn’t fully understand quite yet. But she appreciates how they listened to podcasts like Listen, Learn and Love and Questions from the Closet and read recommended books. Still, there wasn’t a lot of conversation about her orientation at home in that time before she started at BYU, and it was Gracee’s choice to not tell her younger siblings or extended family members quite yet.

Brandon concurs it took more than a minute for him to process that the future he’d envisioned for his daughter might look a little different, but that ultimately both his and his wife’s love for and hopes for their daughter to be happy and fulfilled haven’t changed one bit. Brandon hopes Gracee will “be everything she can be and have the types of connections that are important to all of us.” He appreciates the broadened experience he’s gained from listening to the experiences of others from the LGBTQ community. And he’s expressed to Gracee an impression he felt through the Spirit that while he doesn’t have all the answers to life’s complex questions, he knows one person who does. Brandon encourages his children to, “Stay close to the answers. Stay close to Heavenly Father, and He’ll guide you.”

Gracee had offers to attend other universities, but chose BYU for a particular major and to be closer to family. While she didn’t initially plan to come to BYU as such a vocal representative of the LGBTQ community, she has since realized the importance of the work that needs to be done there and is willing to be in the public eye, even under criticism, to try to create the changes necessary to make it safer for others—especially those who are not quite ready yet to be out. Gracee recognizes how important it is to find a support system and was very intentional about doing so, and thus joined the RaYnbow Collective as soon as she arrived in Provo. About 50 people serve on the council; Gracee has served as the website and design graphic design lead, and was just asked to take over as President in April.

Gracee acknowledges the climate at BYU is hard, and prospects for dating as a queer student even harder as there is always a fear that permeates. She says LGBTQ students are aware of the different messages given to different students based on who their bishop might be—there have been instances where bishops have required students self-report to the Honor Code for any attempts to date. “It’s so variable between bishops. Some are allies, some aren’t. You just have to choose what you tell them.” There’s also the constant fear that fellow students may rally against your very existence, as a group of protestors did at a Back to School Pride event held just off campus. Gracee is grateful her psychology program is filled with wonderful, supportive peers and professors.

“I think that the ultimate path forward will be with compassion and curiosity. If we move forward in that way, I think hearts and minds will be more open, and there will be more understanding. It’s not about policy change, but people changing,” says Gracee. “There’s always hope. I don’t think God should be confined to one religion or a set of practices. You can find God anywhere. I don’t think we should put God in boxes. In the end, the ultimate problem we’re having is in the core teaching of Jesus, which is to love your neighbor as yourself. The designation of who your neighbor is has nothing to do with geography or orientation or our differences, but rather with our ability to see our shared humanity.”

In high school, Gracee started training guide dogs as a strategic way she could negotiate bringing an animal into a pet-free home. She has since brought up three dogs in the program and currently has a lab puppy living and training with her in Provo. The dog attends classes and events with Gracee at BYU, and is a visible reminder to many students that some people walk through life differently. Some have different needs. And sometimes, it just takes a little training and some resources to get there. Gracee Purcell is one young adult willing to make the personal sacrifices to help others to get there. To help others to see.

BEN SCHILATY (Part 2)

After receiving his PhD in Tucson, Ben Schilaty’s path veered north, back to Utah, when he felt the timing was right to apply for the MSW program at BYU. And it was; he was accepted. While there in 2017-2018, Ben reached out to the BYU administration and said he wanted to be involved in LGBTQ causes. While initially guarded, they agreed to meet with Ben. Ultimately, BYU formed a working group of nine administrators and LGBTQ nine students who met once a week to talk about inclusion and the climate at BYU. This is where Ben met Charlie, and they became truly good friends. He also met Steve Samberg, the general counsel at BYU, who also became a good friend and set Ben apart as a High Priest…

Welcome back for part 2 of Ben Schilaty’s story. (See story posted on 2/16/23 for first half.)

After receiving his PhD in Tucson, Ben Schilaty’s path veered north, back to Utah, when he felt the timing was right to apply for the MSW program at BYU. And it was; he was accepted. While there in 2017-2018, Ben reached out to the BYU administration and said he wanted to be involved in LGBTQ causes. While initially guarded, they agreed to meet with Ben. Ultimately, BYU formed a working group of nine administrators and LGBTQ nine students who met once a week to talk about inclusion and the climate at BYU. This is where Ben met Charlie, and they became truly good friends. He also met Steve Samberg, the general counsel at BYU, who also became a good friend and set Ben apart as a High Priest.

Ben says he felt safe at BYU. In this working group, he was able to open up and have raw, emotional conversations. He felt everyone cared, and knew he wouldn’t get kicked out. One time in a meeting, Steve made a comment, saying “I’m dating myself here,” to which Ben replied, “I’m a gay BYU student, I’m only allowed to date myself.” He says the group laughed; they got it.

In 2018, the group planned a campus-wide LGBTQ forum and a few thousand people came. Ben spoke on the panel, and at the end, one of the moderators told the group, “If any of you who are LGBTQ feel comfortable standing, we’d like to recognize your presence.” Charlie had said the opening prayer at the event, and now Ben looked down and watched him stand, for the first time timidly coming out publicly. Ben says, “Charlie watched that forum and said, ‘Maybe one day I could be brave,’ and now Charlie is braver than all of us.” Ben concluded, “I don’t want to do ten things, I want to get ten people to do one thing. If I can inspire someone like Charlie to have more courage, and people to be themselves, to share their lives and hearts, then that’s success.”

And now the big question: what is it like to work at the BYU Honor Code Office as an openly gay man? Ben says, “Life is really good; things are complicated. But I’m very secure in my life. People don’t like me on many fronts, but I have a really good life. When Sunday night would roll around when I was teaching middle school Spanish, I’d dread the week. But I’ve never felt that way here at BYU. My boss especially lets me soar.” Ben also works as an adjunct professor, teaching a class called Understanding Self and Others: Diversity and Belonging.

In 2021, Ben had the idea to plan a big concert and call it BYU Belong. Kind of a LoveLoud, BYU style. Ben hoped as people came back to campus that fall, they could have a good time and celebrate their diversity. Eight video vignettes featured students and faculty who represented diverse experiences: international students, a woman of the Muslim faith, and a student grappling with mental health challenges. Each of them came up on stage after to a standing ovation. Performers included David Archuleta, Vocal Point, Charlie Bird (with the Cougarettes), and after Noteworthy performed, two of their members came out publicly. Three weeks prior, BYU had created the Office of Inclusion and Belonging, and the timing of all this at the university felt especially right and needed.

