lift+love family stories by autumn mcalpin

Since 2021, Lift+Love has shared hundreds of real stories from Latter-day Saint LGBTQ individuals, their families, and allies. These stories—written by Autumn McAlpin—emerged from personal interviews with each participant and were published with their express permission.

AUBREY CHAVES

Aubrey Chaves has mastered the art of asking questions. As the co-host, alongside her husband Tim, of the popular Faith Matters podcast, Aubrey is known for her curious spirit and ability to ask complex, thoughtful questions of her guests, who range from scholars and theologians to therapists and philosophers. The conversations she helps lead are not surface-level; they probe deeply into the experience of faith expansion, and often, faith crisis…

Aubrey Chaves has mastered the art of asking questions. As the co-host, alongside her husband Tim, of the popular Faith Matters podcast, Aubrey is known for her curious spirit and ability to ask complex, thoughtful questions of her guests, who range from scholars and theologians to therapists and philosophers. The conversations she helps lead are not surface-level; they probe deeply into the experience of faith expansion, and often, faith crisis.

Her instinct for asking good questions stems from her own period of deep questioning. Around 2011, Aubrey’s husband read Rough Stone Rolling by prominent LDS scholar Richard Bushman, and it shook their world. Aubrey had picked up the book to better understand her husband’s wrestle as he sought answers as to how best to defend the church, but instead found herself devastated by its contents. She says, "It forced me to face questions I’d ignored so long because I thought if a question disturbed me, it must be from an outside source or not true."

What initially disturbed her most was church history, but over time she became even more troubled by the present-day implications—particularly the harm she saw in the church’s position on LGBTQ+ issues. History, she realized, was static, but current doctrine and policy were not. "I felt disturbed by some of what I read that I couldn’t explain—some things that were not doing active harm, but the position on LGBTQ was doing active harm."

Aubrey had long believed that the truthfulness of the church meant it was always aligned with God's will. But once that certainty began to crack, the weight of being complicit in harm became unbearable. She felt a sense of urgency to decide whether to leave or stay. She entered what she calls a "season of consumption"—a six-year period of reading, learning, and trying to resolve the dissonance. Eventually, she became more comfortable with uncertainty. She realized there might never be a single answer that could make everything feel tidy again.

With that realization, she began to redefine the church’s place in her life. Rather than seeing it as a source of all gifts and truth, she started to view her relationship to it as one where she could offer her own gifts and energy. Discovering the Faith Matters community and being asked to take over the podcast along with Tim emerged from this shift—a space to pour her energy into thoughtful conversation. She recalls, “It came about organically because we felt so desperate for connection, to find people asking similar questions and burdened by similar pain.”

Aubrey sees ongoing tension around LGBTQ+ issues as a large part of the necessary struggle. Though she wishes the church were doing more, she believes in the power of creating bridges through honest dialogue. One conversation that stayed with her was with LDS scholar Terryl Givens, who told her, "Sometimes we make an idol of our own integrity." That sentiment helped her understand why she continues to stay and engage, even when doing so is painful.

There have been many moments when it would have been easier to walk away. But she believes there’s value in remaining at the table, asking questions, building trust, and staying in difficult conversations. "I've stayed in the church to stay in the conversation—even if I'm in an excruciating conversation or at a table where we're not all aligned."

Aubrey has often felt conflicted about that choice. There were times when integrity seemed to demand something more finite—like leaving altogether. But she believes that defining integrity in such narrow terms might not capture the full picture. “Maybe we don’t always have to do all or nothing,” she reflected. “People feel a call and energy moving them to where they’ll be able to do the most good for their soul or community. For me, I felt it was okay to stay and be very uncomfortable—a calling to put my gifts and energy here.”

It took years, she said, to feel peace in that lack of alignment. But over time, she found that her discomfort became a source of transformation. “I use my gifts to push toward real change— trusting that transformation within my own circle of influence can create meaningful ripples.”

She describes the Faith Matters experience as one of healing and exchange. “It feels like healing flowing—we’re recipients as much as we put out,” she said. In the most honest conversations, even between people who completely disagree, she has seen something almost mystical happen. “There’s a magic moment where people are being vulnerable, honest, coming to the table in good faith, to connect. The technicalities of where you fall on one issue aren’t quite so loud because of this connection. The energy is so much softer.”

