lift+love family stories by autumn mcalpin

Since 2021, Lift+Love has shared hundreds of real stories from Latter-day Saint LGBTQ individuals, their families, and allies. These stories—written by Autumn McAlpin—emerged from personal interviews with each participant and were published with their express permission.

THE HONG FAMILY

We reached out to the Hong family after their father posted a talk he gave in their ward on how doubt and having a gay son helped him become closer to God. Here is their story…

We reached out to the Hong family after their father posted a talk he gave in their ward on how doubt and having a gay son helped him become closer to God. Here is their story.

There are some perks to being a rule follower. People generally heap praises and smiles upon you as you check the boxes: seminary graduation, leadership callings, BYU, institute, mission, scripture reading 30 minutes a day, all while praying morning and night you’ll find a woman to marry and promising God you won’t do anything wrong IF… because you know the levity of that ask. Isaac Hong (now 30) did it all well in his southeastern Idaho, predominately LDS hometown, and later in Provo, because as he says, “I’m a really good rule follower.” He came home from that mission ready to obey his next task: to find a woman and marry her within a year of his homecoming. And then… reality hit.

Isaac remembers the moment he realized, “Oh shoot; this is not working. I cannot get myself to do it.” Several difficult conversations he had with himself resulted in a journal entry in which for the first time he acknowledged, “I think I’m gay.” As time passed, Isaac spiraled and knew he needed to talk to someone. As he tried to lose himself in service and distraction, he realized he was at risk of actually losing himself. “I was exhausted, trying so hard to do good. It got to a point I was breaking. I would drive to work and hope something might happen to me along the way, because no matter how hard I tried, I couldn’t change this thing about me.”

Wanting to engage with his parents while home visiting, late one night, Isaac went into their room and asked if they could talk. And they did. He recalls there was a lot of listening and a lot of asking what things meant, and for him, a huge sense of feeling overwhelmed and relieved at putting it out there, but also actualizing that he didn’t know exactly what this would look like—especially if he left the church. At the time he thought he’d stay highly active. His dad, Don, serving as bishop then, also envisioned that possibility, and even imagined his son gracing one of the Mormonads circulating at the time. Don could see his son in the interview chair, saying, “I’m gay and I’m a Mormon.” Don’s wife, Jenny, didn’t see Isaac’s future quite the same.

As the mom of four kids she calls “amazing,” Jenny was just coming off a parenting payday. Isaac had come home to join family in supporting his sister as she received her endowments. “It’s amazing how prideful we can be,” Jenny laughs. “I went to bed thinking three down, one to go. Wow, what a day…” But there had been many days—or years—since Jenny had first sensed her second oldest child might be gay. She remembers observing special qualities back in kindergarten as Isaac would reach out and befriend those who needed it. She continued to watch through high school, wondering when he’d say something. After his mission, she wondered if she might have been wrong; but she always sensed that behind his bright, overachieving smile there was a sense of loneliness and misery. She says, “I’d pray—whatever this is, please let him be able to be open about this.” The night he finally opened up, Jenny remembers telling him, “I love you, I’ll support you, whatever your journey looks like.” Her memory of that night also included Isaac sitting on the foot of the bed, with a giant canvas of a bedspread between them. She says she wishes she’d done more--invited him to sit next to them, maybe said, “give me just two minutes to put sweats on so I can give you a hug.”

Jenny assures they weren’t the picture-perfect family, but says, “We were guilty of trying to check the boxes. We tried to do daily scriptures, evening prayer, and family home evening—even taking a stand that Monday night basketball practices had to end by 7pm so we could have FHE. But maybe we should have focused more on making sure our kids simply knew we loved them no matter what. Focusing on checking the boxes probably sent the wrong message.”

The Hongs acknowledge they endured some ungraceful moments. When Isaac told his dad he was going to start dating men, Don remembers saying, “Well, if I’m being honest, I’m not as excited for this as I would be about your sister seriously dating someone.” That comment hurt Isaac and he said, “Why wouldn’t you want me to find someone to share my life with and be happy?” Don looks back now with regret, and reflects he was just trying to process everything. “I was probably 50 steps behind Isaac and spent a lot of those early days trying to catch up.” But as time passed, Isaac credits his dad for being a genuine, curious person. When Isaac would say, “Hey Dad, you hurt me; this hurts,” Don wouldn’t take it personally, but instead would say, “Help me to understand why.” That approach allowed the two to develop an open and honest relationship in which Isaac offered his dad a lot of patience as they tried to come to a place of understanding. Referencing BYU professor and author Jared Halverson’s first stage of faith in Don’s talk, he says, “I was stuck in the creation stage.”

Don says Jenny, who had grown up with a more open mindset, was way ahead of the curve in understanding and supporting their son. So it was a punch to the gut when Isaac called her one day, sounding happier than he had in a long time. He said he had the perfect solution to the current family crisis. A close family member had recently received a severe liver disease diagnosis and would need a transplant within the next five years. Isaac volunteered, “When that day comes, I’ll just figure out a way to give him mine.” That result would be fatal; Jenny fell apart. She says, “Obviously, that’s not an option—we wanted them both to live the healthiest, happiest lives possible; they deserved that. That day, I knew we had to find a way for Isaac to know he deserved to experience joy and happiness. Whatever road that was, we’d go down together.”

She and Isaac would call each other every day. On one of those calls, she could tell he was having an especially hard day. Jenny remembers starting to cry and telling him her heart was breaking. She remembers it made him feel bad he had upset her, but at the same time, it healed him to know she was mourning with him. It was easy for Jenny to cheer him on. When Isaac called her to say he was going to start dating, Jenny was elated. She loved hearing the refreshing excitement in his voice as he’d talk about a guy he found to be “super good looking.” She says, “I’d been waiting so many years to hear giddiness in his voice; I loved it.”

When he first started dating, Isaac was still attending church. After a couple of years, Isaac met his now partner of three and a half years, Brock. A Utah native, Brock had also grown up in the LDS faith, and in his coming out journey, had been negatively impacted by religion. Isaac says, “Brock was able to clearly express it in ways I hadn’t heard it articulated before. So much resonated, and my heart hurt for him... I was upset how the church had hurt him and no longer wanted to be active.” Isaac says that disaffiliation almost felt like another coming out, which was another gradual process for his family. But as they had worked to develop a relationship of being honest, curious, and compassionate, Isaac would vocalize a heads up to his parents–whether it was that he wouldn’t be wearing his garments on the next family vacation, or that he and Brock would prefer to share a room.

Don says, “I love Brock! Both he and Isaac are some of the most thoughtful people you will meet. Brock’s very good at sharing a fair perspective on many topics, whereas I often come at them with my biases. He has helped me see things in an atonement stage way. It’s very humbling.” After graduating from BYU, Isaac got an MBA at the University of Utah and now works as a product manager for Mastercard. He and Brock met at a Utah gathering of like-minded friends. Together they love getting out and exploring Utah via paddleboards, lakes, reservoirs, the mountains, their swim team, and they also enjoy playing pickleball, and “chilling and watching TV.”

Isaac says he is the extrovert of his siblings, but his siblings are all “loud supporters” who have also wholeheartedly welcomed Brock into their family. Older brother Jacob (who’s married to Stephanie, and father to their kids Ella, Gracie, and Simon) is likely the most reserved sibling, but made it loud and clear that Isaac and his partner are always welcome into their family’s Minnesota home. Isaac’s sister Calie, 27, lives in the lower portion of Isaac and Brock’s townhome in American Fork, and the Hong’s youngest, Lacy—19, is going to UVU and getting married this summer.

“Having a gay son has been a gift,” says Don. “It has opened my eyes to just how many people don’t feel like they have a place at the table, and I want to do my part in making that table full.” Don recently gave a talk in his ward’s sacrament meeting that’s been widely shared online about ways people can do better to honor those on their faith expansion journeys. They’ve been warmed by the response in their town as many who had been silent from the margins have connected with the message and shared their stories with them. Jenny hopes people realize the church does not take the place of your family and “we should never feel it’s one or the other. There is infinite grace, and I look to a day when everyone can simply love. Love people exactly where they are and without judgement.” Isaac says he and Brock no longer attend church, and doubts it could ever become a place where he would feel safe or want to return.

While sitting beside his parents, it’s clear the three have worked hard to come to a place of understanding and unconditional love. Of the journey he’s taken alongside his parents, Isaac says, “We may have different perspectives, but at the end of the day, there’s grace and beauty in what each is trying to do. It’s an ongoing dialogue.”