Ben says he knew LGBTQ students were afraid of the Honor Code, and he thought if he worked there, it might be less scary for them. He says, ”I love BYU, and I actually really like the Honor Code and the mission of BYU. I wanted to be a part of it. I have queer students come visit me – and on purpose, I ask them to meet me in my office so it’s less scary, and they can meet everyone. I take them to lunch. The Honor Code Director, Kevin, is the best. I find that queer kids fear the Honor Code because they don’t understand the process, who’s safe and who isn’t. But I experience no fear here in saying I’m gay because I follow the honor code.” Ben recognizes he’s speaking from a perspective of privilege. He continues, “I’m super confident and old and tall – I’m an authority figure here, which comes with safety – a freshman doesn’t have that. If someone’s unkind to me, I can call general counsel immediately and meet with dean. But the students can’t necessarily, so I understand their fear. I hope they know they have allies in the Office of Belonging and in me and many professors. Campus is a lot better than it used to be.”

Ben does occasionally field an off-putting comment or question, and he’s become known for the grace he offers back. “For example, a kid might say, ‘People are choosing to be gay because it’s cool.’ What I would say to that is, ‘Thank you for having the confidence to share that. Elder Ballard said the experience of same sex attraction is a complex reality for many people,’ or ‘According to this church leader these attractions aren’t chosen,’ and in my experience, that has been the case. I know hundreds of people who are LGBTQ, and this was not a choice for them. Having those quotes in your back pocket, and sharing your personal experience – people can’t discount that. If you share yours or your brother’s experience, at least they might walk away knowing this person didn’t choose.”

When LGBTQ families ask, is BYU safe?, Ben is in a unique position to offer perspective. “Physically, almost definitely. Will people say rude things? Totally. Can. You live in a world where people are rude? Yep, that’s the world. There are jerks. There are 30k students here, you can find your crew. There’s the Office of Belonging, and a gay man works there, and he is amazing. And there are off campus organizations that are not affiliated with BYU, but they can provide support–like USGA, Rainbow Collective, Cougar Pride.”

None of this negates the fact that it is still difficult to be an openly gay man in the LDS church, and under the public lens Ben now lives under constantly as BYU faculty and a popular public speaker and author. Most weekends, Ben can be found doing a fireside or speaking on a panel, when not producing his podcast with Charlie. During Q&A’s, many ask the obvious questions: do you think the church’s policies will change? (Likely, as they always have.) Do you think your path is for everyone facing a similar reality? (Not at all. I encourage you to get to know the stories of the LBGTQ people in your life and support them as needed.) Will love lie in your future, as it did once in your past with a man you almost left the church for? (Remains to be seen. The details of this are also in his book.)

While some may not understand how Ben does it, the path he’s forged and the trails he’s blazed to make it easier for others who might one day be taking a walk in similar shoes is rather remarkable. And in the midst of where the church sits now on this issue, Ben has found a way to be content with the in between. He says, “I live in this world where there hasn’t been resolution – the Holy Saturday – but I love living with hope. I love working in the temple weekly, I love living with my housemate Charlotte (Eugene England’s widow). I love reading scriptures. I love feeling God’s love. In the first verse of Book of Mormon – we read that Nephi feels he’s been highly favored, though he feels many afflictions. Things sometimes suck, but God is always there for me.”

BEN SCHILATY (Part 1)

At least once a week, there’s one particular professor at BYU who meets a student on campus for lunch. He’s exceptionally extroverted for an academic, and considers these lunches the highlight of his week. Over Cougar Eat confections, they discuss how to navigate life, love, and quite possibly, how to survive being gay at BYU. His is a story you may already know; his life is one most likely do not. But Ben Schilaty’s invited all to join him for a walk on his path in his memoir, A Walk in My Shoes: Questions I’m Often Asked as a Gay Latter-day Saint. Many wonder how does Ben do it? How does he live as an openly gay member of the LDS faith who not only observes the BYU Honor Code, but works within its office. But he does; and many who get to know him up close do walk away convinced he’s found a way to be content with a complex reality…

At least once a week, there’s one particular professor at BYU who meets a student on campus for lunch. He’s exceptionally extroverted for an academic, and considers these lunches the highlight of his week. Over Cougar Eat confections, they discuss how to navigate life, love, and quite possibly, how to survive being gay at BYU. His is a story you may already know; his life is one most likely do not. But Ben Schilaty’s invited all to join him for a walk on his path in his memoir, A Walk in My Shoes: Questions I’m Often Asked as a Gay Latter-day Saint. Many wonder how does Ben do it? How does he live as an openly gay member of the LDS faith who not only observes the BYU Honor Code, but works within its office. But he does; and many who get to know him up close do walk away convinced he’s found a way to be content with a complex reality.

Every week, from a fancy Provo, UT studio (aka Ben’s basement), Ben joins his friend Charlie Bird on their podcast, Questions from the Closet, to discuss the unique paths they walk as openly gay men who try to stay tethered to the church they both served missions for (Charlie in CA, Ben in Mexico), and the gospel that they love.

Ben Schilaty was the youngest of four kids born to Seattle, WA-based parents who were active--both in the LDS church and in sports. His dad was a track star, his mom was a PE coach. His older brothers were basketball stars, and his older sister played three sports. Ben laughs that he preferred to play with My Little Ponies and watch TV. He appreciates that his parents supported his interests, and he remembers getting My Little Ponies for his birthdays and Christmas, and no one in his family heckled him for it. He was a child of the 80s-90s, and he also loved hot pink, but he would get teased by others for this, so he didn’t wear many hot pink things, besides a particular pair of pink and white-striped shorts he had to retire by age five when the heckling got too loud. Ben says, “My interests were different, but I don’t remember having crushes on boys as a kid. You were supposed to have crushes on girls, so I’d say I did. I had feminine tendencies and interests, but it wasn’t until I was around 11 that I noticed I was attracted to guys.”

In middle school, Ben would admire handsome, athletic guys, and at the time, he convinced himself he wanted to look like them or be like them, not like them. He was jokingly called Ben Gay (because of the commercial), and says, “That was terrifying to me; I didn’t want anyone to think that.” He says, “In middle school, guys are typically jocks or jerks, and I didn’t fit in with either.” As a youth, Ben loved animals and, going to the zoo, and he was an organizer “builder,” and the president of many clubs including a recycling club he started in his neighborhood. His family lived near the ocean, though they could barely see it through the Seattle trees, but Ben loved exploring his surroundings and going on hikes.

In high school, Ben was convinced he was just extra good and righteous, as he watched his friends around him having chastity issues with girls, and issues with porn—things that weren’t a problem for him. He found a friend group in the “brainy kids” he’d latched onto in eighth grade, and stuck with kids who were invested in learning throughout high school. He didn’t fit in as well with the guys at church, mainly because he didn’t like playing basketball in the church gym with them, but sometimes they’d hang out and play video games.

