lift+love family stories by autumn mcalpin

Since 2021, Lift+Love has shared hundreds of real stories from Latter-day Saint LGBTQ individuals, their families, and allies. These stories—written by Autumn McAlpin—emerged from personal interviews with each participant and were published with their express permission.

DR. GREG PETERSON

Dr. Greg Peterson spent the first month of this summer in an empty house, sleeping on an air mattress, and shopping at Kohl’s for his day-to-day wardrobe needs to start his new job. He didn’t know when he moved to Salt Lake City that he’d be arriving a month before the moving truck with all his belongings. But he chooses to look on the bright side, saying: “We’ve got air conditioning, running water, Wi-Fi, a couple barstools, and we’re together. It will all work out. It’s an adventure.”

Dr. Greg Peterson spent the first month of this summer in an empty house, sleeping on an air mattress, and shopping at Kohl’s for his day-to-day wardrobe needs to start his new job. He didn’t know when he moved to Salt Lake City that he’d be arriving a month before the moving truck with all his belongings. But he chooses to look on the bright side, saying: “We’ve got air conditioning, running water, Wi-Fi, a couple barstools, and we’re together. It will all work out. It’s an adventure.”

It's a life the Greg Peterson of ten years ago never anticipated possible: living in a committed relationship with a man he loves in Utah, where he has recently been named the president of Salt Lake Community College. The new job position surprises few, considering Greg’s longtime academic career passions and success. But a self-described “late bloomer in the love department,” it wasn’t until Greg’s late 30s that he allowed himself to finally explore the need to accept his orientation and pursue a relationship.

Growing up in Oregon City, Greg was always an academic. As a young student, he loved to sing, draw, play soccer and most of all, read. When Greg entered adulthood and became a first-generation community college student, he had an opportunity to teach ESL to adults who’d migrated to the States and saw up close how much they were able to improve their lives because of language acquisition. Greg’s eyes opened further when he worked in a furniture warehouse for a summer, “which was horrible but I had to,” and met co-workers who would have been doctors and professionals in their home countries but were stuck in difficult, menial jobs. These bonds inspired him to try to provide opportunities for all, with education as the change agent. Greg felt this could best be done by pursuing a career in the community college space.

Greg went on to earn a bachelor’s degree in English from BYU, a master’s in adult learning from Portland State University, a doctorate in educational administration from the University of Texas Austin, and an MBA from Kaplan University. As he studied, he initially worked as an ESL teacher, but gradually began to move into administration roles. Selected as an Aspen New President Fellow and recently recognized as East Valley Man of the Year by Positive Paths, throughout his career, Dr. Peterson has led key efforts in student learning and success that have impacted over 100,000 students through developing transfer partnerships and college promise programs at various institutions as well as launching the first community college Artificial Intelligence program in the nation.

Now recognized in his field, there was a time when one of Greg’s superiors noticed things weren’t going so well. While employed at Long Beach City College, Greg was battling dark emotions and trying his best to keep his personal life separate from the professional, as he’d done for decades. Feeling deep duress and isolation one night in which he was contemplating taking his life, he decided to call his parents. He wasn’t able to voice the source or extent of his despair on the phone, but the time and nature of the call concerned his parents and he felt it. “The worry I would hurt them if I were to do something made me think differently. That was a turning point to accepting this part of me.” Greg’s boss at work had also noticed something was off, that Greg wasn’t the happy, open person he’d once been. Greg says, “I came out to him, and he was really supportive.” That led to the beginning of Greg’s coming out journey.

Throughout his many years as a rising academic, Greg had been used to “living in my head,” so he had heretofore turned off his emotions and tried to stay there to avoid it all. He says, “I tried to be as obedient and as Christlike as I could be. All that emotion—the natural man—I tried to keep it locked away.” He recalls times in hiding in which people would ask him how his morning had gone, and he’d shut down and find himself debating whether it was safe to say what he’d had for breakfast. “I was managing everything, so worried about people finding this out about me and how bad I was.”

Finally one day, Greg decided to turn to God, and says he “really prayed.” In return, he says he felt God’s love and the divine confirmation that he was ok. After coming out to his boss, Greg wrote a letter to his parents, then told a couple brothers, then a couple friends in a “really slow process” in which Greg says, “I felt like I needed to know all the answers so I could answer all the questions I might get asked. I didn’t want to get pinned down and not know where I was, nor do or say something that would be held against me later or harm others. It took me longer to accept that where I am today might not be where I am tomorrow. I felt like people wanted me to be static, but that’s not how life works.”

The past few years reflect the opposite, with active changes for Greg. He remembers taking a survey at last fall’s Gather conference in which respondents were asked if five years ago, they knew where they’d be today on a scale of 1 to 5. Greg says he was in the 1 territory of never anticipating he’d be in a relationship or moving to Utah. But now, he’s in a wonderful live-in relationship with his formerly long-distance partner after making the move to accept the promotion at Utah’s top community college. It was a job interview process that also revealed how far things have come, as Dr. Peterson was able to openly talk about his own personal relationship as he expressed his commitment to honoring the best interests of the diverse student population at SLCC as both gay and a member of the Church.

Greg also stays active by working out at the gym almost daily, and he still loves to sing. The former college where he worked offered a Broadway music solos class that Greg took a few times both to observe student perspectives and for a chance to sing onstage himself. At one semester-end concert, he took on “You’ll Be Back” from Hamilton. Over the years, Greg’s also loved to sing in church, saying, “It’s one of the things I like best about going.”

While Greg maintains a belief in God and trusts the church is “a tool of our Heavenly Parents to guide us back and feel their love,” he says, “I don’t know that the church knows where I fit or has a place for me right now.” To expound, Greg says, “The church wants me, but not the full me. There’s an expectation I’d have to sacrifice parts of me to become like the Savior, and as a disciple, I believe this is true, but I can’t draw nearer to my Savior by sacrificing this authentic part of me. I can’t do that.” For now, Greg is most interested in focusing on walking with the Savior, day by day. Similar to the patience he embodied while waiting for the moving truck with his furniture to finally arrive (and it did), Greg says, “I can’t think about where I fit in the eternities in our church, but I do know that my Savior will provide a way for me, and I don’t have to have all the answers. I’ll just keep moving forward, trusting Him as I navigate where I feel His love, and where I need to be.”

THE DAVIS FAMILY

“All great spirituality is about what we do with our pain. If we do not transform our pain, we will transmit it to those around us.” This was the Richard Rohr quote TeriDel Davis opened with at a recent presentation at an ally night in her Gilbert, AZ hometown. Joined by her husband, Tad, TeriDel then passed the mic to their 17-year-old trans daughter Kay to expand on the pain she thought she’d be able to bury until after high school, when it might be a better time to “figure it out.” But Kay explained, “This didn’t work out very well for me, as the only way I could bury the pain was to try and make myself numb to (it).” Citing Brene Brown, she continued, “When you numb your pain, you numb your joy.”

“All great spirituality is about what we do with our pain. If we do not transform our pain, we will transmit it to those around us.” This was the Richard Rohr quote TeriDel Davis opened with at a recent presentation at an ally night in her Gilbert, AZ hometown. Joined by her husband, Tad, TeriDel then passed the mic to their 17-year-old trans daughter Kay to expand on the pain she thought she’d be able to bury until after high school, when it might be a better time to “figure it out.” But Kay explained, “This didn’t work out very well for me, as the only way I could bury the pain was to try and make myself numb to (it).” Citing Brene Brown, she continued, “When you numb your pain, you numb your joy.”

The desire to teach their kids to pursue rather put off joy is what has propelled the Davis family to share their journey.

For TeriDel, the import of the call to be Kay’s mother started while she was pregnant with her oldest and being set apart for a calling. After the standard calling-related language, TeriDel was given specifics about the child she carried, that she would “find being his mom hard because it would be very difficult, but if I raised him unto God that he would then bring me the greatest joy I would ever know.” Anticipating her child would be born with severe special needs, TeriDel was surprised when Kay was born a healthy, happy newborn. As a toddler, Kay proved to be quite advanced, demonstrating high intelligence. But as she continued to grow, TeriDel says it was indeed difficult to raise and connect with Kay. The Davis family learned Kay was autistic, which propelled TeriDel to adjust her parenting style so that she could better connect with and teach Kay.

When Kay was baptized at eight years old, her parents felt immense joy and gratitude that despite the challenging years, they had gotten to a good place and that Kay was “a kind, loving, smart kid who had proven very dedicated to pleasing her Heavenly Father.” About five years later of growth opportunities for the family, which now included younger siblings Gibson aka “Gibby” – now 16, Langston aka “Badger”—14, Cliff—12, Lilah—9, and an older foster child, Cynthia, Kay asked if she could talk about something that had been weighing on her. She wanted to know if TeriDel thought her younger brother Gibby had ever shown signs of being gay. TeriDel initially was upset Kay had asked this, thinking Kay might be agreeing with the school bullies who had been teasing Gibby for some time. She firmly replied that they’d had many conversations with Gibby and his therapist and that he wasn’t gay and that these kinds of questions were hurtful to Gibby.