Don’s talk can be found here: https://www.facebook.com/don.hong.56/posts/pfbid02TEg3BLtu9Ec7WTYZpPu4YEza6oAcNG7V44T2CzYEy2ebFTZABaa5DgPM8ZicGnjsl

BLAIRE OSTLER

As a ninth-generation descendant of Mormon pioneer stock, notable author and philosopher Blaire Ostler says, “For me, Mormonism is not just a religion, but part of my culture and identity--it’s almost an ethnicity. It’s how I think and see the world. I joke I couldn’t not be Mormon, even if I didn’t want to be—even my rejection of some parts of it is so Mormon.” Equally, Blaire is bisexual and intersex and identifies as queer, saying, “That’s also always been a part of me; it’s how I see the world and navigate life.” Her landmark book, Queer Mormon Theology (published in ’21 by By Common Consent Press), chronicles the juxtaposition of these unique traits that cast people like her in the margins of most circles. But while Blaire was told these two identities couldn’t coexist together, she absolutely knew both existed inside of her. “As one can imagine, having a conflicting view of self can tear at you.”

As a ninth-generation descendant of Mormon pioneer stock, notable author and philosopher Blaire Ostler says, “For me, Mormonism is not just a religion, but part of my culture and identity--it’s almost an ethnicity. It’s how I think and see the world. I joke I couldn’t not be Mormon, even if I didn’t want to be—even my rejection of some parts of it is so Mormon.” Equally, Blaire is bisexual and intersex and identifies as queer, saying, “That’s also always been a part of me; it’s how I see the world and navigate life.” Her landmark book, Queer Mormon Theology (published in ’21 by By Common Consent Press), chronicles the juxtaposition of these unique traits that cast people like her in the margins of most circles. But while Blaire was told these two identities couldn’t coexist together, she absolutely knew both existed inside of her. “As one can imagine, having a conflicting view of self can tear at you.”

A self-described “military brat,” Blaire grew up attending LDS wards with anywhere from 15-600 congregants, in meetinghouses from Korea to California. Having this wide exposure to “church,” she saw how it means different things to different people. Outside of Utah, she saw the church as the built-in community you find wherever you go. It was about ensuring everyone has access to food, healthcare, language—basic needs. “That was more important than some of the cultural debris that gets mingled with the gospel. For us, the gospel was ‘Love your neighbor; take care of each other’.” She was also raised by a Catholic mother who converted to the LDS faith—somewhat of a universalist who held there is more than one way to find God. Blaire was given tools to deconstruct—a process that for her began around 14.

At this time, she was coming to grips with the fact that she was biologically queer with intersex characteristics, and also bisexual, experiencing sexual attraction and desire towards a diversity of genders. “It’s difficult to overstate how much it messes with your brain to be taught two conflicting messages about yourself as a Mormon woman, that: 1) your most important goal is to have a temple marriage and raise babies to go with you to the celestial kingdom, and 2) queer people destroy families, are promiscuous, die of AIDS, and corrupt society.” Blaire’s most difficult struggle was to get past this engrained dichotomy of being told “You’re supposed to do this,” but “As a queer person, you will fail at it.”

Blaire, who is now on the editorial board at Dialogue, wound up at BYU Provo where she met her husband of 20 years, Drew. After many moves and jobs, they now again call Provo, Utah home--the Y mountain just outside their doorstep. Blaire jokes her 20s were spent either pregnant, in an operating room, or a hospital–having and nursing babies, and having surgeries that would allow her to do so as an intersex person. “It was a decade of trying to be the ideal version of a Mormon woman in every imaginable capacity—from the way I looked, sounded, functioned, existed. It will burn you out—you can only do it for so long.” Blaire and Drew ultimately had three children, now ages 15, 13, and 10.

In her words, she spent her 30s in a therapist’s office, trying to heal “from all the chaos of trying to fit a narrative that my body—my biology—was not made to create babies. It was a dangerous activity.” She says, “I was convinced I had to prove myself by doing these things, not even caring if I lived or died. That was obviously a low point.” After passing out on the operating room table after having her third child, Blaire chose to get sterilized for her own safety. Her 30s afforded her time to heal her body from the surgeries, her heart from the spiritual trauma, and her mind from the things she’d been told about her purpose. It was during that process that she decided to write her book.

Per Blaire’s educational background, philosophy plus religion equals theology. Via this contextual podium, Blaire ventured into a possibility space where she could be both queer and Mormon? “Queer” is an intentional word for Blaire, who both supports the reclaiming of the word as one with positive connotation (as demonstrated by Queer Nation since 1990), and recognizes how, in its blanket simplicity, it affords many the privacy and legitimacy they seek in a world that sometimes requires labels to consider and afford equitable rights. She also recognizes it as a word similar to “peculiar,” which has likewise been lauded in Mormon philosophy to be a good thing. Further, Blaire reclaims and esteems “Mormon” as a positive term, citing its inclusion in scripture. Her book provocatively explores the inherent coexistence of what it means to be queer, peculiar, and Mormon, and invites the reader to see things that are hidden in plain sight.

Further propelling her quest to upend presuppositions is her role as a mother of three, with Blaire youngest also identifying as queer. “It’s interesting because as a queer parent, my daughter was essentially raised at a Pride parade. We assumed she was simply reflecting what she saw. But over time, it became apparent that this was her. I have a beautiful, queer, 10-year-old child.” But this made things different, regarding church. Blaire found herself becoming protective and concerned with what her Primary-aged daughter might be exposed to. “It’s one thing to roll the dice with yourself; it’s another to do it with your child.” Blaire’s family has taken a calculated approach to their church activity, choosing to support this activity or class or speaker, but perhaps not show up for those deemed riskier. “I didn’t want her to grow up being taught that she was anything other than a beautiful child of God—and strangely enough, she might be taught otherwise at church.” In this Ostler household (no close relation to Richard Ostler’s), there are a variety of faith transitions going on, and Blaire presumes each may land at different spots as they have varied perspectives on Mormonism, church, and God. But “at the end of the day, Mormonism means family. We all agree to take care of each other, and if we do that, then we did our job… This isn’t necessarily a rejection of the church, but a manifestation of our most sincerely held beliefs.” She explains it as the orthopraxy of her orthodoxy and acknowledges that while some may not understand, Blaire views her best perch as one that respects people where they are.

“The thing I learned from Mormonism and how I was raised is that life was about creating eternal families. At the end of the day, when the church is in conflict with my eternal family, I err on the side of family.” She continues, “The church was started by a man desperately trying to connect families and relationships through sealings. When I pick my family, I’m picking Mormonism, by not letting an institution come before my family. Strangely, some conflate the institution with their beliefs. I see the Church more as like a ship, and Mormonism is the people on the ship working together. But some on that ship (the institution) want to throw the queer people overboard, and if people are getting thrown off the boat, I’m going with them--the least of them. Guess who else did that? Jesus. He went with those who were cast out and left behind. The gospel is so much more than just a ship, even though a ship is useful.”

Blaire feels that even her presence causes some cognitive dissonance for others. “Because what I say is steeped in gospel and scriptures, sometimes people have a hard time coming to grips with it. It’s a view of the scriptures that most aren’t accustomed to.” But she honors religious plurality as found in universal concepts like the Golden Rule. “I feel like we need to take it to the next level in Mormonism and recognize when something on the ship isn’t working. We’re a religion of ‘Is this working?’ And if not, we honor change through ongoing revelation. The monolithic narrative of hetero supremacy isn’t working as so many family structures look different,” she says, addressing the single parent, divorced, widowed, polygamous, adoptive, and never married members now casting the nuclear or “traditional” family as a new minority. “We need to recognize our faith community as much bigger than we thought. We’ll be stronger for our diversity and inclusion. Imagine all the beautiful queer youth, queer missionaries, and rising young adults we’re losing because we looked at their queer gifts and said, ‘No, we don’t want your unique contributions.’ We are missing out.”

Referencing the body of Christ as found in Corinthians, Blaire explains, “We were never meant to be the same. Sometimes we look at our differences as a place of conflict rather than beauty and opportunity. If one’s good at writing and one good at building, wow, what a great opportunity that is to help each other! Is the body of Christ all hands or feet? No, we have different parts that work together cohesively. But we’re afraid, and sometimes we look the other way because we don’t want to see the parts of the body of Christ that are suffering. However, by recognizing suffering and mourning with those that mourn, we take the first step to making things better.” Acknowledging those deficiencies, like when the church changed its priesthood and temple exclusion policies and started the perpetual education fund to further restore equity, brings Blaire hope for further change. “Imagine the powerhouse the church could be if all members were ordained to the priesthood instead of half. Or if we didn’t push out 5%+ for being queer; imagine how much stronger we’d be. When we cut people off for insignificant differences like race, gender, or orientation, we’re undermining ourselves.” She recognizes this awareness is needed outside of the church, as well, especially now as people along the LGBTQIA+ spectrum face a litany of hostile legislation and infighting even in the secular community.