Ben flew through his worthiness interview with his stake president to go on his mission, and served in Chihuahua, Mexico. He recalls on his mission having minor attractions to one or two guys but says, “I didn’t let myself believe it was a real thing.” After he’d been home for one day, he was watching a reality TV show with a “bunch of hot guys and it hit me. Oh no, I am attracted to guys and my mission didn’t fix it.” That first night, Ben prayed, “Heavenly Father, I’m gay, I don’t want to be. Can you fix this?”

Ben found his way to Provo, UT, the land of plenty for dating and decided he would do all he could do find a woman to fall in love with—he only needed to find one. For two years, he tried and says he “felt pretty normal. I went on tons and tons of dates.” At one point, he found a woman he liked and after going on many dates, wanted her to be his girlfriend. She came over to watch a movie on their first date and during the last ten minutes of the movie, he held her hand. He was convinced that meant she was his girlfriend, but the next day she had to correct him and say that she felt they were just really good friends. She didn’t feel a spark. Ben laments, “I wanted a girlfriend so bad for the optics, and now I didn’t have one.” In his 20s, Ben says he went on 27 blind dates, went out with at least 100 women, and had a relationship with three women. None of these resulted in a wife. Ben says, “Outside, my life looked normal. But I was praying every day, fasting every month that God would help me be attracted to the daughters of God (and not the sons of God). After a few years, I prayed I could just be attracted to one girl. I was constantly thinking, how can I fix this. But I wasn’t in turmoil, it was an okay time.”

He says he’s one of the lucky ones. Ben has no recollection of being teased or bullied for being gay, and says that largely in part of the healthy sense of confidence his parents instilled in him, he didn’t experience any anxiety or depression which would make things worse. As his prospects for temple marriage stalled out, Ben invested himself in his education and career. After graduating from BYU in Latin America Studies in 2008, Ben taught high school Spanish in Washington for a year. Then he came back to BYU for a Master’s in Spanish Linguistics minor, then after another gap year in Washington, Ben moved to Arizona to attend one of the best PhD programs in the nation for second language acquisition in and teaching at the University of Arizona.

It was in Arizona that Ben for the first time faced the reality of his orientation. He says, “I lived in denial in my teen years. At 21-22, I thought I can fix this. Then, I can’t fix this, this is going to be part of me and that’s when I got depressed. The acceptance of that was real, and led to depression and passive suicidal ideation. I thought the only way out of this was death. That went away once I finally came out and accepted myself and was accepted by others.”

Ben details his full coming out story in his book, and he says it was a moment that was so important to him, he dedicated his book to his best friend from high school and his roommate who were both there. “People need to realize if you’re one of the first someone is coming out to, you never realize how important that moment will be forever. Even though my friends didn’t know that would be a moment I’d talk about the rest of my life, they were prepared for it. People don’t know when these life changing moments are coming–we need to just love people, and take them where they’re at because these moments come out of nowhere. We need to prepare before.”

After he came out, he wasn’t too concerned about his orientation, knowing he had the support of his family and friends, but still convinced he’d find a way to marry a woman. This was the time of the viral Josh and Lolly Weed story, and Ben says that post was sent to him probably two dozen times. He even recalls going to a wedding in Seattle and running into them in the temple marriage waiting room and fangirling a little.

But Ben chose to come out on a need-to-know basis, primarily from the desire to educate others. His first year in Tucson was the worst year of his life. At age 29, he felt he did not yet have the career or family life he thought he would, he lived in a bad part of town, and “everything was bad and I thought it would stay bad.” But the following year, Ben felt compelled to come out publicly. This terrified him because he was the only Ben Schilaty on the internet, and he knew the story would follow him forever and possibly impede his then-goal to work in admin at the MTC.

“That coming out blog post shifted the entire course of my life. What happened because of that--all these people who reached out and who had been struggling. I’d been doing it alone, with no window. Once I saw how many were alone, I realized, I can’t change the world, but I can change my town. I reached out to my stake president and said I want to start a support group. He assigned a high councilman to meet with me – we planned monthly meetings. We started a group and three dozen joined. The institute director asked me to speak and 50 people came. This changed my life. Kelly Bower was on board for creating a place of inclusion. My last semester in Tucson, he pulled me in and wanted to thank me for all the work I’d done. He said a freshman had just come in to thank me for creating a safe place for people to be out and gay and active. I don’t know if people understand how important it is that leaders do those things, and create those spaces.” By the time he moved, Tucson had become Ben’s favorite place. The institute banner there now shows someone with a nose ring, people of color, and advertises that “everyone’s welcome here,” and they are. Ben says, “Tucson is not the most beautiful place, but it is to me because that was where I was able to be me for the first time – I thought, ‘This is my home. I can spend the rest of my life here’.”

But Ben didn’t. Next week, we’ll continue with part 2 of Ben’s story and follow him back to Provo where he’ll share about the work he now does as an author, speaker, BYU professor, and employee at the Honor Code Office.

THE PRIEST FAMILY

Growing up in Idaho, Gwen Priest spent more time at the racetrack with her family than at church. Her parents sometimes took her and sometimes didn’t. They sometimes drank, and sometimes didn’t. Because of this so-called “sinner” status, she felt a tension within her largely-LDS community. Some families wouldn’t let their kids play with Gwen and her siblings. But Gwen always loved the gospel teachings and the sense that when her family life wasn’t stable, the gospel was…

Growing up in Idaho, Gwen Priest spent more time at the racetrack with her family than at church. Her parents sometimes took her and sometimes didn’t. They sometimes drank, and sometimes didn’t. Because of this so-called “sinner” status, she felt a tension within her largely-LDS community. Some families wouldn’t let their kids play with Gwen and her siblings. But Gwen always loved the gospel teachings and the sense that when her family life wasn’t stable, the gospel was.

One thing she absolutely learned from her parents was that Christ loves all equally. Her family hosted foster siblings, alcoholics, the homeless and other “lost souls” on their property through her younger years. Her dad had had a rough upbringing himself and taught her, “That’s what we do as Christians. If someone needs something, you help them.”

After moving out on her own, Gwen had a successful IT career in Utah. At 21, she was single, owned two cars and loved her job. People would constantly ask if she was going to serve a mission and she’d think why? I love my life. The older she got, the more she observed church felt like a competition; and eventually, she quit going.

In 2000, she moved to New York City with a friend from Utah and decided to give the Manhattan ward a try. She walked in and saw a man wearing a dress and full make-up. In the chapel, someone pointed out someone who was gay, someone who was trans, and in the corner, a group of BYU interns who looked scared and lost. Observing the diversity in the room, Gwen finally felt, “THIS is my church. This is how it should be, anyone and everyone showing up as who they are. I felt welcome and comfortable. It saved my testimony of the church as an organization.”