The conversation initiated several months of heated conversations between TeriDel and Kay about LGBTQ issues, until one day, Kay approached her mother and again asked the same question about Gibby. Upset at her persistence, TeriDel turned from the dishes she was washing to scold Kay but saw a pained look in her eyes. TeriDel replied she needed a moment before she could answer. She went to her room to pray, where she was prompted that Kay was asking these questions about herself, and that TeriDel needed to become okay with Kay being gay or transgender very quickly and go talk to her about it. TeriDel says, “It was made very clear to me that Heavenly Father would not be okay with me doing anything other than loving Kay and supporting her.”

TeriDel called her husband Tad at work, who concurred. She then called Kay into her room and point blank asked her if she was gay. Panicked, Kay mumbled in return that no, but she was experiencing feelings of gender dysphoria. TeriDel had to ask what that meant. Tad explains, “It’s like you don’t even know the questions to even ask until you have to.” He explains that over the next several months in their research, things would come up that proved unsettling to his theretofore reliance on binary, black-and-white church doctrines. “It was unsettling in the sense I thought I could put everything in the right place on the bookshelf. But this was like someone had knocked over the whole shelf, and some of the books on the floor I didn’t need anymore, and I realized I needed some new books, too.”

While this was the first time they were able to talk about it as a family, Kay had been quietly battling complex thoughts and emotions for sometime privately. When returning from a family party with cousins on her 13th birthday, Kay sat in the back of the family van pondering her reality and future. Asking herself questions about how she might avoid typical teenage pitfalls and drama, Kay identified that she’d never felt an attraction to boys and thus must not be gay, nor did she desire to get into a romantic relationship as she felt “I’m not very romantic, impulsive, or charming.” A new question emerged: “Am I trans?” A sense of dread settled in as Kay realized she could not say no to this, as she had never been comfortable being labelled, grouped with, or seen as a boy. She preferred to be known by other labels such as “smart, creative, kind.” This new thought induced terror as Kay presumed her firmly conservative Christian family would hurt her mentally or emotionally if they found out—which is why she shrouded her initial questions about the topic as a concern about her brother. But Kay says, “Without any guidance, I could never come to an answer.” She had searched on social media, but struggled to find anyone who likewise didn’t see being trans as a testimony-breaker. As the sun set in the horizon outside the van, she knew it was time to pray and ask God her question: “Am I trans?” The answer she received was “not a declaration of my identity but just a comforting message that, ‘either way is okay’.” Kay says, “It was in that moment that any worry of God’s judgment or wrath dissipated, and while it didn’t answer my original question, it released a weight I didn’t realize I was carrying. It seemed like my inner conflict was much more manageable with the knowledge of God’s love for me.”

The new knowledge of her daughter’s identity and struggles opened TeriDel’s eyes to a heightened awareness of how she had been getting all her information “from straight people” and “somehow thought I had an accurate view on what would cause gender dysphoria.” She also realized how hard church can be when harmful rhetoric about the LGBTQ+ community is shared. While in the temple and privately she relied on the spirit to personally guide and direct her to a state of joy and enlightenment in her journey, it became difficult to hear comments like that of one woman in Sunday school: “The fastest growing tool of the devil is suggesting that having tolerance and love for other people means that we should be supportive of people who don’t follow the gospel. We need to rid the church members of any behavior or persons that prohibit us entering the temple.”

While Kay has not gone public with a social transition yet, not wanting to deal with the social or political consequences, she has found herself in many uncomfortable situations in which she has struggled with anxiety, deep pain, and fear of rejection. Even after initially telling her parents, Kay says she didn’t really know how they felt for a while as it took them time to be more open to talking about it. “They didn’t know how painful it was to sit and wonder who I was all by myself, especially because it had been much easier to ignore and sideline it.” She has also experienced a state of stasis and abstract dread, as if feeling stuck in a swamp. Even her favorite hobbies like art projects can feel like hopeless wastes of time. Kay credits conversations with her mom and an excellent therapist for helping pull her out of these funks.

TeriDel says with her new lens, church has become a hard place for her with the “random comments and misguided lessons.” She’s uncomfortable in any calling other than serving in the nursery, and is grateful that having a relationship with God has remained the priority of Kay, saying, “Hopefully we’ve helped her understand as long as she has that relationship with God either in or out of the church, we’re ok with that.” Tad often finds himself reflecting on Joseph Smith’s adage to “teach them correct principles and let them govern themselves,” deferring to prayer and personal revelation and his belief that God judges us on a curve tailored to us.

Church can be unwelcoming at times according to Kay, “though our ward does its best to be welcoming and respectful, which is appreciated.” It meant a lot to Kay while attending seminary last year that she had a teacher who was inspired to gently answer the prescient question, “What should I do if I feel what the spirit is telling me and the teachings of the church contradict?” The teacher said that when Kay is conflicted, she should continue to make that a conversation between God and her, and to continue to pray about it until she feels peace. Kay says, “I think it’s hard for my seminary teacher to understand how much his answer meant to me. That answer allowed me to let go of my mental image and went leaps and bounds in allowing me to feel more comfortable in seminary. It even meant that when the lesson turned to the topic of how we must treat LGBTQ individuals with kindness even if we don’t approve of them, that I could at least be in that space and rely on my own personal answers to prayer.” Kay continues, “Even though it stings to hear that I am the person they don’t approve of, I believe that at some level my seminary teacher believes that God knows me and accepts me as I am.”

When their son, Gibby, recently asked why the nature of God seemed to change so much across different books of scripture, Tad explained that explaining the grand plan of God would be like explaining all the complex levels, tricks, lore and Easter eggs of his favorite video game to his five-year-old cousin and expecting her to understand. TeriDel says, “That is what God is dealing with. He has this amazing, beautiful, complex, and fulfilling plan, and then he goes to his children (who are metaphorically five-year-olds) and tries to explain things to them and then has to deal with whatever they thought they heard. So it’s not surprising that God might sound a little different over time. God is limited by us.”

While Kay remains grateful for her reliance on personal revelation in discovering her own identity, TeriDel is increasing appreciative of a Christ-centered perspective and the grace and love that has come into her life by “not worrying about all of that stuff and just focusing on the very basic principle of showing love to those around me. In the end, God’s plan is just love.” Tad appreciates how their close-knit family, in which their kids are all each other’s best friends, can now have healthier conversations about the long term because they trust Kay to make good decisions for herself. He says, “Kay is such a good kid and has always wanted to be a good person and do her best to make her Heavenly Father and Savior happy. I’ve realized I needed to take a backset and trust she’ll make good decisions. She’s proved us right.”