While she considers the gospel of Jesus Christ as her personal guiding faith practice, Blaire says she honors each individual’s ability to choose their own healthy path. “If a queer person is happier in a hetero marriage sealed in temple, or if another no longer affiliates with the church because it’s psychologically traumatizing, I support both. You have to go where your basic needs are being met, and you get to decide what that looks like—especially queer people. I have a hard time believing our Heavenly Parents don’t want our queer kids safe more than anything – I can’t imagine any loving parent thinking that, let alone a godly parent. We need to support each queer person wherever they land.” She has reframed her paradigm of God and now considers the concept of God to be a big heavenly family where all are connected. “God isn’t he, or she, God is they—God is all of us in one big eternal family… When we honor our families, we’re honoring God and the greater heavenly family we’re all a part of. Sometimes we think of God as a monster who wants to punish and harm us…I think we limit God’s compassion through our own imagination. I believe in a God that is more compassionate, loving, and benevolent than we could possibly imagine.” Blaire says as a parent herself, she views her role as “a heavenly parent in-training, trying my best to care for my children. Will I send them to a room, activity, or meeting that’s harming them and causing panic attacks? No, I’d rather say, ‘You are that you might have joy.’ This is what we’re doing as a family—prototyping a heavenly family. We stick together; we don’t kick people out on account of our differences.”

Of her faith practice, Blaire especially loves taking the sacrament as it symbolizes the “breaking of bread with my people, especially when we disagree. That’s when we need it the most.” She continues, “We’re all members of the body of Christ and this equates our commitment to each other and to adhering to His gospel.” Again, she is taken back to meeting the primal needs she identified in childhood: does everyone have food? Housing? Care? Health? “That is what Jesus did. Here, our basic needs are met.”

“In Primary, we are taught to love one another. Loving one another is how we find our way home,” says Blaire. “Our queer mantra is ‘Love wins.’ And I truly believe that. Love wins. Or in other words, charity never faileth.”

**If you would like to learn more about the intersex population and what it means to identify as genderqueer, Blaire recommends the books Sex and Gender: Biology in a Social World by Anne Fausto-Sterling and Evolution’s Rainbow: Diversity, Gender and Sexuality in Nature and People by Joan Roughgarden. Blaire’s book, Queer Mormon Theology, is available on Amazon and Audible.

THE ERVIN FAMILY

Every month, parents of transgender and nonbinary kids can join a Lift and Love online support circle facilitated by Anita Ervin of Canal Winchester, Ohio. It’s a topic with which she is very familiar. When Oliver—22, and Rome—19, the oldest of her four children, are both home together, the Ervin house is noticeably louder and filled with laughter. While the two say they fought sharing a room as children, they now share an inextricable bond. Rome credits Oliver for making their coming out journey much easier at age 16. Anita admits Oliver put them all through a learning curve when he first identified as queer in 2018. Rome says, “Oliver got the messy; I got the ‘all good’.”

Every month, parents of transgender and nonbinary kids can join a Lift and Love online support circle facilitated by Anita Ervin of Canal Winchester, Ohio. It’s a topic with which she is very familiar. When Oliver—22, and Rome—19, the oldest of her four children, are both home together, the Ervin house is noticeably louder and filled with laughter. While the two say they fought sharing a room as children, they now share an inextricable bond. Rome credits Oliver for making their coming out journey much easier at age 16. Anita admits Oliver put them all through a learning curve when he first identified as queer in 2018. Rome says, “Oliver got the messy; I got the ‘all good’.”

In summer 2018 at age 18, Oliver came home from BYU-Idaho and told their parents he identified as pansexual. This first happened in a car conversation with his mom in which Oliver asked if he would ever be kicked out of the house. When Anita passed the turnoff to their neighborhood and kept driving, Oliver was startled and feared he was about to be dropped off for good anywhere but home. But instead, Anita drove to a nearby park where they could have what turned out to be a complex conversation in peace. Anita assured Oliver that she would never kick him out unless it was something for his own good, not for his orientation. Almost 18 months later in December of 2020, Oliver (who was AFAB) came out as trans-masculine to Anita by sharing a handwritten letter he was going to send to his grandmother for whom he was originally named. Oliver’s coming out process has continued in a manner in which Oliver typically explains things to his mom, who then shares them with his dad, Ben. A couple months later, during a dinner conversation, Oliver explained to his siblings that there is a spectrum of gender identity with males on one side and the females on the other. Oliver shared he falls just left of center, on the male side, and would prefer to use the pronouns he/they and change their name.

“Growing up in a heavily Mormon family, I didn’t have the words for gender or sexuality and didn’t know what gay people were or gay marriage was until I was 12, and they read that letter in church about gay marriage. It just wasn’t discussed. I didn’t know trans people existed until well into high school. So I didn’t have words for it, but I knew I wasn’t the same as everyone else. I felt like an alien, trying to pretend, because I didn’t have the same guide book,” says Oliver. In college, they met their first queer person inside the church. In their time away from home while at school, Oliver explored how he best identified until he settled on what felt authentic. Oliver, who says he didn’t “get the hype” and hasn’t felt a connection to God since the age of eight, has removed his name from church records. He spent most of his adolescence with his family in a conservative ward in Oklahoma, where the Bible Belt climate often compared people like him as akin to murderers. Oliver is now more open in his spiritual practice, believing that actions beget consequences but does not adhere to a specific organized religion.

After spending many years babysitting and later working at a day care center, Oliver is now comfortable being out at their current workplace. He loves movies and TV, reading, painting and customizing black Vans shoes, and does a lot of art. Oliver has been dating Mya (AFAB) for almost three years, and also identifies as unlabeled orientation-wise. Oliver explains that often, LGBTQ humans first have a sexuality crisis, then a gender crisis, then another sexuality re-examination. Of he and Mya (who uses they/she pronouns and is bisexual), who has been with Oliver through his transition, Oliver says, “We’re not pressed on labels; it just is what it is. We both feel a little too old to lie awake at night trying to find a label or a box to put ourselves in. Sleep is already difficult; I’m not losing more over this.” Oliver and Mya also identify as “kitchen table” polyamorous, which they explain as not really a sexual thing, but more like being open to consensual emotional connections with others. The Ervins really like Mya, and Rome has told Oliver more than once they can’t break up because Rome and Mya are “besties.”

Rome, who was also AFAB, identifies as gender queer and bi-curious. (They have no preferred pronouns.) They selected the name Rome awhile ago, and Anita laughs she still hears the B52’s lyric “Roam if you want to” every time she calls her child’s new name. Growing up, Anita says she and her husband Ben were used to pairing off their kids, having two of each, and referred to their brood as “the girls and the boys” (younger siblings include Connor – 14 and Maddox – 12). But now, it’s the “gremlins and the boys.” Oliver laughs that he and Rome “are a little freakish” and so the name suits them well. Anita is very grateful that both of her oldest kids’ anxiety has improved since coming out.

Rome enjoys making jewelry, specifically earrings, out of miniature things, and loves the aesthetic (not the drug) of the mushroom. They also enjoy true crime, creating art, watching Criminal Minds, Minecraft, and claim they have an “unhealthy love of Mexican food.” Rome has done a year of college and is working at a BBQ joint for the summer.

In 2020, after listening in on a conversation Anita had with the Emmaus (LGBTQ and faith-affirming) group, Rome confided in her mom: “Mom, I think I might like girls.” This time, Anita responded more along the lines of, “I’ll love you forever and ever and ever,” laughs Rome. Anita recalls counseling Rome to not rush to label themselves, that they’d figure it out. Rome is grateful Oliver “paved the way for my ability to come out comfortably because he instigated the learning process for our friends and family,” and that they’ve had a family willing to accept them, no matter what. Rome also has benefitted from a more accepting ward in Ohio where several women wear pants to church and it’s easier to blend in. Anita encourages this, after observing Rome’s choice to wear slacks and a vest to prom. She believes Sunday dress is about “dressing your best” as your full self for the Lord, not adhering to some cultural norm.

Before Oliver came out, Anita says she always considered herself a “middle of the road, cliché Mormon.” She went on a mission, married in the temple, never turned down a calling. When Oliver first approached the LGBTQ subject with her, she didn’t know what to do – should she steer him toward the bishop? She didn’t want him living the life of shame she’d seen another close family member endure. Anita says, “As I prayed about what to do the only answer I got was to love him the way God loved him—fully. It was not my job to ‘teach more truth’ in an attempt to ‘fix’ him.” In the beginning, she and Oliver concur things were rocky; there were lots of tears. But Anita emphasized maintaining a strong connection with her child. She has close ally friends in her ward who she says got her on the right supportive path and to a place where she realized she could be all in with her family and all in with the church. “I loved realizing I didn’t have to choose between fully supporting them and being present in their lives, and being committed to my faith as well. I could do both.”

The Ervins have also reassessed how they teach faith at home, focusing more on how to develop a connection with Christ than follow a pamphlet of do’s and don’ts. “If you strip away everything else, at the core, it’s Jesus Christ and His grace that saves us, not going through the motions of church activity. I can’t limit Christ. I can’t say I have to expect my kids to live a certain way to be saved by Christ. I think He’s big enough to handle the complexity of their lives.” Anita says they have definitely moved on from a place of grieving over lost expectations, and now are able to see the humor in things. Their driveway is witness to the frequent “Can you make that straight?” joke, referring to a crooked parking job with a well-received double entendre.