Gwen got married, had her first baby, and laughed when her parents said she became a “flaming liberal.” Soon she and her young family moved to North Carolina, where one became four kids. When Gwen’s third child, Maggie, was 10 years old, Gwen found her in her room crying. Maggie had always struggled with anxiety, but this time she could hardly talk when her mom asked her what was wrong. Finally, Maggie said, “Mom, I think I like girls—am I going to hell?” Gwen says, “I had so many feelings and worries, it was like a dam opened. I immediately started praying for the right words, knowing damage can happen in those initial moments. I asked God, ‘What does my daughter need to hear’?” The answer came immediately and Gwen replied, “Of course you’re not going to hell, where did you get that idea?” Maggie shared she had “heard some things” at church. Gwen thought of a few gay friends the family had and said, “What about (this person). Do you think they are going to hell? No? Well neither are you!”

When Gwen left the room and shut the door, her first thought was that her daughter was so young, only 10 years old. She hadn’t even really started puberty yet, how could she know this? But the answer Gwen received to her prayer was, “Just trust her and listen.” Gwen told her daughter she had a lot of changes coming up with her body, friends, and school. She advised Maggie to just take one day at a time and always remember that she had a loving Heavenly Father. She just wanted her daughter to be loved and happy.

Gwen says Maggie’s effervescent, open, and loving personality drove her to want to be honest with a few close friends, even at her young age. Suddenly, Gwen observed Maggie experiencing the same thing she had as a child—other church families pulling away and ostracizing her. Someone in the ward told the Primary president to not let their daughter sit by Maggie. After getting her rage in check, Gwen spoke with the bishop and requested he be prayerful about the Primary teacher they chose for her daughter as she was still dealing with some depression and anxiety. Even with this setback, most of the ward, including the bishop, were kind and quiet about the situation, if not accepting.

Maggie’s coming out to her siblings went well. She was put in charge of a Family Home Evening night where she got up and said, “Well, everyone, I’m gay.” Her older brother and firstborn sibling, Evan—now 19, said, “What?! I’m so confused. How can a member of the church be gay?” As a family, they all talked about what this meant and the fact that Maggie was still young. Gwen told her kids, “You’re still figuring out who you are. Stay close to God, say your prayers, and hopefully we’ll all stay close so we can support each other. We just want you to be happy.”

In 2018, Gwen and the kids’ father divorced, and Gwen decided it was time to live out her dream. She packed up the kids and they set off to backpack through Europe for six weeks. A friend who had LGBTQ kids of her own joined them for part of the trip. Gwen recalls one morning in Toulouse where at 5am she was packing up the car so they could quickly leave for their next stop. While shoving everything in the tiny trunk and looking for George’s missing shoe, Wren approached Gwen and said, “Guess what… I’m gay.” Gwen had no idea how to process this information, which she needed to do on a dime as they had to quickly depart. She looked at Wren and said, “Ok, um, let’s hug. Help me load the car and can we go for a walk as soon as we get to our next stop? I don’t want you to think this isn’t important but… uh….”

Wren (they/them) had been off on their own at a study abroad language immersion program and had just met up with the family. On Wren’s study abroad, they had fallen for another girl in the program. Upon learning this breaking news, oldest brother Evan said, “What is going on? Why are all my siblings gay?”

A year later, Wren approached Gwen and said, “Actually I’ve felt for a long time I’m nonbinary and want to change my name.” Gwen says, “Of all the coming out that’s happened in our family, that was the hardest. As a mom, having raised this child from pregnancy, I didn’t realize how invested I was in their gender. In spite of how open you try to be, you still end up with these subconscious hopes and dreams for your kids. I didn’t even realize they were there until Wren sat me down that day and I had to start adjusting.” Gwen thought, “What does this mean for my baby? That was the hardest for me⎯letting go of my gender expectations for my child. I still have a lot of questions about gender identity, but I love the person Wren is growing into and I’m so proud of their resilience and strength.”

Gwen prioritized core principles throughout her children’s upbringing since they were tiny, including daily scripture study. When Come Follow Me was changed to “Come Follow Me Home” thanks to the pandemic quarantine, Gwen’s family started having tough discussions about how women were treated in the Bible, non-traditional marriage, racism, and how the scriptures talk about women who are divorced. It became a ping pong match between Gwen’s oldest, Evan, who took things seriously and supported the black-and-white policies of the church, and others waving the rainbow flag who made it clear they are loud and proud. “Some of those conversations were very scary. I didn’t want my kids to fight about these issues. I wanted there to be support and love in our home, but through these debates and discussions we made some major breakthroughs in our relationships, learned a lot about the scriptures, tolerance and love, and we are stronger for it.”

In 2021, Gwen, who now works as an author and poet (@leighstatham), married a wonderful man named Blake who had never been married and has no biological children of his own “but took us, and all of this, on without flinching.” Blake became a front-line witness to their very confused, elderly bishop seeing Wren walk into church in a fresh suit for the first time. Gwen says many in their congregation have been very supportive. The temple is the hardest thing for them, because of the gender policies. Wren says, “Basically, because I wear pants to church, I can’t go to the temple.”

When Gwen’s youngest, George, was first able to go to the temple, the whole family—including Blake and Gwen’s ex-husband—decided to go together. Even Wren came and sat in the waiting room. Gwen was touched by the fact that a couple of key people from Wren’s life just happened to be there that day and stopped in to say hi and make them comfortable. Still, this exclusion reminded Gwen of how many of her family members who aren’t in the church couldn’t be in her own temple wedding. “It’s poignant, painful, and makes you stop and wonder why you are doing this when it hurts those you love most. But then you remember, you’re doing it FOR those you love most.”

Wren only comfortably attended combined youth activities and avoided gender divided ones after coming out. One time, they didn’t want to go to an activity and Gwen did something she normally didn’t and nudged Wren out of the car for it. When she returned for pick up, Wren jumped in the car, excited, and told their mom there had been a 12-year-old trans kid present and if Wren hadn’t been there, they would have been all alone. Wren now lives in western North Carolina where they attend college and a family ward. They’re likely the only non-binary LDS member for 150 miles, but Gwen is so proud of how Wren walks a mile in the snow, then carpools with a friend from their university to get to church each week.