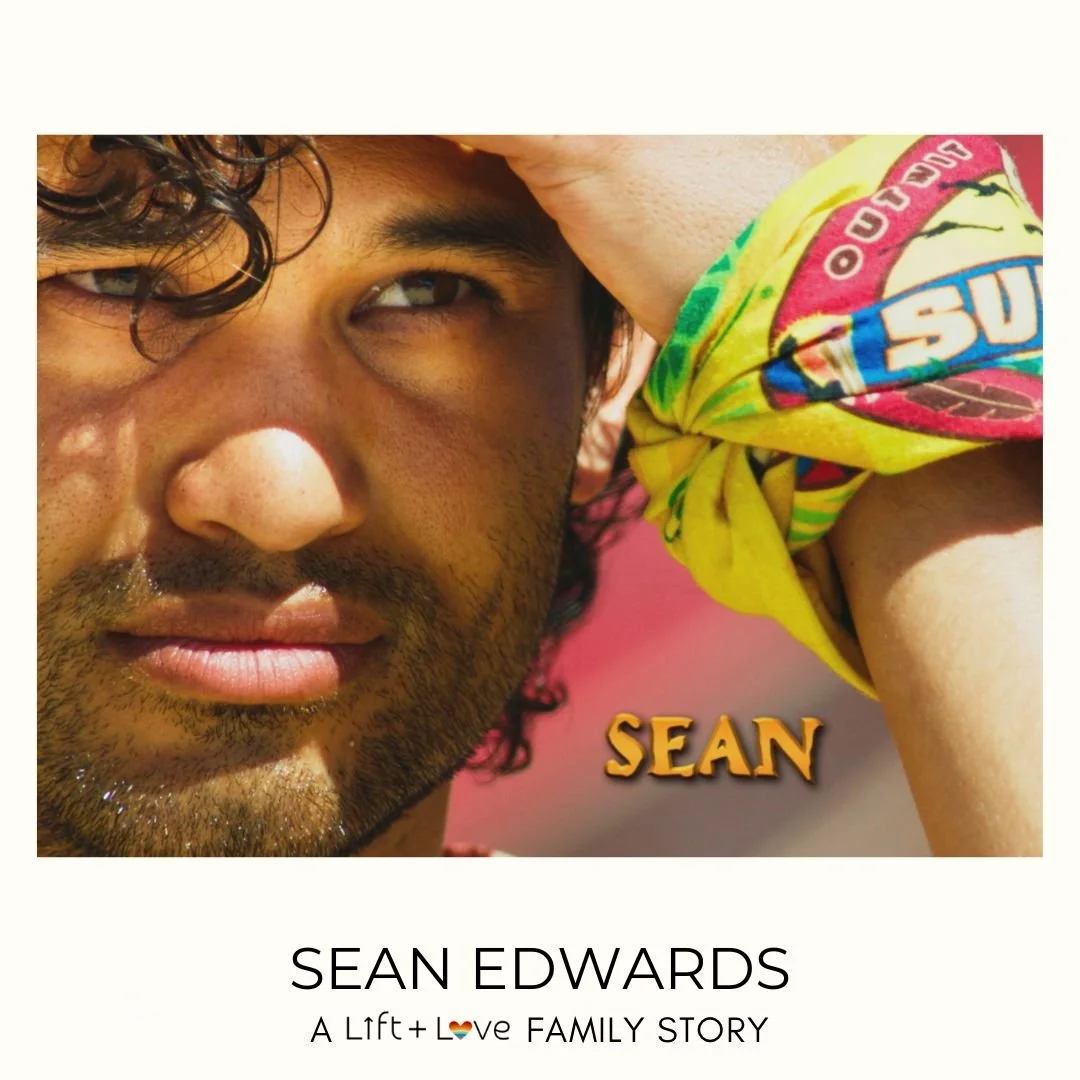

SEAN EDWARDS

Being voted out of your tribe is rarely the goal. But sometimes when difficulties arise, people elect to leave on their own. Such was the case for amiable, Provo-based elementary school principal, Sean Edwards, whose recent stint as a contestant on CBS’s Survivor Season 45 was cut short when he nominated himself to leave early after just four episodes. Originally a player on last fall’s most defeated tribe in Survivor history, the “Lulu Tribe,” after some initial setbacks, Sean moved to the opposing “Reba” tribe where he admitted he was ready to be done with the game at tribal council. While Sean later expressed regret at his decision to leave prematurely, he remains a huge fan of the show, and now with hindsight, honors the initial intention he had as a competitor looking to reclaim lost time—time he used to spend trying to be something he wasn’t…

Being voted out of your tribe is rarely the goal. But sometimes when difficulties arise, people elect to leave on their own. Such was the case for amiable, Provo-based elementary school principal, Sean Edwards, whose recent stint as a contestant on CBS’s Survivor Season 45 was cut short when he nominated himself to leave early after just four episodes. Originally a player on last fall’s most defeated tribe in Survivor history, the “Lulu Tribe,” after some initial setbacks, Sean moved to the opposing “Reba” tribe where he admitted he was ready to be done with the game at tribal council. While Sean later expressed regret at his decision to leave prematurely, he remains a huge fan of the show, and now with hindsight, honors the initial intention he had as a competitor looking to reclaim lost time—time he used to spend trying to be something he wasn’t.

Sean grew up in New Jersey, the son of a Chinese mom and a Caucasian dad. He greatly admires his younger sister, Krista, and his older sister, Elaine--who has autism and cannot live independently. As such, the family moved from their western state roots to settle in the Princeton, New Jersey area for his father’s work and the excellent healthcare facilities for neurodivergent individuals.

Growing up, Sean always relied on the solid foundation of trust he had with his parents, believing they had his best interests at heart. But he was terrified in high school to tell them he was gay, especially after an LDS friend from California he’d met on Myspace revealed when he shared the same news with his parents, they’d kicked him out of the house. But Sean’s mom quickly assured him they would never do that. She promised they would “figure this out together,” and Sean felt willing to follow her lead. While she expressed her love, Sean remembers two emotions surpassing the others that day as he could tell she felt sad and worried. He asked that she be the one to tell his dad, who Sean was afraid to disappoint, as the only son in the family. Rather, Sean recalls his father didn’t overreact, saying, “He is pretty pragmatic, but it took him time to process.”

The three decided to keep Sean’s news just between them as they considered the best next steps. His parents dug into what limited resources there were at the time and came back with a solution: conversion therapy. Or seemingly, therapy that seemed promising as it was led by an LDS man who claimed he had “overcome his gayness through a particular process.” Sean says, “As someone who’d grown up living the typical LDS lifestyle, I wanted more than anything to be straight, so I tried it, beginning at age 17.” He endured the therapy off-and-on for another five years, which he says ultimately engrained in him “that I needed to change a fundamental part of who I am to be considered good and kind and accepted by God and others. It messed with my mind, trying to seek approval from God by trying to change who I am.”

BYU Provo proved to not be a cultural fit for Sean. He was called into the Honor Code Office at one point and put on probation for a year because someone had snapped a picture of him at a gay club in Salt Lake City, where he would go dancing. “I needed that community of people like me so badly.” That trauma resulted in him swearing off all gay clubs in Utah out of fear. He remembers another time of being especially hurt when, as his ward’s gospel doctrine teacher (a calling often assigned to people like him working toward teaching degrees), he found out a selection of his peers came to his class and sat in the back just so they could make fun of his charismatic mannerisms and animated disposition. He had experienced something similar before – having been bullied in middle school and high school where people called him the f slur and one time, threw a garbage can at him and called him “gay trash.” But now, at “the Lord’s university,” it felt like his tribe had spoken. Sean says, “It was really unfortunate to think that people who were part of my community were attending my Sunday School class to make fun of me.”

Back home in Jersey, his two best friends from high school, Ivana and Shannon, had the opposite response when, after his freshman year of college, Sean came out to them. “They were so supportive of me being gay, but when I told them I didn’t know what direction this was taking me because having been raised LDS, I wanted to do that path, they were like, ‘Why? You’re gay; be authentic to who you are’.” Sean says, “It was such a diverse perspective from the first time I’d come out to my parents. I was glad they didn’t have the LDS lens so they could help me understand the full spectrum of support I needed.”

As Sean proceeded with his schooling, which culminated in him graduating from BYU and then, while simultaneously being a high school vice principal, earning a doctorate degree from the University of Utah where he did his dissertation on LGBTQ+ students and perceptions of connectedness in school communities, Sean realized that his experiences being marginalized had also led him to developing resilience, empathy, true compassion to others, and had provided him a growth mindset in which he could choose to be confident while also looking out for others who suffer along their way. They are all gifts that have helped Sean buoy the young students who now walk the halls at the school where they call him Dr. Edwards, their principal.

“Living in Orem and working in Provo as a public-facing person can be tricky. There have been multiple occasions where people have called the school secretary to express their concerns about their kids having a gay principal. It’s difficult because I love the students I work for and want them to have incredible experiences learning math, reading, STEM, all those great things. It’s hard to have people question my integrity.” Because of this fear, Sean didn’t come out to his professional peers until after he was working in an administration position.

Nowadays, Sean sees being gay as a huge blessing. Not only did his life story of navigating the challenges of being LGBTQ+ in a conservative religion contribute to him being selected to be a contestant on his favorite show, but he appreciated the fresh air Survivor island gave him to completely be himself and meet new people in a context in which he didn’t have to assume they were going to call the office on him. He says, “Even though it’s a competitive environment, the humanity is still there. I made really meaningful connections.” The bonds he created with all the players still linger via a vibrant, 18-person text chain, and Sean laughs that one of his closest friends from the show, Sabiyah, is a lesbian and Black former Marine turned truck driver from the south. He says, “We’re worlds apart in life experience and upbringing, but she became my #1 ally and best friend out there.”

However, the greatest gift being authentic has allowed Sean was meeting his husband on Facebook back in 2016, because “Who meets in real life these days?” Sean laughs. Matt also grew up in the LDS faith tradition, one of seven kids from Draper, UT. The two instantly connected. Their first date was a scary movie, and one of their initial connection points was their shared love for you guessed it: Survivor. (Matt had auditioned previously.) After a year of dating, Sean made it clear that he’d be ready to get engaged, and Matt proposed not once, but twice—the first time via a scavenger hunt around Provo guided by meaningful clues leading to places that meant a lot to the two of them, and then, very publicly onstage at a Naked & Famous concert in Aspen, CO, where Matt had pre-arranged with the band to be called up for the big event. They were married August 1, 2018 in Orem, and bought their first house together a year later. Matt now works for the U as a researcher for K-12 issues across the state, where he crosses paths with many professors from Sean’s graduate program.