A significant realization that’s helped Anita came from Richard Ostler’s second Listen, Learn, and Love podcast episode in which he deconstructed three partitions of church: the Church of Jesus Christ. The restored gospel. And the organization of the church. Anita likewise deconstructed her testimony and is able to safely linger in the first when things get hard. She can just focus on maintaining a pure connection to Christ. As looming fears of policy changes regarding trans individuals both in the national landscape and at church brew, Anita is choosing to focus on the one thing that won’t change: her faith in Christ.

Anita says, “I have faith and beliefs which haven’t changed, but I can respect where my kids are coming from. If they don’t go down the path I’d hoped, it doesn’t destroy my perspective. It’s okay for them to choose their paths; it’s only complicated because I don’t know the answers yet. But a pain point for me is that I see my kids in their gender journeys and some of the policies towards trans individuals, and I feel like they’re being treated like wolves instead of sheep. I want some recognition that they’re sheep.”

Oliver concurs there’s an untold level of pain kids like him experience. “The first time I thought about ending myself, I was eight years old… If people truly knew the level of discomfort, they would choose to learn. If people knew they could literally save a child’s life by listening and trying, they would.” He says Wrabel’s song “The Village” (lyrics below) perfectly sums up how important it is to listen to the trans experience in religious environments. Anita also laments the suicidality rates of trans individuals, as found at the Trevor Project. She’s had flashes of “What if? What if I had been the parent who’d said, ‘Not in my house’. I probably would not have all of my kids with me today. This isn’t just about us. We all change in our lifetimes; we all grow. People say, ‘What if it’s a phase?’ I respond, ‘So what if it is—this is real to them right now, and so right now I’m showing up 100% on their team. As their mom, I’ll do what I need to do to get them through the next five, ten years.”

What pains Anita most when she leads the parent support group is witnessing the sadness of families whose kids are being othered and excluded. “Too often when the kids don’t stay, the whole family goes. I feel that loss keenly. I understand when families step away. People need to realize that when they have those casual conversations against our kids, they are often sitting next to a parent of a nonbinary or trans child…” She fears the exponential hurt that may come in the near future for many. “Of all the places on earth where people should feel love and acceptance it should be among the followers of Christ and in His church. Unfortunately, that’s not always the case.”

Lyrics

No, your mom don't get it

And your dad don't get it

Uncle John don't get it

And you can't tell grandma

'Cause her heart can't take it

And she might not make it

They say, "Don't dare, don't you even go there"

"Cutting off your long hair"

"You do as you're told"

Tell you, "Wake up, go put on your makeup"

"This is just a phase you're gonna outgrow"

There's something wrong in the village

In the village, oh

They stare in the village

In the village, oh

There's nothing wrong with you

It's true, it's true

There's something wrong with the village

With the village

There's something wrong with the village

Feel the rumors follow you

From Monday all the way to Friday dinner

You got one day of shelter

Then it's Sunday hell to pay, you young lost sinner

Well, I've been there, sitting in that same chair

Whispering that same prayer half a million times

It's a lie, though buried in disciples

One page of the Bible isn't worth a life

There's something wrong in the village

In the village, oh

They stare in the village

In the village, oh

There's nothing wrong with you

It's true, it's true

There's something wrong with the village

With the village

Something wrong with the village

THE HOWARTH FAMILY

When it comes to reflecting on the life of their 26-year-old daughter, Ellery, Holly and Robert Howarth of Holladay, Utah credit one milestone day that changed everything: Thursday, September 2, 2021…

When it comes to reflecting on the life of their 26-year-old daughter, Ellery, Holly and Robert Howarth of Holladay, Utah credit one milestone day that changed everything: Thursday, September 2, 2021.

Before that Thursday, the Howarths knew their only daughter to be a feisty go-getter who “liked to do everything and who was good at everything.” That hasn’t changed. As a young toddler, Ellery loved “typical girly things,” especially the color pink; but she also had mastered the monkey bars by age three, and really loved and excelled at sports and playing with the boys, including her four brothers (Spencer—now 34, married to Casey, William – 23, married to Hannah, Benjamin –20, and Christian, aka “Boo” -- 17). When she was six, her birthday party was made when her best friend bestowed her gift wish—a light saber, which she gleefully ran off with, hollering to all the little girls and gifts she left behind: “You all can play with all the Polly Pockets!”

In high school, Ellery was junior class president and had many dates and boyfriends. After, she went to BYU and served an LDS mission to Guatemala, which she loved. Her going on a mission surprised her dad a little, as Ellery had expressed some concerns with church doctrine over the years. But when she came home, “something felt different.” Holly says she slept in the same room as her daughter the first couple of nights because Ellery seemed so off. She cried all night and seemed so sad that her parents thought she might be sick from exhaustion.

Ellery proceeded in her schooling and with her plans to be a lawyer. A few years later when her brother got married in the temple, Ellery approached her dad, sobbing, saying this was something that would never happen for her. Looking back, Robert says he was clueless and shrugged it off, joking, “Get outta here; I gotta go to bed.” Continuing to build her resume, Ellery went to Texas to get a Masters in Education from SMU and work for the Teach for America program in a Dallas Title 1 school. Back at home in Utah, Holly acted on the rumblings in her heart and expressed to her brother, “Sometimes I think Ellery might be gay.” To her shock, he replied, “Of course she is; I’ve known that since she was little.” Holly asked why he’d never said anything, to which he replied he’d promised his wife he’d never bring it up unless the Howarths said something first. When Holly broke down crying, her brother said, “Why are you reacting like this? That poor girl, she’s the one who’s been navigating this on her own. If you can’t love her for who she is, then let me love her and parent her.” That statement shocked Holly into an entirely new mindset. She felt her maternal instinct surge, and she said and knew, “No, she’s my daughter. Of course I’m going to love her!” It was Thursday, September 2, 2021.

Holly immediately called Ellery, who was about to walk into class in Texas. She said, “Ellery, you know how you always say I’m your very best friend in the whole world? Sometimes, I think you lie to me.” Ellery replied, “What are you talking about?” Holly said, “I’m going to ask you a question and you have to tell me the truth. Are you gay?” Ellery broke down sobbing and said, “Yes, I am.” Then she angrily yelled, “How can you ask me something like this right now? I have class!” Right after class, she called her dad Robert, who’d already been filled in. She began to profusely apologize. He asked why she was saying sorry, and Ellery replied, “Because I’m an abomination.” Robert said, “I just love you.” Her siblings echoed that sentiment, with her brother Benjamin, who was doing home MTC at the time saying he had prayed all day for inspired words to share with his sister, and the words that came were also just how much she was loved. Holly says this revelation unraveled a decade of torment their daughter had been enduring alone. In those early days, after that Thursday, Ellery continuously called herself an abomination, feeling like she was the reason her family “wouldn’t be together forever.” It turns out she had been working hard to get her finances in order, feeling as if her parents would cut her off if they found out.

After that Thursday night, as the truth came out, it set Ellery free. She revealed she’d figured out she was gay right after breaking up with her tenth grade boyfriend, and realizing her mom’s admonitions to “don’t make out, and keep your feet on the floor” were no problem at all if you weren’t feeling those urges for the opposite sex. While her going on a mission had shocked her dad, Ellery revealed that was an attempt on her part to make a plea bargain with God to change this part of her. Her monumental depression on her return was due to the fact that this hadn’t worked--she was still the same. Ellery had beat herself up over the years, internalizing every phrase ever uttered against people like her, including when her mom once found out a girl they knew came out and she said, “Oh, her poor mom.” Or the times Holly used to say, “I have a lot of single friends and they have to stay celibate, so gay people can do the same.”

After that Thursday night, Holly actualized she would never want a life of loneliness or celibacy for her daughter. She had recently gone to lunch with a 68-year-old female friend who had never been married and asked her, “Do you still have hope there may still be someone out there for you?” The friend replied, “I absolutely do.” Holly now says, “Why are we telling these gay children, ‘There’s no hope for you’?”

The night after Ellery came out, she told her parents, “If you leave the church over this, I will be angry at you and never forgive you. If it was true before you knew this about me, it still better be true after… Although it’s not for me right now, because there’s no place for me, I know that my God is good.” Holly and Robert went back with Ellery to visit the people of Guatemala whose lives she had impacted on her mission and they loved seeing the pure love and gratitude the people expressed for their daughter. One particular woman who Ellery had helped find the gospel proudly showed them her temple endowment certificate and is a temple worker now. Holly says, “She felt all that; it’s real. Ellery believed all that. That’s where the pain comes from – her not being able to be who she is and have all that. People will say, ‘Oh there’s a place for her in this church,’ and I’ll say, ‘No there’s not, not right now; she can’t have a girlfriend and be a part of the church. That’s hard. It’s heartbreaking for those who want to remain a part.”