This shift, she said, feels worlds away from the “angsty arguments” that once left her feeling defensive. Instead, there’s a more grounded compassion, a willingness to understand.

In recent years, as Utah legislation has taken sharp turns that many have found painful, Aubrey has also felt the weight of needing to respond. “It never feels like enough to say our hearts are hurting, too, in Utah,” she said. “But whenever church things come up, I hope people feeling the most vulnerable and raw know that those of us who feel more safe are using our privilege. I hope it’s some comfort.” She sees her role as someone who can use her voice to open doors. “I’m hoping to be a resource—to get into a room for someone with a harder path. I hope they feel a sense of solidarity. I’m here, with linked arms.”

A large part of Aubrey and Tim’s allyship journey began while they were living in Boston. They developed a close friendship with a married gay couple—neighbors and classmates of Tim’s in business school. These friends, without ever explicitly trying to teach or convince, helped Aubrey and Tim see that their lives were fundamentally the same. Through genuine friendship, any lingering resistance Aubrey had simply dissolved.

"It was the universe’s gift to us," she said. "While asking big questions, we had this steady handful of friends. It was a totally unspoken way of breaking down any remaining barriers. They evaporated because we loved these people so much."

By the time they returned to Utah, Aubrey felt deeply committed to helping the church become more aligned with the inclusive spirit of Jesus. That experience solidified her sense of purpose. It also helped Aubrey and Tim learn how to be a safe space for others, especially for LGBTQ+ loved ones who later came out. They want to always be the kind of people who radiate unconditional acceptance.

In their Midway, Utah home, Aubrey and Tim are raising four children, ages 16 to 7. From the beginning, they’ve tried to make LGBTQ+ inclusion feel joyful. Each year, they go all out decorating for Pride month, turning it into a family celebration with rainbow-themed treats and signs.

Over time, their children have come to see LGBTQ+ identity as something to celebrate. Their youngest child doesn’t even recognize there might be tension around the topic. For her, learning someone is LGBTQ+ is simply fun and good news.

As their kids have grown, Aubrey has seen how these early efforts shaped them. They’ve formed meaningful friendships with LGBTQ+ peers, who often recognize their home as a safe space just by seeing a rainbow decoration or a photo from a Pride event.

One of the most powerful moments of visceral change in recent years came during last year’s Faith Matters Restore gathering, where Allison Dayton and John Gustav-Wrathall led a session together. Aubrey remembered watching the energy in the room shift as John shared his story. The audience, many unfamiliar with John or his journey in and out and back into the church while being married to his longtime partner, leaned in with openness and empathy.

John’s decades-long effort to seek fulfillment while holding on to what was important to him resonated deeply. Even attendees from more conservative backgrounds responded with compassion. Aubrey said it felt like "4,000 people leaning in together."

Faith Matters surveyed its audience, and LGBTQ+ inclusion ranked among their top concerns, alongside women’s issues. Most of their listeners are still active in their wards, navigating tension as they show up with love and faith. Aubrey hopes those who are struggling know they’re definitely not alone.

Reflecting on how to handle difficult conversations, Aubrey draws inspiration from Jonathan Haidt’s book, The Righteous Mind. She’s learned that trying to persuade through logic is rarely effective. Instead, she finds that storytelling and connecting at that heart level are always more productive for good.

By sharing what is honest and painful instead of confronting or creating tempting arguments, she has seen conversations shift and “connection across the table that does so much of the heavy listening.” It’s then that Aubrey knows, “Seeds are planted in those moments—and that is the most fertile ground for good fruit.”

Aubrey Chaves will be presenting at this year’s Gather Conference. To register, go to: www.gather-conference.com

DR LISA TENSMEYER HANSEN

Chapters. That’s how Lisa Tensmeyer Hansen describes the various seasons that have directed her to what she now regards as the pinnacle of her life’s work. All along, she has felt the guidance of an all-knowing hand…

Chapters. That’s how Lisa Tensmeyer Hansen describes the various seasons that have directed her to what she now regards as the pinnacle of her life’s work. All along, she has felt the guidance of an all-knowing hand.