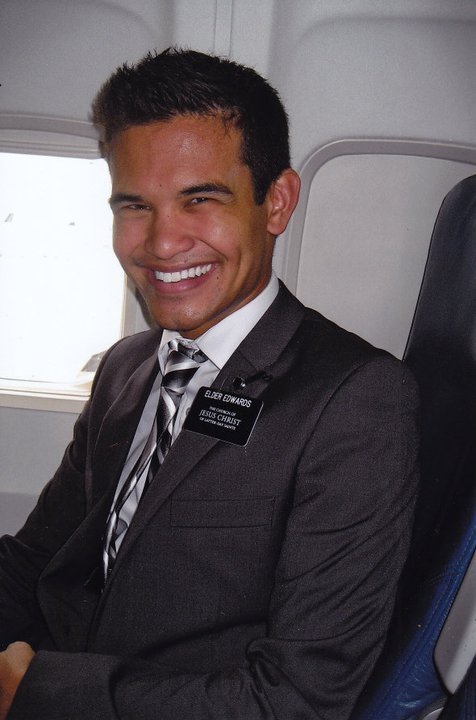

While the two no longer participate regularly in the LDS faith, Sean loved his Las Vegas mission (where he had the opportunity to connect with several members of his dad’s side of the family), and will now occasionally attend a friend or former student’s mission farewell or homecoming church service. He says he and Matt are “very consistent” in their daily prayer: “Having a strong relationship with our Heavenly Father and Jesus is important to us.” Affected by the positive and not so positive influences of the church community within which they were raised, they choose to bring aspects of their faith into their relationship, though try to create a safe space with their spirituality. At 5’6, with “not an athletic bone in my body,” Sean remembers not fitting into his ward youth group’s frequent basketball nights. If he could pass along any lived experience to church members and leaders, Sean says, “I wish church leaders knew how to love LGBTQ+ people. I’ve heard so many say that the decisions I was making were wrong or bad, much more than I’ve heard the message, ‘I love you’ or ‘The Savior loves you’. As LGBTQ+ people who grow up LDS, we know the church position on LGBTQ+ topics; we don’t need leaders reminding us again and again. What we need to know is our leaders and Heavenly Father and Jesus love us. I think because they tell us how we live is wrong or bad, they think it’s an expression of their love for us, but I want to be so clear in saying it’s not. You might think that, but if it’s not being received in that way, it does not resonate and is not a message of love.”

Luckily, Sean and Matt are able to fill their lives with the friends and family they love and who love them, which are plenty. Living so close to Matt’s family, who Sean says he adores, they see many local family members often. Sean believes he will also frequently continue to see members of his Survivor family. “I absolutely loved my Survivor experience. It was fun, inspiring, complex, challenging, beautiful—every emotion wrapped into one experience… What’s so interesting though is how it became this great metaphor for my life in general. I had prepared for years and years and wanted it for such a long time, since I was 11 or 12, but never had the confidence to try. Then, in 2020, I started submitting applications and after three years, got on. I had all these dreams of what might happen, but my tribe lost nearly every challenge and I did not win the game. And that’s life, you have all these expectations and convictions of how life will go, but it can go the opposite. Even though it’s not what you might have thought it would be, it can be beautiful. I wouldn’t be who I am today if I didn’t go through all the experiences I did, and it's the same with Survivor.”

Sean admits that he wishes he could have approached the moment of his departure differently, but after not eating anything but coconut and papaya (having no fire) and experiencing difficulty sleeping for nine days, “I wasn’t firing on all cylinders.” He concludes, “Sometimes we’re human, sometimes we make mistakes, and sometimes it’s on a national platform. I didn’t have to leave; I could have lived out my dream. But instead of allowing regret to drive me, I need to find a way to own it and learn valuable lessons from my mistakes. We must have the resilience to move forward.”

While he may not have ultimately won at Survivor, Sean was asked to emcee this June’s Utah PRIDE parade, where he recruited his husband and sister Krista to join him. As part of his celebration, he went to a Salt Lake City gay club for the first time since his BYU days, which he says, “felt like a reclamation. I’ve decided, I’m going to do me.” Having recently turned 36, Sean says if he could go back a couple decades to that teenage boy who dreamed about being on a reality competition show, he’d give him some valuable advice: “Prioritize connections with people who matter; find your tribe. You will be successful, happy, and you’ll find partnership and companionship. You won’t be lonely. It’s ok to take risks, try new things, and embrace failure. Who you are is beautiful.”

Photo credit CBS

Photo credit Robert Voets/CBS

Selected photos courtesy of CBS and Robert Voets/CBS, as noted above

DAN McCLELLAN

For all those who’ve used The Word as a weapon against the LGBTQ+ community, it’s time to holster your Bibles and go on social media. There, you’re likely to encounter the reel-explanations of Dr. Dan McClellan, aka @maklelan, where nearly a million followers on Tik Tok, Instagram and Twitter tune in to find out what the Bible actually says, from an actual Bible scholar. Dan explains there is a difference between a theologian, whose work is to teach how a religious group should incorporate or interpret Biblical teachings, versus a critical Biblical scholar, whose job is to evaluate and explain the historical and social context of the actual written work at the time it was written. Dan says studying it this way removes the common proclivity to consider the Bible as univocal—meaning the text speaks as one universal voice and thus can’t disagree with itself, as all parts should harmonize with the others. This deeper study brings to light the need to consider data over dogma, which is exactly what Dan now does with his online break-it-downs and popular podcast, Data over Dogma…

For all those who’ve used The Word as a weapon against the LGBTQ+ community, it’s time to holster your Bibles and go on social media. There, you’re likely to encounter the reel-explanations of Dr. Dan McClellan, aka @maklelan, where over a million followers on Tik Tok, Instagram, YouTube and Twitter tune in to find out what the Bible actually says, from an actual Bible scholar. Dan explains there is a difference between a theologian, whose work is to teach how a religious group should incorporate or interpret Biblical teachings, versus a critical Biblical scholar, whose job is to evaluate and explain the historical and social context of the actual written work at the time it was written. Dan says studying it this way removes the common proclivity to consider the Bible as univocal—meaning the text speaks as one universal voice and thus can’t disagree with itself, as all parts should harmonize with the others. This deeper study brings to light the need to consider data over dogma, which is exactly what Dan now does with his online break-it-downs and popular podcast, Data over Dogma.

The problem with dogma, according to Dan, is that it can be painful for certain populations like the LGBTQ+ community when exclusive ideologies are favored by the power structures that find them beneficial. This social identity politicking underlies so many of the philosophies and interpretations Dan started to see floating across the social media landscape around 2020, when he decided to put his degrees to work online to join the conversation. When it comes to the scholastic frames hanging on his wall, there are four of them—including a bachelor’s from BYU in ancient Near Eastern studies, a masters in Jewish studies from the University of Oxford, a master of arts in biblical studies from Trinity Western University, and a doctorate from the University of Exeter, where Dan defended his thesis on the cognitive science of religion and the conceptualization of deity and divine agency in the Hebrew Bible in 2020. Along the way, he’s become well-versed in 12 languages. When people like to challenge whether he is really a “scholar,” he laughs, and insists that dealing with so much negativity is actually job security.

Biblical scholarship was not a job Dan envisioned until he began his Biblical Hebrew studies at BYU and thought, “If I could make a living out of studying the scriptures, that would be the coolest thing in the world.” He was not the typical BYU student. Raised in West Virginia, Maryland, Colorado, and Texas, he was not brought up particularly religious, and in his late teens, made several friends in the LGBTQ+ and other marginalized communities while waiting tables. Dan joined the LDS church at age 20, and quickly realized he brought along a different world view than many of those raised with “the primary answers.” For instance, he understood evolution to be true, that the earth is not a mere 6,000 years old. He was always fortunate enough to find himself around other likeminded members of the church, even if they were in the minority.

He served a mission a year after joining the church and there says he found himself “compelled to be a representative of a more conservative perspective. At the time, I was willing to toe the line, but it never sat well with me.” Afterwards, he observed that conservative-mindset population multiply at BYU, where most of his peers had a very black-and-white, binary view of the world. He hoped to find more nuance, more compassion and charity for those who got the proverbial short end of the stick. And then he met the Soulforce Equality Riders, who in the vein of the Civil Rights’ Movement Freedom Riders of the 60s, were a group of young people who went on a seven-week bus tour to protest discrimination against LGBTQ+ students on college campuses. This was something Dan could get behind. Knowing people who had family members and friends who’d taken their lives because of oppression from church and the broader conservative community due to their orientation and gender identity, Dan got in touch with Soulforce and asked them to come speak at a gathering at his apartment complex which included several student wards. He felt this was work that mattered.