While at BYU, Ellery had begun seeing a counselor for her depression and anxiety who helped her work through her own faith progression, after realizing she would need to weigh the pros and cons of staying in an organization that didn’t support her finding a companion. Up until then, she had tormented herself, battling suicidal urges to take her life by the age of 25 so no one would ever “have to know.” Eventually, the therapist helped her identify the church wasn’t servicing her anymore, and she needed to write down those pros and cons and have a ceremony and burn them and say goodbye. One of the hardest pills for Ellery’s parents to swallow was when she asked them why God didn’t love her, saying, “Why would he make me this way if he knew I’d never be able to return to live with Him?” Since Ellery has stepped away from church activity, she has not experienced any more suicidal breakdowns.

Holly reflects that if she hadn’t had that conversation with her brother on that Thursday and immediately called her daughter, she might not have seen her in this life again. Ellery’s 25th birthday was the following December 18th. But instead, Ellery returned home to celebrate and put on a beautiful new dress and went out with friends. Just before she walked out the door, she told her parents, “I never realized I could be this happy.” Ellery currently lives with her girlfriend of a year, Madeline, and one day looks forward to getting married and having kids. She loves knowing she’ll have her family’s support.

As she prepares to welcome their first two grandbabies this summer (each of the Howarth’s daughters-in-law are expecting), Holly has also been on a faith journey, re-examining her belief system. She’s dug into reading the book, Jesus the Christ, to really try to come to understand pure Christianity. She questions why a church would be called after someone who embraces all, but currently as an institution causes so much suffering as there isn’t a safe place for all. She wonders, “Why is it people would rather die than be who they are—those who were born this way? Sometimes I feel like I’ve been punked… The gospel was always so black and white and easy: ‘Do all these things and everything will work out. Unless you’re gay; then it’s not.’ I’m trying to put the work in, so I don’t feel punked. I’m putting in the effort to get to know the Savior again, so I don’t carry these feelings of anger, sadness and heartache. I’ve used the Atonement in my life probably as much as anyone; I’ve needed it. But I’ve been hurt. I have a testimony, but I’m struggling.”

Robert has maintained his LDS faith with the caveat, “I just have to have a testimony that I don’t know everything, and I won’t while here on earth. I’ve got to take what I know to be true and run with that because I don’t like the alternative.” Both Holly and Robert concur that heaven would not be heaven without all their kids; and Robert says, “Ellery, wherever you are, I will find you.” Holly agrees, “She’s our whole world; she’s everything to us. Nothing’s changed in that regard. But a lot of things have been put into perspective since that Thursday, when everything changed.”

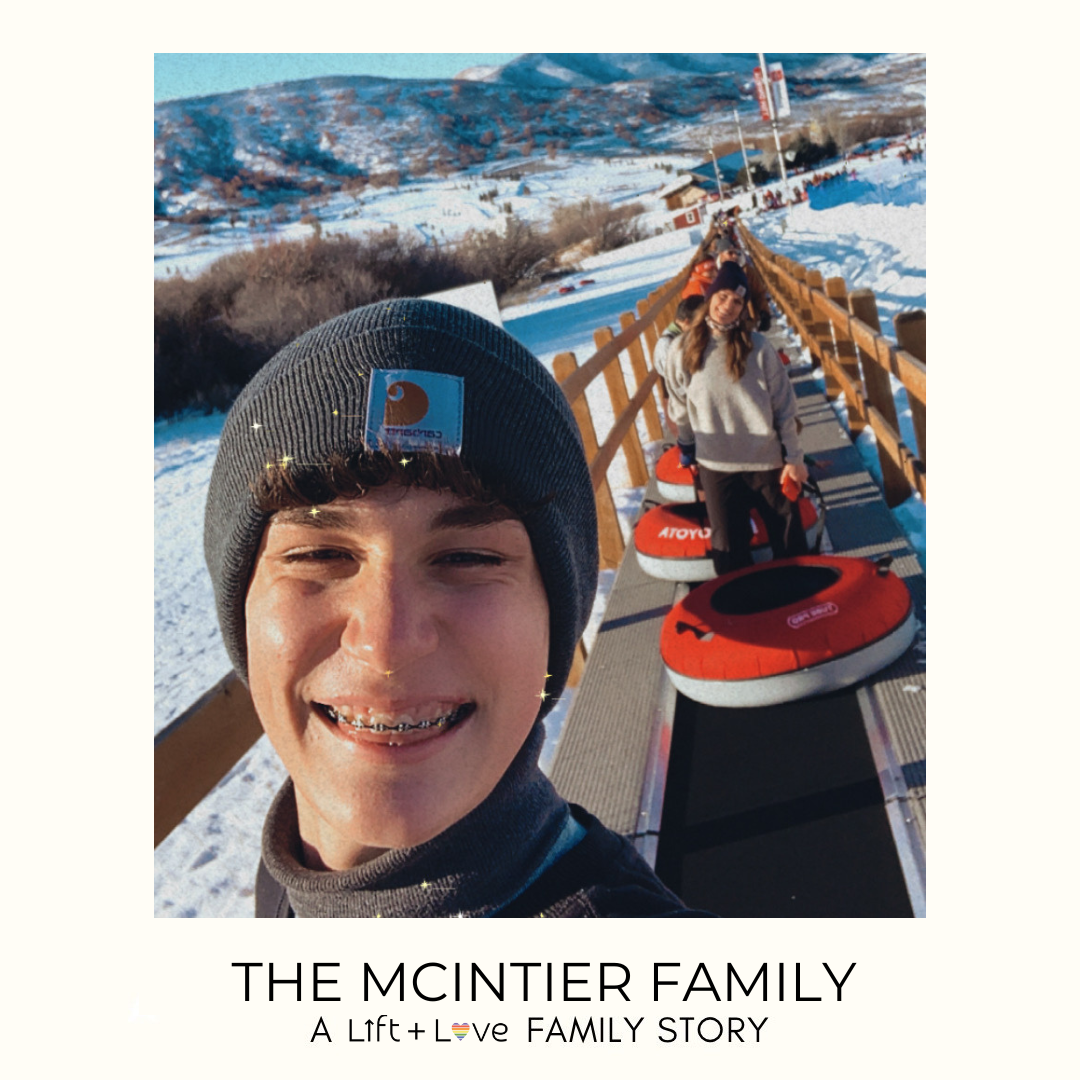

THE MCINTIER FAMILY

Since their oldest son, Max, was a young toddler, Abby and Jeff McIntier always wondered if him being gay was a possibility. But they never wanted anyone to label him before Max himself was ready. Abby says, “In my heart, only he knows who he is. And God.” But, they admit several friends may have wondered.

Since their oldest son, Max, was a young toddler, Abby and Jeff McIntier always wondered if him being gay was a possibility. But they never wanted anyone to label him before Max himself was ready. Abby says, “In my heart, only he knows who he is. And God.” But, they admit several friends may have wondered.

While the McIntiers were in grad school in Buffalo, NY, their close network of friends all had young daughters Max’s age, and he loved playing princesses right along with them. After one particular playdate resulted in a fight (led by Max) over who would wear the Cinderella dress and who would be Rapunzel, Abby’s friend called her and joked, “You’d think this wouldn’t happen with the boy who’s over.” But even at home, Max gravitated toward stereotypically girl things. Abby says, “It wasn’t what I thought raising a boy would be like. My husband and I always thought, ‘Huh’.”

Fast forward to 2015, when Max entered middle school. Abby was about to pop with their fourth child when a friend called and said that one of their kids’ friends had called Max gay, and Max didn’t really seem to know what that meant. Abby thought, “Here it is. I sensed this might come. And I knew I needed to create an environment for him to know he was safe being whoever he is—and only he will know who that is. It’s not ok for anyone else to tell him.” At that time, the political climate was quite negative regarding LGBTQ issues in the McIntier’s Richmond, Kentucky hometown, and middle school can be quite harsh in general, so Abby would often find herself engaging in late night conversations with Max about “so and so in their youth group who’s gay and their parents won’t accept them.” Occasionally, Abby would ask, “Are you?” Max would always reply, “No, I’m not.” Abby would quickly follow that with, “Well you know it's ok, right?”

Finally, in the summer of 2020, Max was ready to come out. He told his dad first, after Jeff said, “You know, if there’s something you want to tell us...” Later with his mom, while sitting on the couch, Max blurted out, “You know I’m gay, right?” Abby nonchalantly replied, “I didn’t, but that’s cool.” Their late night, supportive talks continued into that fall, and one evening, Max was talking about how excited he was to be out, to date someone, to post it on social. Abby felt something inside her want to verbally gush about the prescriptive life her son could have – still in the church, still going on a mission, “the best uncle ever, and he wouldn’t even have to marry a woman!” He could be like a famous performer Abby had known in her younger days as a performer who was now openly gay and still actively LDS (and presumably celibate). Of that night, Abby says, “Max had just turned 16, and luckily, the spirit shoved a sock in my mouth, and I stopped presupposing and just listened. And I realized there’s got to be more to his life than that. I couldn’t tell him to go on a mission so he could go to the temple so he could go to the celestial kingdom and check all those boxes. Call it spirit, intuition, whatever, but nope, something stopped me, saying, ‘That’s not what you’re going to say’.”