Gwen told Wren, “If you’re not there for people to see and meet and get to know, then who will be? It’s hard because everyone usually leaves, but someone has to stay if we want anything to get better.” She continues, “Both of my LGBTQ kids have read the Book of Mormon their whole lives, prayed about it, they love the gospel, they know the scriptures, and they went to seminary. But they rightfully say ‘Where do I fit in?’ I tell them they’re the new generation of pioneers. I say, ‘Think of your ancestors in New England, Britain, Missouri, and Ireland in the 1800’s saying, where does our new faith fit into Christianity? I trust you’re following the path you need to follow. I love you, God loves you, we’ll see what happens. Because we never know.”

Evan’s very strong black and white sense of morality was thrown into an environment at home and at his arts school he couldn't have imagined. But from there, he learned that good friends can grow even if there are major differences of opinion and even within his family. He is currently serving a full-time mission and is applying his experiences to teaching in the field. Evan says, “Loving one another does not mean that you have to agree with every part of life with others. Loving one another means showing respect for others’ decisions or opinions regardless if you agree with them, and voicing concern if necessary.”

Gwen knows and wants her children to know, “Christ is eternal, and he loves us all. In the long run, everything will get worked out–whether you’re active in church or not, living in truth or not, Christ understands us, loves us, and it will be ok, as long as you stay close to Him in the way that is best for you.”

THE SMITHSON FAMILY

Nikki Smithson’s upbringing looked a little different from most of the LDS families who surrounded hers in the pews. In the 1970s, most couples at church were not interracial like her parents, but she has nothing but fond memories of the “great childhood” she experienced and of her “great parents” who are still married (and active in the church today). Nikki was very aware of the controversy mixed-race couples like her parents endured, but she says she has no recollection of learning about the LGBTQ community back then. It was something she was sheltered from, largely because her parents didn’t know too much about it themselves.

Nikki Smithson’s upbringing looked a little different from most of the LDS families who surrounded hers in the pews. In the 1970s, most couples at church were not interracial like her parents, but she has nothing but fond memories of the “great childhood” she experienced and of her “great parents” who are still married (and active in the church today). Nikki was very aware of the controversy mixed-race couples like her parents endured, but she says she has no recollection of learning about the LGBTQ community back then. It was something she was sheltered from, largely because her parents didn’t know too much about it themselves.

Until one day. While at her aunt’s house in her teens, Nikki made a comment about lesbians and watched as her two aunts, Abby and Cindy, gracefully stood up and left the room. Her mom said, “Nikki!” Suddenly 2+2 made sense. Realizing she had lesbian aunts was her only experience with the LGTBQ community until adulthood.

Nikki was sealed in the temple to her high school sweetheart and they had three kids in a row. They bought a house, a Suburban, and as “babies having babies,” almost felt like they were playing house. But quickly, Nikki realized this marriage was one she would need to exit, which proved more difficult than she thought. She was advised by various church leaders that she needed to “stay with her eternal companion.” But Nikki knew she had to make the best decision for herself and her three small children (six years and under); she knew she’d have to navigate this alone.

This experience presented the first cracks in her testimony—not of the Savior, but of church culture. She put her three young boys in Cub Scouts and held callings and “did it all 110% if we couldn’t do it 150%” as a single mom. There were years of inactivity and many Sundays, including every Mother’s Day, where Nikki opted out, unwilling to listen to another lesson about eternal family ideals. Nikki says, “I did what I could to heal and progress forward and not be put in a box where I’d feel fear or judgment. But I always maintained my testimony of Christ.”

Eventually, she married Kurt, who was not a member of the church yet, and “our blended family grew to a total of six boys and one little princess, all under 18 years old at that time.” As her oldest biological child neared puberty, Nikki noticed a constant state of malcontent on their part. There was crying, depression, expressions of wanting to die, and overall, an inability to live an authentic life. Nikki didn’t know what to do, but was willing to explore any measures to help “fix” her child. She says, “Now I know there wasn’t a problem, per se. It was just a matter of discovering the right tools and resources to address their needs.”

The first step for Nikki was to call her ever-so-inclusive aunts, Abby and Cindy, who led her to PFLAG, one of the only LGBTQ support systems at the time near their heavily-LDS Gilbert/Mesa, Arizona hometowns. Nikki went to all the meetings, while Kurt held the fort down with the kids. At PFLAG, the Smithsons were thrilled to find amazing resources and support, though no trans-specific groups. They noticed there were other transgender kids showing up who had no support at all at home. Kurt frequently had to remind Nikki they already had seven kids already, and she couldn’t bring them all home with them.

After finally visiting a pediatric endocrinologist and gender identity counselor (as well as experiencing an affirming Halloween night spent dressed as a female), Nikki’s oldest (AMAB) child understood that their diagnosis of gender dysphoria entailed more–they were trans. Casey was ready to identify as female. The Smithson’s youngest, who was six at the time, was so excited and said, “I have always wanted a sister!!”

Now 15, Casey began her process of transitioning—first working on her pitch through voice lessons, then hormone replacement therapy, and later taking surgical steps to achieve the feminine form that brought her a strong sense of peace with her identity. Almost instantly, while still a teen, her parents noticed an instant sense of confidence and happiness in Casey that had been missing for years. At age 25, @theCaseyblake is now a very vocal leader in the trans community and advocate for other trans youth.

About a year into Casey’s journey, Nikki’s son, Michael, came out to his mom as gay. At 14, he was just starting high school. Nikki replied, “I love you unconditionally, I will support you no matter what. I’m sure I’ll make mistakes, but I’m here for you.” Once again, she turned to PFLAG for support. They advised not to ask too many questions, because sometimes kids don’t know just yet. Nikki says, “I wanted a checklist, wanted to ask, ‘What do you need baby?’ Because his path looked so different from his sister’s. I haven’t been perfect, but we’ve definitely tried to support each other.”

One year later, Nikki’s next biological child, Spencer, came to her and said, “Mom, I need to talk about my sexuality.” Nikki sat down and thought, “Ok. What else do I need to learn? Then, it was the sweetest thing – he was hemming and hawing, and I thought, ‘Baby just tell me, I’m going to love you no matter what.’ And he said, ‘Fine. Mom, I’m straight’.” Nikki laughed and said, “Let me tell you what I told your siblings – I’ve never had a straight son come out to me before, but I am here for you, and support you.’ And I wondered, ‘Where’s the checkboxes to have a straight son? I had no resources for any of these things’.” All this happened in just three short years, when Nikki’s kids were ages 13-15. She says, “I know how to be loud and proud for a trans daughter, a gay son, and now a straight son. We are all happy and living our authentic lives.”

Nikki considers herself a very black and white person. Accepting her kids for who they are came naturally for her, but she was very clear with their friends and family that there would be no level of “grey” tolerance allowed. After Casey first began transitioning, she presented an ultimatum: “You can continue to unconditionally love this child with the Christlike love you’ve always shown, or you can cause problems, stir up hate, and all the kids and I walk together. The choice is yours – run with it or not. It’s ok to have questions and to ask me questions, but don’t address them to my minor child. Come to me. I’ll look up the answers; I’m still learning as well, and I need you to allow that for myself.”