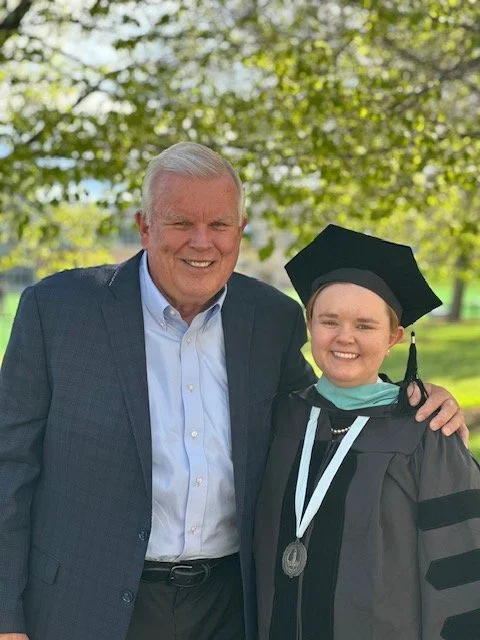

The PhD and LMFT now resides in the heart of Utah Valley with her husband Bill, where she is co-founder and CEO of Flourish Therapy, which provides life-saving therapy for LGBTQ+ individuals. While none of her seven biological children, her foster daughter, or other “bonus children” identify as LGBTQ+, they joke that “maybe someone will come out for mom for Christmas.” Besides having a gay nephew whom she adores--and who is soon graduating in vocal performance from the U where he started a gospel choir. Lisa agrees it’s interesting how her path has brought her to this particular space. But she can’t look back without recognizing she’s always had an awareness and empathy for those often deemed marginalized.

Growing up in the LDS church, Lisa says, “I spent a lot of time thinking about what God as parent would want their children to grow up and be and do.” As she experienced various stages of faith development, she started by believing in a God who had reasons for the rules, even those that seemed to make less sense. She began to recognize a God who valued development and not just blind obedience--a God who saw something in each of us that needs to be deeply valued and seen and understood.

As a teen, Lisa believed somewhat in the idea of “the elect”—that finding a way to be like God was a narrow path and not everyone was destined for eternal greatness. But as she became a parent, she recognized that every single individual’s growth matters. That everyone has been given something to bring them closer to God and something to believe in. This paradigm was further cemented when her youngest children’s involvement in a theater program enlisted her to serve as the program’s director. A former member of the BYU Women’s Chorus, Lisa also ran her stake youth choir and served in the stake Young Women’s presidency. In these capacities, she recognized how some of the most vibrant and lively performers were those brave enough to later come out as gay.

In their small community of Payson, it was easy for Lisa to see how the community of church and school did not provide a safe haven for these performers to be powerful leaders and contributors, despite their phenomenal skills and talents. She witnessed some be excommunicated because they identified a certain way. Another was refused participation in a temple opening extravaganza even after being selected for the top spot, because they were gay. She saw many who were relegated to second class citizen status if they chose celibacy, but “never fully celebrated as they would be if straight.” Lisa says, “That was a powerful message to me… These were not people who were anxious to leave God behind; these were amazingly spiritually deep people whose communities decided they had no place for them.”

In another chapter of Lisa’s development years, she witnessed racism firsthand. Growing up in Indiana, there were both schools and swimming pools segregated based on the color of one’s skin. When Lisa enrolled in an integrated college preparatory high school in her neighborhood, her understanding of what it means to live in a democracy with people who are treated as less than shifted as she heard various viewpoints and recognized her own privilege. At the time, largely due to the teachings she was immersed in via gospel discussions in her home and what was taught over the pulpit, she complacently believed that “God had reasons for the way things were,” even racism. Never hearing anything else, besides the incredulous objections of her more broad-minded classmates, Lisa assumed things would just be that way forever. As she matured in the gospel, and especially after reading Edward Kimball’s carefully crafted summary of the events leading up to his grandfather’s reversal of the priesthood ban in 1978, Lisa experienced a substantial eye-opening. She came to realize that it wasn’t the people waiting around for God to change His mind or make His ways known, but that the people themselves needed to change. She asked herself, “Are we content to keep others at arms’ length so we feel we are holy enough?” As this dissonance set in and Lisa pondered her participation in what she had always believed was the restored gospel, she had an awakening to the reality that even though Jewish leaders at the meridian of time when Christ was on the earth kept many from full participation, that God continued to work in that space. That this delineation didn’t obliterate Christ’s teachings about scripture, prayer, the law and prophets. Lisa says, “This seemed like a path I could emulate.” Perhaps there was something to be gained, or something to be done, in this space of nuance.