The following Valentine’s Day, in 2021, Max decided to come out publicly on social media to mark the one year anniversary of the first time he’d come out to anyone (a close friend). Abby says that everyone saw his post, including a bishop of another ward who’d called Max’s seminary teacher to warn him. The timing couldn’t have been worse. On the very next day, the lesson in seminary was on Sodom & Gomorrah, and it took an anti-LGBTQ direction as “homosexuality” was written on the board as one of the reasons why the lands were destroyed. People in the class compared it to active sins and things like addiction—but being gay was something Max didn’t choose. Friends called Abby who, now pregnant with her sixth baby, was on the treadmill fielding calls telling her that Max had left seminary quite mad. “He felt just awful—so embarrassed.” Abby read the lesson, and then did a deep dive into the Family Proclamation.

She says, “I had my own personal revelations that the proclamation feels incomplete to me. There’s nothing in there that says you cannot get married to a man and still live with God. There’s more knowledge to be received on this subject. I think that Heavenly Father is not withholding info, thinking, ‘Oh, you’re not ready to be non-racist or non-exclusive.’ I believe our biases, cultures, and dogmas stop us from receiving further revelation. We think we get an answer and move on, but there’s probably a lot more that Heavenly Father is trying to tell us.”

Abby emailed the two seminary teachers and the bishop of the other ward who happened to be at that lesson and told them, “Whatever was taught at best was naïve, misinformed, ignorant; at best, it was false doctrine.” Up until that point, both Abby and Max had grown very comfortable with who he was. That seminary lesson was the first time Abby realized her son might be ostracized and considered a sinner for something he didn’t choose. She thought, “There’s nothing wrong with him, and I didn’t like that someone would say that. I turned to Lift and Love and found resources to prove my point that I was right, and that everyone else was wrong… Now, I’m on a journey. I have conversations and sometimes get my feelings hurt. This can be just such a taboo topic.”

Jeff says, “I haven’t always had the best relationship with Max, but thankfully it’s never been because of his sexuality. One time, before he ever came out, I was really pleading to God about what to do about him and our relationship, and I remember distinctly feeling, thinking, and hearing, ‘He’s not yours, he’s mine. You’re just a steward over him for a short time. Your job is to love him.’ I never would have thought that on my own. I think I’m too prideful. But that’s how I know it was from God. All this is not my journey or my story. It’s his."

Shortly after Jeff and Abby had their last baby (their six kids now include Max—18, Perry—15, Nora—11, Freddie—1, Oscar—3, and Charlie Quinn—18 mos.), the McIntiers, who own a couple preschools as well as a dance performance company, were a little surprised when they got a visit from their friend, who now serves as their stake president, and his wife. He was a counselor at the time, and he was feeling out whether she might up for serving as the stake Young Women’s president—with a four-week-old baby. His wife said, “No, don’t do that to her.” Abby says there were probably others in their stake who also might find that appointment jarring. (Abby says, “I’m loads of fun, but rough around the edges. The kind of person who’d wear the t-shirt that says, ‘I’m not drunk, this is just my personality’.”) But Abby accepted the call and continued serving with the youth she’d grown to love as ward YW president. She felt she’d found her niche in encouraging Max and others to invite their friends to church activities—including those who might feel on the margins. Something Max can relate to.

Max has found his crowd in the theatre, and he still keeps in touch with a great group of friends he met in a six-week theatre program last summer. There he met a handful of somewhat closeted kids who live in fear of their families’ responses. Abby says, “I don’t think I’m good at anything, but in hearing about that, I realize I handled this well.” Max is excited to head to the BFA theatre program at Coastal Carolina University this fall. While he usually opts to work at the job “he loves” on Sundays (Dunkin Donuts), Abby says Max will occasionally still come to church with his family because he knows she likes having him there.

Recently, Max attended a sacrament meeting in which someone gave a talk about the law of chastity and temple work. Abby says, “Nothing about LGBTQ was mentioned, just that families can be together through Heavenly Father’s plan.” Yet Abby, as well as their stake president friend who was in attendance, heard and felt what Max and people like him must be hearing and feeling during talks like that. Abby watched Max keep his arms crossed tightly across his chest, triggered. Later their friend acknowledged that while there are so many great things about the church, the way Max must hear things like that is, ‘I will never be enough because of how I was born’.”

Abby jokingly calls herself an agnostic Mormon even though she very much believes in Heavenly parents that we are created in their image specifically. She just realizes there are so many things we don’t know and God may not be exactly how she understood as a child and young adult. “For us to think we know all the things right now and to claim this won’t change, it seems naïve. The eternities are vast – I think this is just a blip.” Abby says people ask her how she does it, how she stays in. When she was 15, her brother passed away and she says that likely out of fear, she decided then to assume the church was true so she could see her brother again. But that experience, along with other family challenges, make it impossible for her to “go back to putting her head in the sand because now, I have such a bigger heart. I think about things differently than the way I was raised. I see all people now more as my peers.” Her family often teases her about her plethora of “gay things” which includes rainbow pins, ribbons, books, etc. she collects to give to others. She says, “I wear the rainbow pin not as a protest, but as a symbol of inclusivity and safety to anyone of the LGBTQ+ community, whether they are out or not. I believe when I bear my testimony, particularly in my calling when working with the youth or leaders, my testimony rings differently, albeit the same, when there is evidence I’m an ally. I want all the youth to know they’re loved, they’re wonderful, and that they matter, are needed, and have a divine purpose.”

In her calling, Abby says she tries to share her personal experiences when she gets asked about things, especially when people present being inclusive as an antidote to “teaching the truth.” She says, “There’s always that clause. So while I’ve thought we might disagree on what the truth is, and my personal revelations might be different than yours, we can all agree we are called to love and not judge. And that the plan is a personal journey between us and God; that’s it. We tend to ostracize and get uncomfortable with people in church who don’t fit the mold. We feel like we have to save them, or they’re evil or done or have crossed that line, and can’t come back. But that takes away our agency and thus makes the Atonement null. Throughout history and scriptures, that’s not the case; Christ died for us all so that all of us can come back.”

THE MARANDA THOMPSON FAMILY

“Did you know?” It’s a question so many parents of LGBTQ kids field, and Maranda Thompson of Kaysville, UT is no exception. She and her husband Jacob didn’t fully know their son Riley, 22, was gay until just last year. But Maranda says they have always known Riley was “highly intelligent and super anxious. He was always very obedient, great in school, a rule follower and so easy to parent. Riley was always a happy, good kid.” Their first inkling about his sexuality occurred when Riley was 14 and admitted to viewing gay pornography. Maranda says, “Looking back, how dumb were we?” Riley began therapy for his anxiety around that time, and Maranda pulled the therapist aside and asked if he thought Riley was gay, wondering “what are we dealing with?” Maranda says, “I love how the therapist didn’t lock him in a box with gender and sexuality at that age but said he might be fluid. And just to wait and see. Looking back, I’m grateful for that.”

“Did you know?” It’s a question so many parents of LGBTQ kids field, and Maranda Thompson of Kaysville, UT is no exception. She and her husband Jacob didn’t fully know their son Riley, 22, was gay until just last year. But Maranda says they have always known Riley was “highly intelligent and super anxious. He was always very obedient, great in school, a rule follower and so easy to parent. Riley was always a happy, good kid.” Their first inkling about his sexuality occurred when Riley was 14 and admitted to viewing gay pornography. Maranda says, “Looking back, how dumb were we?” Riley began therapy for his anxiety around that time, and Maranda pulled the therapist aside and asked if he thought Riley was gay, wondering “what are we dealing with?” Maranda says, “I love how the therapist didn’t lock him in a box with gender and sexuality at that age but said he might be fluid. And just to wait and see. Looking back, I’m grateful for that.”

In high school, Riley enjoyed choir, swim team, and he seemed to like dating girls. But right before he went on a mission, Riley told his mom he might be bisexual. Maranda replied, “When you decide to get married, if you marry a girl, just make sure you’re 1000% in.” Riley replied, “Of course,” and they didn’t speak of it again for the next two years while Riley served his mission in Roseville, CA. A lover of languages and linguistics, Maranda says Riley spoke Spanish “like a boss. He seemed to thrive on his mission – he’d always been the kid in high school who showed up to every youth activity, was 1st assistant in his priest quorum, was super righteous and churchy.”

After Riley came home, he began his schooling in St. George where he studied computer science. After hanging out with his roommates and dating girls for about six months, his anxiety spiked again, which his parents attributed to school, but always wondered… what if? One night, Riley called and again said, “Mom, I think I’m bisexual.” Maranda asked, “Riley, who are you attracted to?” He replied, “Men.” She said, “I’ve been waiting for you to tell me. Riley, I do not support celibacy and loneliness, and I expect an amazing son-in-law. Your dad is waiting for you to tell him, too.” Maranda says, “Of all my parenting moments, that was a good one. But it was the first time in my life that something came out of my mouth that 1000% went against church teachings. But I felt very inspired that’s what he needed, and in that moment, I chose my son over anything else. Our path forward since has been that we choose him; nothing gets in the way of that.”