Most of their family chose to show love, and Nikki says that over the years, they have only experienced a few painful hate crime instances in their community. One being when someone drove by Casey at a gas station and yelled a derogatory phrase and threw something at her. The other being when Casey was called out by a security guard after entering the female bathroom at high school with a friend. This was during the height of the transgender bathroom debate, and Casey had been advised to use the gender-neutral nurse’s bathroom in the office. Casey was humiliated by this experience, and never ventured into any bathroom at school again. Nikki became more staunch in her support of Target, one of the first corporations to state that patrons could use whichever bathroom aligns with their gender identity.

Nikki’s family has expanded in love and diversity: Casey’s partner is a trans male, and her gay son, Michael, is polyamorous and has had a partner who continues to perform drag. The Smithsons are outspoken supporters of the drag community in several cities, especially as of late when so much national attention has been thrust toward the St. George, Utah community, in which they now live, due to political debate over HBO’s recent filming of a drag show there. Along with “the most amazing ally couple,” Pam and Gregg, Nikki co-hosts a parent ally group at the St. George Encircle house. Nikki stands united with the LGBTQIA community in their small town and supports several organizations including (but not limited to) Pride of Southern Utah, Mama Dragons, LGBTQ+ Chamber of Commerce, Affirmation, Southern Utah DragStars, Equality Utah, and the family has a side business on Instagram, @OurFamilyDesign, which creates merch for drag performers and other items.

“I have a deep love for the LGBTQ community and I’m passionate about inclusion. We will keep fighting and seeking a fair and just community everywhere, not just St. George. I tell my kids, ‘I want you to be happy, healthy and safe – whatever that looks like for you’,” says Nikki. Her youngest daughter is 16, and “still figuring her authentic self out. I tell her, ‘Whatever it is, just do it and do it well. Be honest, safe, and we’re good.”

Religiously, Nikki has dreaded the question, “Are you LDS?” since she was first a single mom. She recalls, “I knew I’d need to define the religious journey for me and the kiddos. I originally said, ‘Yeah, but don’t judge the church off me or family,’ or, ‘I was raised LDS and kinda’… or ‘I’m kinda inactive’.” But recently, in the last couple years, Nikki has felt more confident saying, “I am unapologetically LDS.” She says this causes people to look at her and think “Ok, do I want to have a meaningful conversation or walk on...”

But Nikki knows, “My Savior’s love has never changed; I’m not worried about my eternal family. Our bishops have been really good to me because I tell them, ‘This is who we are and I choose Christlike love–I don’t have to worry about the whole eternal perspective and who’s sealed to who. I just need to worry about what I’m dealing with now. In my perception, my family is forever because I know we are the same good people. I love our Savior, and I know our God is a just God.”

THE CRONIN FAMILY

Decades ago as Kaci neared high school graduation, her dad would often think back on her childhood and say, “Some people would say Kaci thinks outside the box, but I’m not even sure she knows there is one.” While being raised in an active LDS family with a father who was later called as a patriarch characterized her childhood, Kaci Cronin has always had an adventurous spirit open to new ideas. “The balance of that and being rooted in the gospel can be a great contradiction, but I try to minimize that. Even if you have strong traditions, you can accept the new.”

Decades ago as Kaci neared high school graduation, her dad would often think back on her childhood and say, “Some people would say Kaci thinks outside the box, but I’m not even sure she knows there is one.” While being raised in an active LDS family with a father who was later called as a patriarch characterized her childhood, Kaci Cronin has always had an adventurous spirit open to new ideas. “The balance of that and being rooted in the gospel can be a great contradiction, but I try to minimize that. Even if you have strong traditions, you can accept the new.”