Dan met his wife at BYU and as they began to raise their three daughters, he further contemplated what kind of world he was bringing his children into. When his oldest daughter approached him at age seven and asked, “What sports are girls allowed to play?” Dan acknowledged that was a question he’d never had to ask as a boy. “But the fact that had occurred to her already, and she had accepted it, brought me to tears. I knew I needed to do more to try to change the world for the generation we’re raising. I couldn’t be on the sidelines.”

This was 2016, around the time where Dan was deeply troubled at the seemingly mass acceptance from his Utah-based community of a political candidate who proudly boasted about sexual assault. The fact that this wasn’t a deal breaker for voters, and the peripheral surge of homophobia in the political space, ignited something in Dan, who then says he “chose to put my privilege on the line and speak up for those who didn’t have accessible privilege.” He became the Democratic party’s precinct chair for Herriman, UT from 2016-2020, was the Salt Lake County Chair of the LDS Democrat Caucus from 2018-2020, and ran for the Utah House of Representatives in 2018 and the Utah Senate in 2020. He didn’t win either race but impressively minimized the blue-red margins. Along the way, he clearly let people around him know he would be speaking out against the hostile actions he was witnessing to let people in minority communities know he was safe, saying, “If my work makes some feel uncomfortable, then good.”

As the pandemic of 2020 continued to incite and divide the country, Dan decided to peek into the Tik Tok space to see what people were sharing. He was surprised at the amount of religious chatter; this was a conversation he had a right to and interest in joining. “I saw a robust community talking Bible and religion from all sides—from very conservative Christian and Jewish creators to those styled as deconstructionists and those overcoming religious trauma. But I didn’t see a lot of credentialed experts. I thought I might be able to position myself not to join anyone’s team, but to call balls and strikes when I see them. To my great surprise, there was a lot of interest.”

When it comes to data vs. dogma, Dan says, “If there’s a dogma I stick with consistently, it’s that all other things being equal, we should give the benefit to the less powerful group. It’s interesting, the fact that doing this infuriates so many people who explain why it’s ok for them to hate… When people challenge my bias recognizing how power structures govern so much of the world around us, and why so many experience the world so differently from someone like me, that’s why I work at the intersections, trying to amplify women, immigrants, LGBTQ, and root out Islamophobia and Antisemitism.”

Dan has worn a Pride-themed watchband for years that his wife bought for him because “he likes colorful stuff.” (A talented sketch artist, he’s also an avid comic book character fan.) He tells those who ask that he wears his watchband as a signal that he’s hopefully a safe space and is going to stand up for people who are often disenfranchised. Interestingly, over the ten years he recently worked for the LDS church as a scripture translation supervisor, he’s worn it in meetings with members of the Quorum of the Twelve when he was often brought in as a Bible expert. “I never got one word about my watch… It's interesting the people who run the church haven’t rejected my expertise, when people on Twitter have so much objection.”

The evangelist community gives Dan the most heat online, and he feels is the largest foe right now to the LGBTQ+ community as many are “inserting their dogmas into the political sphere.” He's always been impressed (though not surprised) by the amount of atheists, agnostics, “none’s” and deconstructionists who follow and laud his work, but occasionally an atypical fan presents themselves, as was the case when someone recently recognized Dan in a grocery store and confessed not only was he in the extremist group DezNat, but he’s also a Dan fan. “I didn’t see that one coming,” laughs Dan.

Having traveled all over the world for his career and seeing the church operate everywhere, Dan is often asked his views on a variety of Bible topics. He has a project in the works via St. Martin’s Press entitled, The Bible Says So—a book that includes the greatest hits of Dan’s social media, with each chapter taking on a different claim of what the Bible says about abortion, Jesus as God, homosexuality, the mark of the beast, etc. As Dan’s online presence has grown, it has become his number one focus and income source, though he still occasionally teaches online courses, and currently has an honorary fellowship with the University of Birmingham Cadbury Centre for the Public Understanding of Religion.

As to what the Bible says about homosexuality, Dan says, “It’s a reflection of where their societies stood at the time and what they understood about sexuality. And it’s different between the Old Testament and the New Testament, based on the ideas of social hierarchies or domination.” He explains that the ancient concepts of gender and sex don’t line up with our concepts today if you allow them to operate on their own terms. “Early Judaism talks about six or seven gender identities, some that could line up with trans and nonbinary. Early Christianity was more conservative and still doesn’t line up perfectly. Everything in the Bible represents a certain framework and set of conventions that are much different from today. Pretending what people said 2,000 years ago ought to be authoritative today gets tricky when it comes to their unflinching endorsement of buying, selling and owning other human beings—it puts the lie to anyone who claims to fully subordinate all their interests to the biblical texts.”

Dan continues, saying, “You have to ask, what are your priorities and agendas with the interpretive lenses you bring to the text?” In regard to structuring power, he says you’ll come up with a certain set of conclusions if you prioritize that over loving God and loving your neighbor. “The Bible is a story about the transition from an insular small group to the whole world. For Christians who read it to understand everyone to be if not a child of God at least their neighbor, they should see it’s about maximizing the success of the whole group, not our domination over a certain group. If people read the Bible and find a God who loves all, that should be the priority. But human nature often retreats to prioritizing the protection of one’s standing and access to power.” But Dan argues that the Bible teaches us to fight against human nature to put what God wants above what we want. “If your Bible is telling you to do the opposite, you should reevaluate your faith.”

Concluding that many Biblical teachings are “outdated, harmful, and have long been irrelevant,” Dan says, “But people have turned their opposition to homosexuality into an identity marker for the social identities important to them. They leverage what the Bible says to authorize and legitimize that identity marker to structure their power and values in favor of their identity politics.” A point Dan reiterates “so often that people are probably sick of it” is that “everyone negotiates with the Bible, so much so that what it actually says is no longer relevant in terms of social monitoring. Polygamy, slavery from the start of the book until its end, the objectification of women—we’ve jettisoned it all as it no longer serves our social identities. I think the Bible-induced homophobia will ultimately go away just like slavery. It’s just a question of how long it will take for people to prioritize children’s safety.”

Dan pointed out that evangelical scholar Richard Hayes (who wrote a book in the 90s that took a hardline stance against homosexuality) will soon come out with a new book in which he claims he was wrong and now argues from a theological point of view for full inclusion of LGBTQ+. Dan recognizes that his first book did a lot of harm for which Hays has not yet had to face accountability, but anticipates more and more people will come around in the future. Dan closes out his own book with the fact that again, “Everything is negotiable. As more people realize they know people who are LGBTQ+ and choose to respect and love them, there will be no choice but to negotiate those prejudices out of our lives.”

Here are some of Dan McClellan’s videos that we especially recommend:

https://www.tiktok.com/@maklelan/video/7375917733050977582

https://www.tiktok.com/@maklelan/video/7369580573762850094

THE JOHNSON FAMILY

Cameo and Cooper Johnson knew they wanted their children to have a different kind of upbringing: one that expanded outside of Mesa, Arizona, where they were both raised. As such, after marrying, they took their four children, Cora-now 23, Granger-21, Jonah-19, and Ezra-15, for most of their young lives to live in various parts of the world. These travels were not always luxurious—rather, the family worked hard all year to save and sometimes barely broke even as they moved about--living and learning with the locals along the way…

Cameo and Cooper Johnson knew they wanted their children to have a different kind of upbringing: one that expanded outside of Mesa, Arizona, where they were both raised. As such, after marrying, they took their four children, Cora-now 23, Granger-21, Jonah-19, and Ezra-15, for most of their young lives to live in various parts of the world. These travels were not always luxurious—rather, the family worked hard all year to save and sometimes barely broke even as they moved about--living and learning with the locals along the way.

They lived in Guatemala for four months, where they were involved in various service projects including distributing food to locals for Christmas, building a sustainable tilapia pond with and for their branch president, and assembling stoves for indigenous villagers so the residents could have warmth and a way to cook food. In Petra Jordan, their young son gave his own shoes to a barefoot indigenous child whom he had befriended, after learning that the children there don’t have the opportunity to go to school but must work in order to provide support to their families. In Spain, they met an artist on the street without arms who drew beautiful works of art with his feet and inspired their young son to overcome all obstacles. In downtown Philadelphia, they often passed unhoused residents in the streets to walk into church, and on a fast Sunday, later watched as those same people from the streets entered the building as well and bore the “most gorgeous testimonies” after which their fellow congregants (many of whom were new to the LDS faith) would shout out “Hallelujahs” and “Amens.” In Cambodia, the Johnsons lived with a local family. “Ten of us shared the same pit toilet bathroom without plumbing or hot water and had to pour cold water on ourselves to bathe,” says Cameo. “While there, we were invited to the funeral of the village leader and also invited to be blessed by a Buddhist monk. We honored these other traditions and beliefs. We were constantly exposing our children to other spiritualities and ways of thinking with love being the unifying focus.” This experience happened during the senior year in high school for their eldest child, Cora, and Cameo largely credits the priority on family closeness and emphasis on Christ-focused service and doctrine through their travels rather than building a social network as the reason each of her four kids have chosen to cling to the gospel in which they were raised. “Because we were only in many of our wards and communities temporarily, we didn’t worry about ostracization… and once we returned to Utah and Arizona, we really saw the diversity of the places and people we’d met with such unique needs and wants than what I’d understood growing up.”