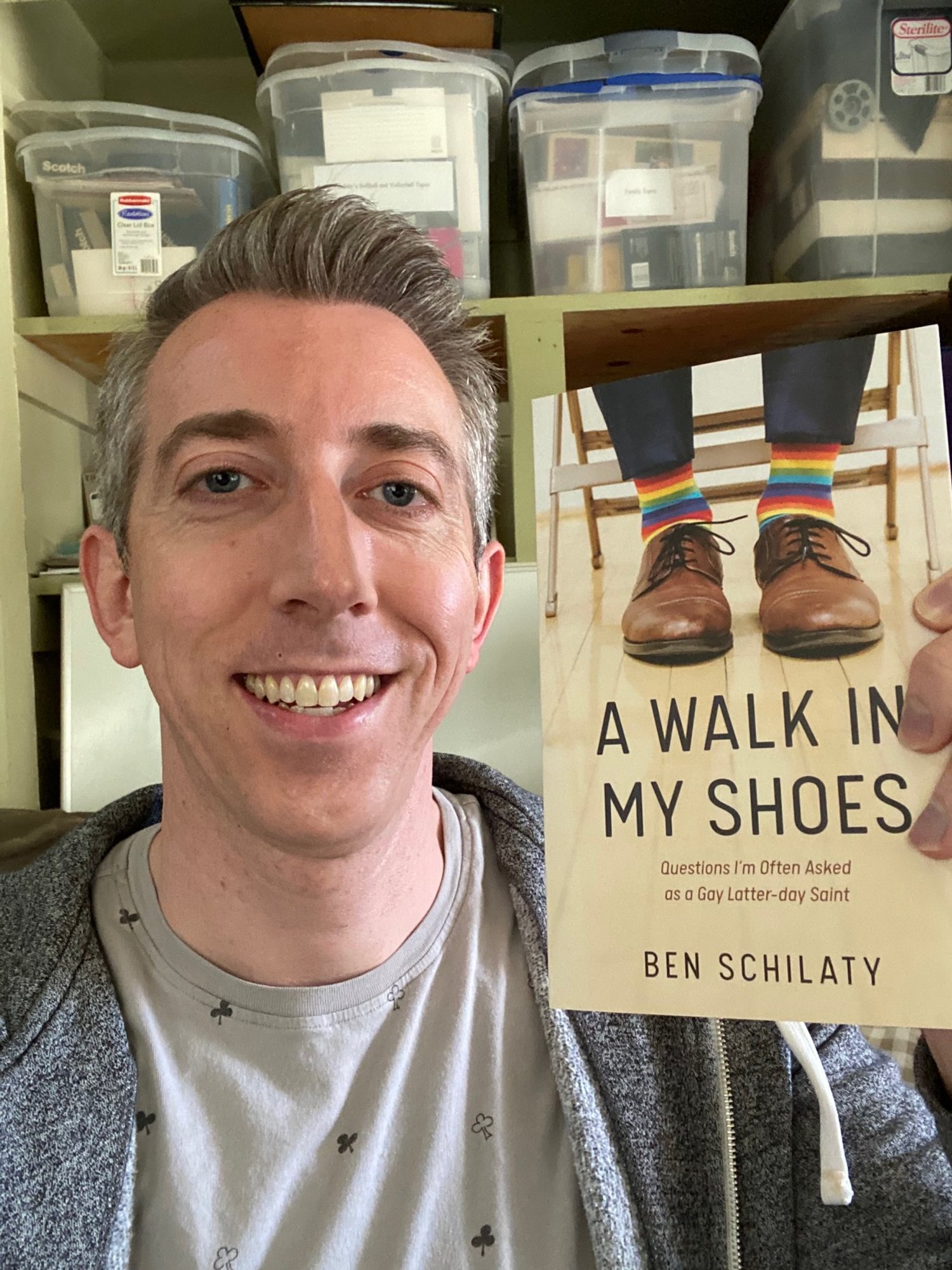

About a month before Riley came out, Maranda’s close friend introduced her to the Questions from the Closet podcast, but Maranda waited to dive in until her son had come out. “That first podcast, everything in me opened up; it was an insane blessing. The work Ben and Charlie are doing is straight from God.” She was excited to share it with Riley and when he listened to it he found validation, love and a path forward. Then, Maranda found the podcast At Last She Said It. “I loved it. It helped me understand and gave me vocabulary for so many things I was feeling as I entered a complete faith crisis. I told my husband, ‘These ladies are keeping me in the church’.” Maranda also found her way to Lift and Love, where she says the early podcasts made her feel “so seen and heard and ok.” The year Riley came out, Maranda logged 22,000 minutes on Spotify, thanks to her podcast grad school education.

Of this time, Maranda says, “This was the most painful, heart-opening experience of my life. I immediately started questioning church. I picked my kid, and thought, ‘What the hell is wrong with the church?’ I went through a grieving process, always wondering am I going to stay? Early on, in my soul, I felt that not everyone can stay, but if everyone leaves, it won’t get better. I felt I could be one of those people who could stay. I’m not sure how, but I think I can, and I’ve tried to hold on to that.” Maranda feels her own faith crisis has contributed to her ability to bond with Riley, who has been very open with his parents. “As he shares his feelings going through this, I’m able to understand what he needs and where he stands spiritually.”

Maranda says if their kids want emotional support and comfort, they come to her. But if they want logic, reason and great solutions, they go to their dad. “I tell Jacob he’s the best gay dad ever to which he replies, ‘Stop calling me gay dad.’ But Jacob’s my hero. He’s kind, stalwart and straight forward. A few weeks after Riley came out, he called us panicked and said, ‘I don’t know what to do next.’ Jacob said, ‘Well, go on a date.’ and followed up with practical and loving advice. After we hung up, I said ‘How’d you know what to say?’ And he said, ‘I just told him what I’d say if he was dating girls!’ I was like, ‘Oh, ok, that makes so much sense’!”

Maranda had moments where she was scared how people might treat Riley, that the world might be unkind. When he decided to room with a bunch of fellow returned missionaries at Utah Tech, she wondered if he needed his own room. But she laughs that he replied, “Mom you are so old.” She’s relieved that his generation is “so accepting, they’re cool with it…” Maranda says people her age have also been wonderful. They seem to be committed to saying, ‘Ok, we’re going to do this better than our parents did’.” Maranda says, “My faith in humanity has gone through the roof.”

Under her own roof, came the moment in which each of Riley’s three younger brothers would find out he was gay. Tyler—18, was a senior at the time Riley told him and he seemed surprised at first. Maranda said, “Think about him in high school.” And Tyler (the ”cool, ASB kid”) laughed, “Yeah! He was the token gay kid, with all those girlfriends. And he made cakes. Mom, do you know how much street cred I’ll get for having a gay brother?” Slightly younger and more aloof, Noah—16, was “a bit clueless even though we’d been talking about it around the house for months. One night I said, ‘Noah, you know Riley’s gay, right?’ to which he replied, ‘What? Mom, you have to tell me things. Wait… does this mean Riley has to leave the church’?”

Maranda says, “That’s so sad that that’s the message we’re sending. I told Noah that whatever path Riley took, we’d support and continue to honor his personal revelation.” The Thompsons youngest, Dallin—10, who can be “mouthy, funny” has taken to gleefully weaponizing the word homophobic in a humorous way around the house. All the Thompson brothers love and support Riley, and while Tyler now gets a little flack on his mission (in the Dominican Republic) for having a gay brother, “he can handle it.”

One of the most dissonant moments of Maranda’s life were the months between Riley coming out in February of 2022 and Tyler getting his mission call in April. “I spent those months in faith crisis, supporting one gay son and mission prepping another. On Riley’s mission, I’d written him letters full of quotes by prophets—I was so adorable. When I write to Tyler, I focus on loving those he serves and building a personal relationship with Christ—I just can’t with prophet quotes right now.” She says reading Brian McLaren’s book, Faith After Doubt, calmed her soul. Maranda says she was “brutally honest” in her recent temple recommend interview. When she talked to Riley about it, he said, “Mom, I can’t say those things in an interview.” Maranda replied, “But your mom can!” Tyler jokes that Maranda had better hang on to her recommend in case she needs it when he gets home. Jacob has never entertained the idea of leaving the church and is also fully supportive of Riley and what he needs to thrive and be happy. Maranda feels kids need more black & white thinking when they’re little, but “they get a free ticket into nuance when they are ready if their parents are nuanced.”

Riley says he doesn’t regret a single thing about his mission and still goes to church, although it has become very difficult (“He’s always loved God so much”). He did ask to meet with a therapist this summer to process religious trauma. Maranda says Riley attends Encircle and has found that the general consensus among his peers there is that those who are openly queer do not last in the LDS church. Riley’s been dating and still feels comfortable going to the temple. Maranda says, “He calls himself the most emotionally well-adjusted gay man he’s ever met.” After he returns from a date, he’ll joke with his mom about the “trauma bond” he and his fellow gay male date shared, and she’ll ask, “What was his trauma level?”