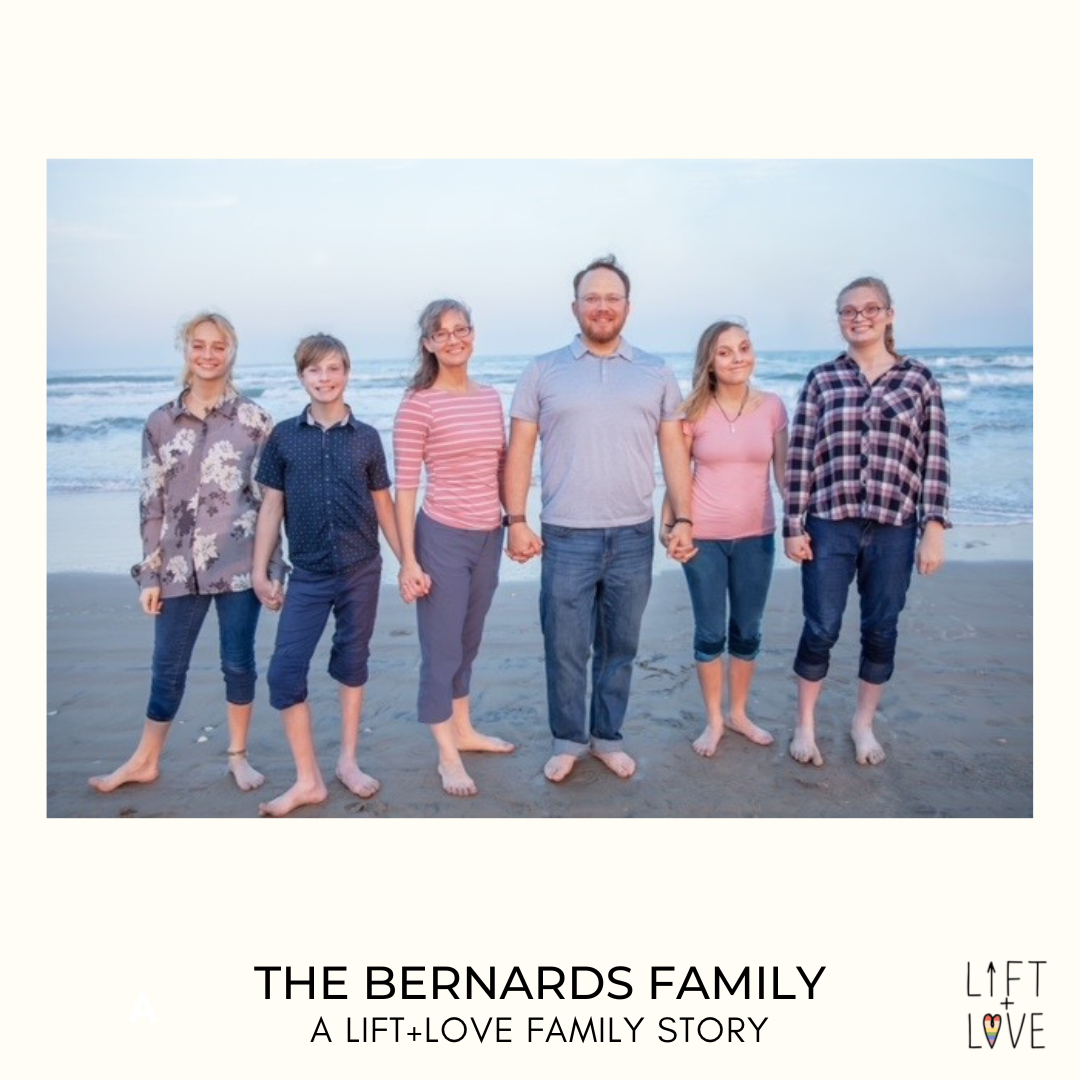

While Kaci was attending a ward for the deaf 25 years ago, learning the ASL she now uses daily as an ASL interpreter at a Mississippi School for the Deaf, she crossed paths with a Deaf ASL missionary. Kevin had also been raised in the church, and the two met, married, and eventually had six kids: Shea-22, Mylee-21, Liam-18, Tierney-16, Maelin-15, and Kennilee-11. The church has continued to be an important part of their family experience in the small town in which they now live, located “just far enough outside Jackson, MS that we don’t lose water all the time” (regarding the recent water crisis affecting the area).

After moving away to Alabama for five years, a couple years ago the Cronins moved back to Mississippi and into a new ward dynamic in which they found they had differing opinions with leadership that were initially hard to navigate. They chose to speak up. For the Cronins, having a Deaf dad means communication has to be deliberate—they don’t holler from the other room and all calls are FaceTime calls. When they feel something, they say something. The Cronins operate off a spirit of the law philosophy and choose to get excited by kids who choose to go to church. During their move, they experienced growing pains with other leaders who prefer more of a letter of the law mentality with strict modesty and morality policing. Rather than step away, Kaci and Kevin leaned in to try to make this environment better, not knowing yet how much their family would soon need it, when one of their own children revealed she, too, didn’t exactly fit in the box.

Back while mothering her first three young kids, Kaci figured she could write a book on expert parenting. All three were soft spoken, clean-faced, shy--the type of kids you could confidently take out of a high chair at a restaurant. She on occasion questioned why other peoples’ kids were bossy terrors. “Then I had my fourth and by necessity had to become an ‘Oh my gosh, I’m sorry, I’m her mom and I’m coming right now’ kind of person.”

Kaci explains, “Tierney was wired differently from the beginning in all facets. As a child, she loved all things scary and intense, including shark attack books and her favorite flip flops with sharks on them.” Kaci says, “She’s still super fun and fills a lot of space wherever she goes.” Tierney loved sports—like, really loved them—and Kaci spent an extreme amount of time bonding with her daughter as she drove her to softball tournaments and basketball and track events.

When Tierney was around 10 or 11, Kevin asked Kaci if she thought their daughter might be gay. Kaci now recognizes Kevin may have been more intuitive in this regard, as Kaci shut down those early thoughts. When Tierney was around 13, she confided in her mom that she was indeed uncertain about her attractions. She thought she’d had crushes on boys, but she wasn’t sure. Kaci observed Tierney didn’t seem to feel or act the same as her older (and later younger) sister did, but Kaci advised they put a pin in it, and just see what happens.

When Tierney was 15, her parents noticed she was spending a lot of time with a particular female friend. She’d come home with a new ring or stuffed animal, and when asked its origin would reply, “My friend gave it to me.” When Tierney wanted to go to dinner with her “friend” and Kaci asked if she needed money, Tierney replied her friend would be picking her up and paying for her. After a few months of this, Tierney said, “Mom, I need to talk to you. I have been dating…” Kaci chuckled and said, “Yeah, I’ve been waiting for you to tell me—it’s kind of obvious.” Later that day, Tierney also opened up to her dad over an ice cream date.

Kaci felt gratitude their daughter felt comfortable with both telling her parents without fearing being looked down upon, and in pursuing a relationship in an authentic way. In a very short time, Kaci and Kevin had many conversations with each other and other supportive family members who all made rapid progress in understanding that they could support Tierney as they believe in a loving Heavenly Father whose gospel promotes hope and happiness. While being the parents of a gay child triggered more concerns related to the church culture and traditions (though not necessarily the gospel itself) for Kevin, Kaci says she came to the realization that, “If the church doesn’t bring us increased hope and peace, then I’m doing it wrong or someone else is.”

Determined to let this mantra both enhance and drive her spirituality, Kaci started to analyze various approaches and opinions to others’ perceptions about raising a gay child. While her family is also supportive of the couple’s dating, Tierney’s girlfriend was initially more hesitant to share her orientation with peers because of her Bible belt surroundings and different Christian faith that delegates some to hell for certain practices. Kaci appreciates that in her religion, at the very worst, anyone considered a dedicated sinner (not that she considers any of her kids as being in this category) would still achieve the lowest degree of celestial glory which, according to LDS doctrine, is “wonderful beyond imagination.”

The Cronins’ oldest son had a brief marriage around the time Tierney came out, which was also instrumental in causing the Cronins to reevaluate religious presuppositions. As the LDS couple was married with a plan to be sealed in the temple asap, from outside appearances, some would say they’d achieved something close to “the ideal.” But as the young couple lived with the Cronins, Kaci was a frontline witness to a toxic, difficult relationship that ended by necessity. In contrast, they simultaneously watched their daughter dating a girl, an LDS cultural taboo, but saw the sweet happiness in that relationship. Through this, Kaci has surmised, “You can find happiness, health and beauty in places you never thought to look. I’ve realized some of my goals are now much more primal for my children, in considering what is necessary on a human level to be able to function well. In the end, I want them to be happy, cared for, and to feel supported.”

During the pandemic lockdown, Tierney further surprised her parents by requesting a school and extracurricular change. Rather than continuing with her intense athletic commitments and the small, rural Christian school she’d attended thus far, Tierney wanted to shift to singing and playing the guitar and other instruments and to transfer to a nearby large public school where she’d audition for theatre. Kaci says, “Is there a box? No. When I posted about her not playing her lifelong sports the next year, it was kind of funny because that got more of a surprised response than her coming out. I’m proud that she’s grown and matured enough in her life already to make decisions for her own path, even beyond her sexuality. She’s realizing, ‘What do I want to invest my energy into to become what I want to become?’ I love her example that we have these things inside of us that we might not tap into if we’re not willing to try something new and go to new places to discover who we are. Because of this part of her personality, we all get to have these adventures with her.”