On June 1st of this year, the family traveled together to California, where Cora married her girlfriend of over a year, Ady, in a beautiful ceremony in the Redwoods, near where they had both met while serving as LDS missionaries. The two were never companions, but after admitting to having feelings for each other on their mission, they put those feelings aside to focus on serving until they came home. The service was simple, only attended by their parents and siblings. Cora’s returned missionary brother had received a ministerial license to perform the nuptials. Cameo says as the simple ceremony was just “focused on them, we didn’t have to worry about the extraneous. It was beautiful.” She continues, “Both families had come a long way in the last year to process, change, and grow, but because we all know them and what beautiful humans they both are, you can’t help but see the genuine love they have for each other and desire their well-being and happiness. Their pure love is just evident on their faces.”

A week later, the couple had a reception in Flagstaff near the Johnson’s home, in which there was a bounty of music, dancing, acceptance and love. It was a party attended by many family members and friends from near and far, including many from the girls’ missions who they had served. “It was a happy, happy time,” says Cameo, “and because they chose to already be married by the time people arrived at the reception, there were no worries about feeling judged. It was already done.”

While such a warm reception to the marriage of two females from the LDS faith may come as a surprise to some, it was no surprise to Cameo and Cooper when Cora finally came out as queer at age 16. “We always knew, and had had conversations between us as a couple since Cora was three or four years old, like, ‘Hey, what are we going to do if she tells us she’s gay or that she wants to be a ‘he’?” says Cameo. Cora previously shared her own story on Lift & Love, and her mother Cameo concurs her daughter never fit the gender norms as a child. People gave her dolls she didn’t want, and she cried every time she was told to put on a church dress. When she’d play house with her fellow school girls, Cora always cast herself in the role of “husband.”

When she was younger, Cameo admits she didn’t know anyone in the queer community two decades ago and was quite fearful of what might happen due to how she had been raised, saying, “Anything new is scary for me.” But through many conversations, Cooper assured Cameo that they could just wait and see, that they didn’t need to anticipate everything right then. So a decade later when Cora finally came out, Cameo was not a bit surprised or scared as she’d had a decade to work on her own feelings. She says, “I felt comfortable because I knew who she was—the most kind, nonjudgmental person I’ve ever met, and I’ve met a lot. This is Cora—she’s not sinful or someone who cares more about herself and material desires. She’s a very spiritual person, making It hard for anyone to continue in any preconceived notions about the community. Because I know her worth and value and how amazing she is, and had been prepping for ten years, it wasn’t hard for me. I know I’m lucky in that regard.”

What did worry Cameo a bit was that when Cora came out, in the same sentence, she said, “I’m gay and I want to stay in the church and go on a mission.” Cameo had experienced enough of their Arizona culture to know how the church at large perceives the LGBTQ population, but she also chose to respect her daughter’s decision and support what she needed to do. Cameo again figures that the family’s emphasis on core principles of Christ-centered living is what drove Cora to see the divine purpose in serving a mission for a church that would later not allow her marriage in their temple.

Cameo also reflects on the efforts they had made to create a safe space in their home when Cora was a young child after they witnessed a neighborhood child who was perceived to be gay often be referenced by derogatory slurs, including in their own home. Cameo sat down one of her young children who had repeated the word and in very certain terms, made it clear, “That is not a word we use, because people are born this way—lovely, beautiful, and often more kind and gentle than the rest of us. We have something to learn from them, and I never want you to say anything that would make us seem better than them. We all have differences.”

When Cora later came out, she told her mother she remembered that experience and knew her home would always be a safe space. Cameo reminds parents, “Our children are always watching us, including our interactions and the phrases we say. It’s important we remember that they are listening to the jokes we laugh at. Our kids are watching, and determining whether we’ve created a safe space for them to later become whoever they may be.”

While the Johnsons traveled, both Cameo and Cooper pursued their masters’ degrees. Using her training as a Psychiatric Mental Health Nurse Practitioner, and after selling their first mental health practice, Cameo recently started a new one called Ponderosa Psychiatry in Flagstaff. She has found that by word-of-mouth referrals, she largely serves individuals at the LGBTQ+ and LDS intersection, including those serving or having served missions, and those who love them, to help them have a place to process their thoughts and emotions. “There’s an intersection between how we love and how we’re told we’re supposed to love and obey that can come across as not very loving to our children… It’s important to remember that incongruence is much more fabricated than our spirits and bodies believe. Love is love, and we know that in our hearts. When we don’t feel we’re being loving or when we’re being judgmental, it doesn’t feel right.”

Cameo again credits her family’s unique life experiences and current luck in having a very supportive bishop and stake president, who both came to Cora’s and Ady’s wedding reception, as part of the reason they’ve been able to join their kids in their desires to serve and stay in the church. She says, “I love my bishop and stake president. I have had leadership in other areas of the world who weren’t so understanding, but I’ve come to understand that they don’t define my relationship with Heavenly Father and Jesus. It’s just me; there’s no intermediary. Those people are called for a reason, but are also humans struggling with the human experience, and I’m ok with that. That’s the beautiful thing about the church—personal revelation. I love having my direct line.”

Read Cora’s Lift+Love family story here

Wedding photo credits to Anna Naylor Photography

IESE WILSON

After earning two degrees in music performance, Iese Wilson, 30, now holds his dream job as a high school choir director. The conductor role he’s assumed in advocacy work has also proven a dream come true for many of his LGBTQ+ Latter-day Saint peers around the world who have benefitted from his efforts…

After earning two degrees in music performance, Iese Wilson, 30, now holds his dream job as a high school choir director. The conductor role he’s assumed in advocacy work has also proven a dream come true for many of his LGBTQ+ Latter-day Saint peers around the world who have benefitted from his efforts.

But it first took Iese (pronounced eeYESeh) years of coming to terms with his own identity as a gay believer in his faith, which ultimately happened in a prayer in which Iese was told he was to come out to his family and to also help take care of the LGBTQ+ population at BYU Hawaii, where he was a student. At first, he argued with God, feeling this went against everything he’d been taught. But when Iese pulled out his patriarchal blessing “to prove God wrong,” he read words in a new light that confirmed his life mission would include full-time ministry work in this space.

It all started with a church talk he gave at BYU Hawaii in 2019, when he was 25 years old. While speaking about faith, Iese felt prompted to come out to his ward. Some students approached him afterwards about starting a support group, which led to him helping create the first LGBTQ+ support group for members off campus. Iese anticipated he might be bullied for these efforts, but that didn’t happen. Instead, he had people coming to him left and right, eager to confide and share the isolation they’d experienced, with desires to build community. “It was mind-blowing how many there were who needed to connect. I realized I had to do something about this.”

Over a couple years, Iese says an estimated 200 people reached out to him for support from across campus and from around the world via social media, including those hailing from the Phillipines, Samoa, Fiji, Taiwan, Japan, Tonga, areas of southeast Asia as well as those in the United States. Often, Iese would agree to meet with the students in secure locations, as so many of them were experiencing intense fear under Honor Code policies. Iese organized these stories and compiled a summary of the experiences of 36 students (while protecting their identity), and shared the document with BYU Hawaii’s President, John Kauwe III. He was blown away by the university’s president support and desire to learn more. A globally renowne researcher on Alzheimer’s disease as well as a recently called Area Seventy, President Kauwe was someone Iese found highly impressive. Iese was further impressed as President Kauwe looped university VP Jonathan Kau into the conversation. Together, along with the support of Iese’s uncle and stake president Kinglsey Ah You, Iese was invited to organize the university’s first LGBTQ+-themed fireside.

Having seen their video about being supportive parents of a gay son (and BYUH alum) named Xian on the LDS church website, Iese reached out to the Mackintosh family of Utah to see if they might be willing to zoom in to speak at the fireside. They happily obliged. In the days leading up to the event, Iese was also asked to sit on the panel. As he shared his desperate plea for students and faculty to consider how they could improve inclusion efforts, he looked out in awe at hundreds of students, many of whom he recognized as closeted students who never anticipated feeling this kind of support at the university. It was a powerful moment for Iese, after years of navigating powerful feelings.