“Every time we talk about his dating, Riley thanks me. He is often astounded by the way other parents have responded to their LGBTQ children. He says, ‘You and dad being the way you are has made it so much better. All my queer friends want to meet you and hug you.’ I reply, ‘All we said was find a good husband. He knows we’ve got him, church or not. Whatever he needs. He’s such a great human.”

Maranda believes representation matters. As a junior high math teacher, she loves when her students recognize her low-key rainbow jewelry, especially when they complement it in a way in which she knows it also means something to them. Last June was her first Pride month knowing she had a gay son, and Maranda noticed how much it meant to her to see rainbows everywhere. “I realized, that was one more place that is safe for my son. That home, that business, that family is safe, they get it.” Every week, she shows up at church with her rainbow bag from the REI outdoor Pride line, and recently, a friend stood up from across the chapel to show Maranda a large rainbow bag of her own. “It meant so much. She doesn’t even have a dog in the fight; she’s just all about love.” After Maranda mentioned her feelings about seeing rainbows to her therapist, the next time she showed up for a session, she was touched to see a framed rainbow art piece hanging on the wall.

Maranda calls her town a bit of a Mayberry and says people do try really, really hard to be nice—including the “good, kind, loving” people of her ward who she says all love Riley. They have sat through a few uncomfortable lessons at church, one in which someone said you can’t fly a Pride flag or pay for a gay wedding. Afterwards, Maranda met with the bishop (who she calls the kindest person on the planet) and told him they could do better. He then prepared a talk and sent it to her to prescreen, in which he outlined all the good, supportive things church leaders have said about being kind and loving toward LGBTQ people.

Of her journey, Maranda says, “I thought I was a loving person, but had no idea how much more I could love. It’s been a wild ride… I took this year to learn and calm down-- just get to a place where I could start listening and teaching with patience. Recently, I had a conversation with an older man in my neighborhood in which he expressed some hurtful views about LGBTQ and I put my hand on his arm and gently said, ‘You know my son’s gay? The way you’re saying things is so hurtful.’ This transitioned into a 20-minute loving conversation led with courage and love and understanding, where six months ago, I was so fearful and hurt. I’m getting there – getting to a place where I can be an ally and be useful in this space. I’m ready.”

THE AMANDA SMITH FAMILY

On weekday mornings, Amanda Smith of Rancho Mission Viejo, CA can often be found guiding a quiet room of clients through a yoga practice, encouraging them to bend, breathe, and just be as they sort through the stresses and traumas that can bring one to child’s pose—a position she has often needed to fold into herself…

On weekday mornings, Amanda Smith of Rancho Mission Viejo, CA can often be found guiding a quiet room of clients through a yoga practice, encouraging them to bend, breathe, and just be as they sort through the stresses and traumas that can bring one to child’s pose—a position she has often needed to fold into herself.

Amanda’s oldest child, Lynden (now 11), was diagnosed with cancer at age seven in 2019, and luckily survived after a six-month battle of chemo and radiation. In 2020, shortly after Lynden was pronounced cancer-free, Amanda’s mother tragically took her own life, after battling mental health struggles. After processing each of those immense trials during the pandemic, Amanda felt it was time to undergo certification to be a yoga instructor as well as finally reckon publicly with her orientation—something that until now, she had largely eschewed in an attempt to please others. But with remarkable strength, the married mother of three has learned to exhale, and summon the desire to share--if only to make the path slightly less difficult for her fellow sojourners.

Amanda Smith was raised in Idaho and then Minnesota during her teens, where she was surrounded with a conservative mindset both in the church and with her family. They didn’t attend church much, but made it very clear that it was not okay to be gay. Amanda thus grew up in a state of shame, always feeling like “something was wrong with me,” as she had sensed she was attracted to girls from a young age. Of her teen years, she says, “I tried to overcorrect. I had all these boyfriends and was actually quite mean to people who I found out were gay or lesbian—like some sort of defense mechanism.”

When she was 19, Amanda told her family she was gay and would not be hiding it anymore. They refused to meet her girlfriend of nine months at the time said they wanted nothing to do with having a gay child. While living with her girlfriend and another gay male friend, Amanda said she assimilated to “an awesome LGBTQ community” and “finally felt I was being true to who I am.” While Amanda says that felt so good, looking back, this was a sad time because of the guilt and shame she carried and the fact that she couldn’t maintain a relationship with her family who believed this was “just a stage” for Amanda because she had had several boyfriends in high school when she was trying to be something she wasn’t. She’d been raised in a house where she was continually reminded by her mom, “I just want you to marry a nice Mormon boy.” Through this, Amanda maintained a testimony, but it came with “so much guilt and shame.” She started making dangerous decisions and spiraled to a dark place. But once she hit rock bottom, Amanda found her legs and knew she needed to make some changes.

Amanda moved to BYU approved housing where she could start a fresh life on the “straight” and narrow, trying to pass as straight in her newfound anonymity. She wanted a relationship with her family and the church again and felt those both were impossible if she dated women. She’d had several leaders pound in the point that, “As you get closer to Jesus and make correct decisions, it will get easier over time.” Looking back, she now acknowledges they may have meant well, but had no idea or experience in what she was dealing with. She tried to date a few guys in Provo which only made her feel like she’d rather end up alone.

At that time, a family friend casually mentioned she had a brother in California, and she thought he and Amanda might get along. The friend knew of Amanda’s past of dating women, which at the time Amanda outwardly played off as a phase or that she was bi. She says, “I let them believe what they wanted to.” Amanda met the brother, Dan, and something sparked. The two started dating. Eventually she moved to join him in California.

She says, “This was the first guy I’d ever dated who I thought, ‘I really like this person’. My sexuality aside, I knew he was an amazing person.” She thought she could make it work. Dan knew of Amanda’s past with women, but was willing to look past that. So they decided to tie the knot and set up shop in southern California. Four years into their marriage, right after their second child, Ledger (now 9), was born, Amanda became consumed with the thought she was lying to her husband. One night they went out to dinner and she told him, “This isn’t a phase. I’m lesbian—queer.” Dan replied that he figured, and that as long as she wanted to be with him, he didn’t care. That was an aha moment for Amanda, where she finally for the first time felt a brief respite from the shame and self-hatred she had carried for so long, after trying everything to change this part of her. “I’d married a man in the temple, had callings, had leaders say, ‘It’ll get easier as you grow closer.’ But nope, this is who I am.” Amanda has continued to battle those feelings of shame and in the past year, she’s put in a lot of healing work to try to come to a place of full self-acceptance.

Taylor Swift’s song lyric, “Shame never made anyone less gay” played through Amanda’s head as a mantra, and she decided she didn’t like this elephant in the room. She was tired of sweeping it under the rug. She’d have moments where she’d come out to a close friend, and it would make her so emotional she’d started crying. She hated how she’d tried so hard to have this taken away, but she just couldn’t change it.

It was about this time that Lynden was diagnosed with cancer. Amanda says, “During that time, things were so hard—it was terrible, but I had a distraction and didn’t have to think about myself. I got to shelf it for awhile.” After Lynden finished treatment, Covid hit and two weeks into quarantine, Amanda got the devastating call about her mother’s overdose. As the national political fervor also swirled, headlines thrust LGBTQ issues in Amanda’s face, and friends and family often shared their negative views of LGBTQ people while around her. It got to be too much--everything on her shelf came crashing down.

In 2022, Amanda told her husband she needed to open up and publicly share that she was in a mixed-orientation marriage with a man she loved, but her attractions toward women were still an undeniable part of her identity (though she has never pursued an interest in anyone else since being married). The nudges continued, and Amanda started coming out publicly on her social media feed, which had garnered a significant following prior when she had shared the details of Lynden’s cancer treatment and her mother’s death. Adding the words “in a mixed orientation marriage” to her Instagram profile did thrust Amanda in the court of public opinion, and she faced naysayers on all sides. Some friends and family really struggled at first, assuming this meant she was leaving her family and the church. But they’ve since seen nothing’s really changed, now they just know this about Amanda. Some in the LGBTQ community also criticized her for not living “an authentic life,” by choosing to stay with her husband and in the church. And some parents reached out to ask Amanda to speak to their gay kids to try to promote mixed-orientation marriages as an ideal option for their kids, to which she’d reply, “It’s not what I’d prescribe.” She recognizes that Dan is one of a kind, saying, “Most won’t find a spouse who is super loving, supportive, and doesn’t need them to be super sexual. It’s hard. Even for me, who has an awesome marriage and partner, it’s still so hard.” She acknowledges that if she had been a young adult now in today’s climate, some of her decisions might have been different. She appreciates that her bishop and Relief Society president both reached out with support and said they’d have her back if anyone gave her trouble.