Tierney ended up landing the lead in the school play and when her school’s production advanced to state, she was personally named as part of the regional All-Star cast. She is still dating her girlfriend 16 months later.

When Tierney came out, Kaci was her ward’s Relief Society President. Since, their son Liam has gone on a mission where in the MTC, he was one of the trainees in his class who was unphased and supportive when their Spanish instructor opened up to the class about being gay. Kevin has since taken a job in Boston where he has surprised his progressively minded colleagues as “the guy from Mississippi who shows up wearing a rainbow bracelet.” The Cronin family are still part of the same ward, and they appreciate that their bishop has reached out to ask how they can make Tierney feel welcome, and no one has been confrontational or contentious about Tierney’s orientation or attendance at events (FSY, girls camp, etc.) that require bunkmates.

Tierney recently did attend FSY and had an intense spiritual experience she was eager to share at the first opportunity she had to bear her testimony. Over the pulpit, she told her ward she went into FSY wanting to know if she was really loved by her Heavenly Father, as is. Tierney reported that she received a testimony that, “He loves me, He still communicates with me, he hears my prayers. I’m not cut off at all.”

The entire Cronin family has shifted their beliefs to center on the personal relationship they each can receive with divinity and the foundation that comes with that. Kaci says, “FSY was a turning point for my daughter as she received a personal testament that she has a place and is valued. My prayer as her mother is she’ll always carry that with her regardless of her standing and involvement with the church.”

When it comes to parenting, the Cronins acknowledge that some out-of-the-box adventures their children have brought to their world are as unpredictable as the state of the Jackson, MS water supply. Some adventures are hard, and some are great. But Kaci says, “At the end of the day, that’s where the joy and connection come in our family–through continuing to show up for one another.”

KEN TAYLOR & LISA ASHTON

When she was four years old, Lisa Ashton and her older brother Joe took a walk around the block with their father. A walk Lisa would never forget. As they circled their Rancho Cucamonga, CA neighborhood, Ken Taylor assured his kids it was in no way their fault, but he would soon be moving out of their home. He and their mother were getting a divorce…

When she was four years old, Lisa Ashton and her older brother Joe took a walk around the block with their father. A walk Lisa would never forget. As they circled their Rancho Cucamonga, CA neighborhood, Ken Taylor assured his kids it was in no way their fault, but he would soon be moving out of their home. He and their mother were getting a divorce. After Ken moved out, Lisa took many walks around the same neighborhood over the years, but often by herself. Her brother was four years older and didn’t want to hang out all the time with his younger sister, and their single mother was often gone at work.

Lisa spent years processing that her life just looked different from that of many of her friends.

When she and Joe spent every other weekend as well as vacations with their father, they observed Ken had a roommate they called “Uncle Ed” who lived with him for many years. Lisa remembers it being a little confusing. Ken and Ed had lots of other male friends they hung out with (some with kids of their own), and she remembers them giving disapproving looks when her brother once said “That’s so gay” in a derogatory manner. When Lisa was 11, Ken finally felt it was time. He told Lisa, “I have a lot of male friends who are attracted to men.” Lisa asked, “Would you be gay?” With a deeply pained sigh of relief, Ken said yes.

When Lisa turned 14, her brother had moved off to college and she was living alone in a big house with her mother, Teresa (who Lisa and Ken agree earned her nickname “Mother Teresa.”) By this time, Ken felt it was his turn to be the full-time parent and all agreed to the arrangement. Ed and Ken broke up shortly after, and Lisa and Ken moved into an apartment in Dana Point, CA. When Joe returned from his LDS mission, both kids lived with Ken for a short time before Lisa went to BYU and her brother returned to college. Of having a gay father, Lisa says, “It was the 90s; things were so different back then.” She knew her childhood was atypical. She wasn’t sure who she could trust with this information. As an adult, she now freely talks about her story and lessons learned along the way about unconditional love and acceptance learned from both of her parents.

Ken’s upbringing was also atypical. He was born in 1950 in Washington D.C., the seventh of eight kids of parents who were married in the temple. Due to his father’s job as a foreign service officer for the state department, they moved around internationally, spending time in Mexico, Austria, and Canada in between stints in the states. Ken said he was always active in the church, but he recognized that something about himself was different. While living in Vienna between the ages of 11-15, Ken was involved in an American scouting program there and dated girls like all the other guys did, but he found it interesting that the most popular boy in school came on to him. Ken did not want to resist and thought, “If he can do that, why can’t I?”

Ken spent ages 15-18 in Montreal, where as a high school student he met a fellow gay peer named Eric from Holland who was active in the LDS church and engaged to marry a girl. They eventually had six kids and later got divorced, then remarried, then divorced again. Eric now lives in Holland with his boyfriend. But back when they were young, Eric had asked Ken to run away with him and forget about everything. At the time (1968), Ken couldn’t fathom doing something like that due to the church culture in which he’d been raised and was trying to make work.

Instead, Ken went to BYU after graduation. His father had just retired and his whole family moved to Salt Lake City. It was 1968, and Ernest Wilkinson was president of BYU. In his “welcome speech” to the university, President Wilkinson uttered those now infamous words:

“We [do not] intend to admit to our campus any homosexuals. We do not want others on this campus to be contaminated by your presence,” and invited them to leave immediately. At the time, Ken felt so deep in the closet, he didn’t admit he fit into that category; rather he was convinced the church would help him “get out of that.” He was surrounded by returned and preparing missionaries and decided he should take the same course. At 19, Ken was called to serve in eastern France and was excited he’d be able to put his Montreal-acquired French and German to good use.

Before his mission, his stake president asked if he was worthy to serve, and Ken said, “I wouldn’t be here if I wasn’t.” But the pressures of the MTC got to him, and feeling guilty, he went to an authority there to confess his history. The man said, “I don’t know much about this but you need to drive up to Salt Lake and see (Elder) Spencer W. Kimball,” who was an apostle at the time. Elder Kimball interviewed Ken in detail about everything he’d been involved with and said he’d still let him serve his mission as long as he promised to write him once a month, and warned that if he ever got involved in anything, he’d be sent home immediately. He also told Ken never to talk about this part of him again with anyone. Ken was petrified, and says he never did anything immoral by the church’s standards on his mission.

On his mission, Ken told just one companion about his attractions, and the companion told Ken that his father was also gay. This young man had gone on a mission hoping his parents would get back together, but his dad didn’t want to because he had a gay partner. He wanted to keep that relationship while still being a father. Subconsciously, Ken recognizes this became the first model for how he would later choose to live his life.