Though he didn’t have words for it, Iese first knew around age 10 he was different from his peers. After attending elementary school each day in Garden Grove, CA, Iese would join about 15 cousins at his grandma’s house, where he felt like the “odd one—the loner, the reader.” He’d listen as his older cousins and kids at school talked about their crushes, and wonder why he was drawn to boys. When he attended a summer camp for Hawaiian kids right before sixth grade, he was terrified to see he’d be expected to shower in a restroom with a “tree of life showerhead situation.” He begged his counselors to not have to use the group shower, horrified of what might happen. But he didn’t have a word for it until middle school, when Iese first came across the word “gay.”

It was around this time that Prop 8 ballot measures were surging in California. While his family was less active in the church, Iese absorbed that if he were to be the “good Mormon boy” he was trying so hard to be, he needed to adopt the homophobic rhetoric he witnessed some of his peers and youth leaders vocalizing as they advocated against gay marriage. He says that, “Seeing the protests in front of our temples was an outward expression by society of what I was experiencing as a gay person in the church. Around age 13, I decided that gay people were evil.” Then, a boy named Chance transferred into his school and joined choir. Iese was a senior, and new move-in Chance was a sophomore and had “the cutest face ever.” One day, Chance opened up to Iese about what had brought him from northern to southern California. When Chance had told his parents he was gay, his father became really angry and made sure it was “a really rough evening for Chance.” After crying himself to sleep, Chance woke up the next morning to find out his father had shot and killed himself. Later, his mom relocated them to Orange County for a fresh start. Hearing this, Iese opened his eyes to the dangers of homophobic rhetoric and behaviors—that Chance trying to connect with his parents over his orientation resulted in an undeserved outcome Chance would have to live with the rest of his life. “It didn’t seem right,” says Iese. “For the first time, I started questioning that maybe being LGBTQ+ was not evil.”

Years later, the power of story was what inspired Iese to take his peers’ distressing experiences to President Kauwe. It was never his desire to tell the university president (or the church) what to do, but to provide opportunities for increased understanding--an increase he himself had worked hard to gain—while letting the leadership know he trusted their revelatory processes. After high school, Iese worked a few jobs and went to community college before being called on a mission to Auckland, New Zealand, where he was excited to learn Samoan, the language of his ancestors. But instead of studying the language for hours a day as instructed, Iese recalls spending way too many hours searching the scriptures and church manuals to figure out why he was gay and how he could change it. Believing in President Boyd K. Packer’s admonition that “studying doctrine is more likely to change behavior than studying behavior will change behavior,” Iese convinced himself he could “study the gay away.” His obsession translated into a self-righteousness perfectionism in which he says he held others to unrealistic standards. It wasn’t until the end of his time in New Zealand that he met a fellow missionary who taught him by example how to finally find peace through Christlike love. A few years after his mission, Iese moved to Hilo, Hawaii, where he met a community of similarly loving members of the church who modeled pure love and gave him the tools he needed to become a more kind, caring human. This, coupled with an understanding bishop he’d had back in California who was a father of a gay son himself and helped Iese get into therapy, allowed Iese to undergo a process of “sandpapering away the levels of my pride and self-hatred. There were some rough, gritty sections, and some fine gritty sections, but either way, it was gritty and it took years.”

Iese recognized that heretofore, he’d been operating “like Javert from Les Mis,” with a rigidity that often created friction with others, including his two younger brothers. After his mission, when he came out to his family, he apologized for this behavior, and was met with a warm reception by his family, aside from an initial response by his dad at first trying to “fix him” by asking, “Have you really thought about this?” Iese laughed and replied, “Yeah, I’ve thought about this.” Iese was deeply touched by his mom’s response. An “impeccable human” who works as a concierge nurse and personal trainer, his mother tearfully opened up the day after he came out while the two were out for a walk about how much it pained her to think she never noticed how much her oldest child was hurting. She said, “You love the church so much and now life’s going to be so much harder for you and there’s nothing I can do about it… Was I so busy that I couldn’t see my boy was hurting and he couldn’t trust me to support him?” Iese says, “Here we were, walking the dogs and crying through the neighborhood… I never guessed my mom might feel that way. I thought it might be more of a ‘You’re ruining our eternal family,’ but no. My mom’s my hero. That was an A+ response.”

The call to bear and ease the burdens of others expanded beyond Hawaii for Iese. Besides instigating the fireside, while at BYUH, he had the opportunity to be a guest on both Richard Ostler’s “Listen, Learn and Love” podcast and Ben Schilaty’s and Charlie Bird’s “Questions from the Closet” podcast. After graduating, he pursued his master’s degree at ASU where he continued his advocacy efforts and has been asked to speak at institute and various ally events. Besides leading a high school choir program, Iese is now also the choir director for the Tongan ward he attends. He loves this ward, who overwhelmed him with support and flower leis at his recent masters’ program graduation. Last fall, Iese was asked to be the opening speaker at Gather, and he is eager to continue his efforts to magnify the voices and stories of LGBTQ+ members of the church from all over the world.

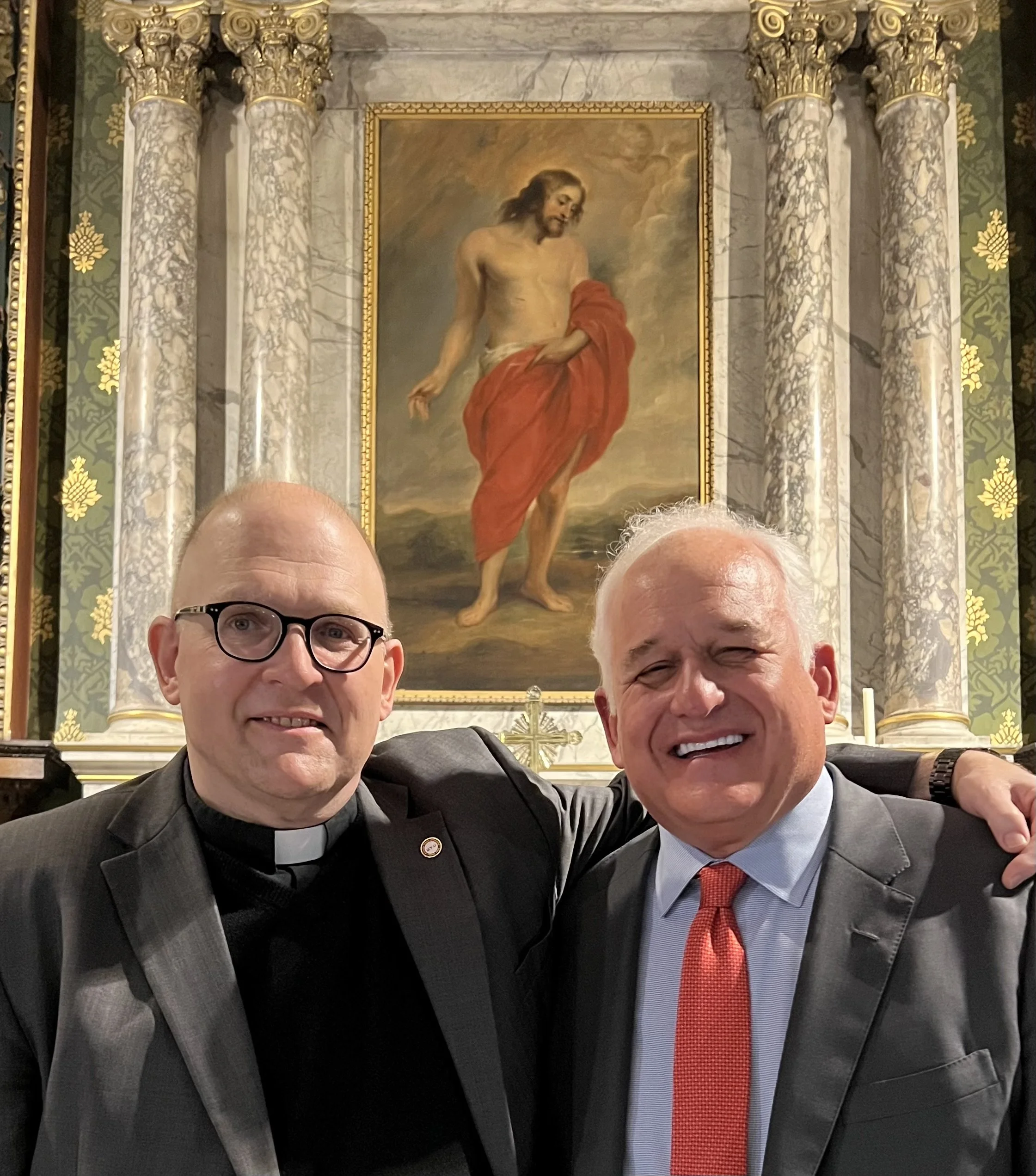

Iese has also recently experienced the joy of human connection, as he is now in a seven-month relationship with his boyfriend, whose family is involved in the performing arts. Iese says he appreciates how the Greeks have different words for love, which he has now come to better understand: “There’s agape for brotherly love. In the church, Jesus speaks of the communal family model of love. There is flirtatious love, but I wanted to understand romantic love, particularly as a conductor and trained musician. Having studied music through the centuries, one of the most studied topics is love, and I would be remiss if I didn’t experience it in this life.” Iese says he had to do a little work to gain the support of his boyfriend’s Christian dad, who at first resisted meeting him. But Iese laughs, saying, “I won him over by talking football and Jesus.” His boyfriend attended an ally event that Iese was speaking at. Iese watched with joy as his typically shy boyfriend was flocked by attendees after the refreshments and ended up sharing his story with strangers. Iese thought, “Look at him go; that’s my boyfriend.” On the way home, Iese’s boyfriend said, “I didn’t know what you meant by doing advocacy work with your church, but now I see and I understand. I want to support you in this, however I can. I want to stand by you in all this.” As for their future, Iese says, “Time will tell; but for now, I’m really grateful.”

ANONYMOUS

M* drives across state lines to seek the healthcare for her preteen daughter that has improved her sense of well-being. She tells very few people where she is going, as few seem to understand. But a nearby state allows a puberty blocker shot that’s recently been banned for minors under 18 in M’s home state. It’s a shot that has been widely given without major concerns for decades to patients with early onset puberty, until the politicking of the trans community dominated airwaves and stigmatized it as “unsafe.” It’s a shot that can help prevent the further need for medication for trans individuals if timed right, which is why the trans-affirming medical community prioritizes its use in younger patients on the verge of puberty. But this process requires a parent and a medical team to trust the intuition and identity of a patient who is still a child.

M* drives across state lines to seek the healthcare for her preteen daughter that has improved her sense of well-being. She tells very few people where she is going, as few seem to understand. But a nearby state allows a puberty blocker shot that’s recently been banned for minors under 18 in M’s home state. It’s a shot that has been widely given without major concerns for decades to patients with early onset puberty, until the politicking of the trans community dominated airwaves and stigmatized it as “unsafe.” It’s a shot that can help prevent the further need for medication for trans individuals if timed right, which is why the trans-affirming medical community prioritizes its use in younger patients on the verge of puberty. But this process requires a parent and a medical team to trust the intuition and identity of a patient who is still a child.

M does trust her daughter to know herself better than anyone, describing her as an intelligent and fun-loving home schooled young tween who has “read all the things,” says M. “I know she doesn’t know everything, but she knows a lot more than I do.”

Healthcare. Safety. Well-being. They are the basic human needs most parents desire for their children. But when a child comes out as transgender, the method of how best to pursue each ideal can vary drastically between parents, often creating unease at home. Societal pressures can isolate children and families who don’t fit the binary norms of a classroom or bathroom, further exacerbating isolation. State legislation can dictate what is allowed in the doctor’s office, resulting in mental duress. These are the common realities for families of trans kids, and when a child comes out at an especially young age, the collateral fears can drive the child or family right back into the closet.

As M views the best path forward for her daughter differently than her social circle, church community, and state legislature does, she is only out anonymously, as the creator of the Instagram account, @mama_trans_kid_in_the_closet. The community she has built on this account, as well as her Mama Dragons network, have served as a salve for M, who has appreciated having public forums to discuss social transitions, hormone replacement therapy, puberty blockers, and bathroom bills. They are topics she once knew nothing about, but her network and a helpful book, The Transgender Child: A Handbook for Parents and Professionals Supporting Transgender and Nonbinary Children by Stephanie Brill and Rachel Pepper, have contributed to her new vocabulary and understanding. They have also been able to get acquainted with adult trans women, who offer hope for what can be.

A self-described “Molly Mormon,” M’s advocacy for her children surprises even herself. But she’s grateful for the 2020 impression she had to study LGBTQ+ issues, coupled with Elder Ballard’s oft-quoted nudge for LDS members to learn more about the experiences of LGBTQ+ people. Feeling compelled to do a deep dive into something she had never thoughtfully considered, M picked up Charlie Bird’s book, Without the Mask, at Deseret Book, feeling it might be a “safe” source, then Ben Schilaty’s, A Walk in My Shoes, and began listening to their podcast, “Questions from the Closet.” More podcasts, including “Listen, Learn and Love,” helped her begin to consider what life is like for an LGBTQ+ member of the church.

After reading past church teachings and some messages about queer people delivered over pulpits that were “really tough to swallow,” M began to understand why people in this community were misunderstood. Still, when her daughter came out as trans, it was “super shocking” for M and her husband. “I had heard about trans kids knowing about their identity from a young age—always dressing up as princesses or pirates. But ours was typically into boy things. Even now, besides growing out her hair, she hasn’t expressed a strong interest in make-up or dressing in a feminine way often. Though she has yet to come out publicly.” She came out to her mom via a phone message exchange, sharing she had been feeling confused for some time, like she didn’t know what was going on. And then she said a prayer and had a moment of clarity as a thought entered her head: “I’m trans.” M says her child described suddenly feeling good about that, like God was telling her, “Yep, that’s it.” She felt excited to tell her mom then, having felt some peace about who she was. M says this was at first very hard for her to grasp. Like all their kids, this child was named after a beloved relative, so honoring the name and pronoun transition took some time for M. While navigating this new reality, shortly after, one of M’s older children came out as bisexual.

M feels grateful her kids have had each other’s support and are close, as they have lost friends over people saying disparaging things about LGBTQ. While she and her husband still attend, the church has been a tricky place for some members of the family. When one of her older kids was asked about their plans to serve a mission, their response was, “I don’t see how I can tell people to go join a church where people like my siblings won’t be treated the same as everyone else. It doesn’t feel right.” M’s bisexual child doesn’t feel like they fit in, but says they’d return overnight for the social structure, if the church changed their LGBTQ+ policies.

Bi-erasure is also a new vocabulary word for M. “One of the hardest things with the church is that the teachings on marriage and family are all clearly directed for someone to choose a male or female—the opposite gender—and do what’s expected of them… People assume you can just choose the more simple path, making it much harder for you if you don’t. Also, you’re in between two spaces, making you feel like you don’t fit or are forgotten.” M says when she goes to the temple she can’t help but notice all the binary division, and considers if her trans daughter could ever feel comfortable in church spaces. “Like if she did come to church, would they let her go to Young Women’s? I have so many questions. She doesn’t go, so it’s not an issue.” M’s trans child is only out to her immediate family members and a few others.

M says her kids don’t speak out against her church involvement, but she has explained to them, “I’m not going to church because I support everything they say, but because it’s what feels right, right now. I’d like to help create change. I don’t want to leave, but sometimes I feel so tired.” As someone who naturally wants to talk through her current struggles, M says, “It’s hard when you have a kid in the closet. You want to talk about it, but can’t when they’re not out.” So for now, she speaks out from a closet of her own. And she reminds people that this is a topic that affects everyone. “If you think you don’thave an LGBTQ person in the family, the chances are very slim you don’t. They have always been here; there is just now more vocabulary to be understood and people feeling safe to come out.”

M continues, “It can never be said enough: we parents of LGBTQ kids know our kids, and for those of us who’ve grown up in the church, this is me following inspiration and following my God who wants me to support my child. That’s probably the most hurtful thing I hear people say—that you’ve got to be careful to ‘not be deceived,’ like you don’t know the gospel, when it’s all you’ve known for your whole life.”

(M* = to protect her children’s safety and well-being, M has elected to remain anonymous)

SPENCER SMITH

This past week found Spencer Smith, 31, strolling through his favorite place on earth, churro in hand, as he worked his way from Big Thunder to Guardians of the Galaxy with a group of friends. “Disneyland is the only place I know of where a full-grown man can run up to a character and no one bats an eye.” For Spencer, it’s a welcome escape, and the “one place I can completely be myself, and no one even looks twice…

This past week found Spencer Smith, 31, strolling through his favorite place on earth, churro in hand, as he worked his way from Big Thunder to Guardians of the Galaxy with a group of friends. “Disneyland is the only place I know of where a full-grown man can run up to a character and no one bats an eye.” For Spencer, it’s a welcome escape, and the “one place I can completely be myself, and no one even looks twice.”

Most weeknights, Spencer’s location is the new Spanish Fork, UT hospital ER where he works as the attending pharmacist, ready to administer whatever life-saving medicine may prove necessary for car accident survivors or “people who decide breathing is an optional activity.” It’s a job he loves. In his spare free moments, he can often be found in his epic game room, where over 300 board games from Settlers of Catan to Carcassonne line the walls. The one place he never thought he'd be, however, was at last year’s Gather—a Christ-centered conference for hundreds of LDS, LGBTQ+ individuals and those who love them. For Spencer, attending Gather at first felt uncomfortable—like taking something he had accepted but wasn’t happy about and celebrating it. His orientation was something Spencer had never envisioned could or would be celebrated within the LDS context.