As she watched so many in the LGBTQ+ space be excommunicated from a church she as a straight woman could still belong to, Lisa decided to do what she could to elevate the LGBTQ+ community “in the eyes of people like me, and in their own right.” She decided to start a gay men’s chorus in Utah Valley, patterned after the one she’d seen in Salt Lake. “So many I knew cherished the Primary songs and wanted a sense of connection to God that was being denied to them,” she recalls, in reference to LDS markers like missions and temple marriages. It took awhile, but Lisa was able to put together a small gay men’s choir that rehearsed and performed at UVU, the state hospital, and various library holiday celebrations. Once Lisa went back to school, one member of the Utah County Men’s Choir started the One Voice choir in Salt Lake City, and most of the performers followed him to that organization.

With this goal achieved, after some prayer, Lisa felt what she should do next was go back to school with a focus on studying mental health. She knew this is where she could be of most use to the LGBTQ+ community within the context of LDS life, and ultimately chose her alma mater of BYU as the only place to which she’d apply, after a former colleague agreed to mentor her. “At 50 years old, I felt lucky someone wanted to work with me,” she says. The timing was ideal, as BYU was facing accreditation challenges in 2010 and needed to enhance their LGBTQ+ research—a role Lisa eagerly took on. As she put in her hours toward earning her LMFT and PhD, her first client in the BYU clinic was someone with gender identity questions. Soon after, Lisa received an influx of clients who identified as gay, lesbian, gender queer, nonbinary, SSA and bisexual. She says, “I felt like this was confirming a particular direction for my focus.”

Lisa was instrumental in starting a research group at the clinic based on Kendall Wilcox’s Circles of Empathy wherein gay people would come and share their experiences with straight student therapists. Through the four sessions in which it ran, therapists-in-training participated at least once to expand their understanding. She was also able to help a professor build his curriculum on the topic and has been asked back to the MFT program more than once to talk about LGBTQ+ clients. Of her time in BYU’s graduate program, Lisa says, “I felt a lot of support for the things I wanted to do to benefit and support the LGBTQ+ community while at BYU.”

Just as she was graduating with her PhD, Lisa was approached by Kendall and Roni Jo Draper about helping start the Encircle program in Provo, launching her into a new chapter. She recruited two clinicians she knew to help advise a program in which they could offer free therapy. Along with Encircle director Stephenie Larsen, Lisa was there for the opening of the first home in Provo, where Flourish Counseling Services was born (as a separate entity). While “it was the right thing at the right time,” as Lisa oversaw 13 therapists to meet the clients’ needs, ultimately Lisa parted ways with Encircle. However, she still refers young people to the program for their friendship circles, music and art classes, therapy, and as a place where “they can be themselves without their queerness being the most important thing about them.”

After moving off campus from Encircle with those 13 therapists, Flourish Therapy is now its own entity with 80 therapists offering approximately 2500 sessions a month in offices from Orem to Salt Lake, all on a sliding scale based on what clients can afford. Thanks to generous donors and insurance subsidies, Flourish is able to keep their session costs well below national average and even offers free therapy to those in crisis who cannot afford it otherwise. Lisa says, “We deeply depend on people paying it forward.” Because of the large number of therapists available, clients are often able to select a therapist with a similar gender identity or orientation, if they prefer.

Unlike LDS Social Services, Flourish is able to freely adhere to APA guidelines and honor their clients’ authentic selves, however they may show up. They have clients ranging from those trying to stay in the LDS church with temple recommends (whether in mixed orientation or same-sex marriages), to those trying to withdraw their names from the church or seek letters for transitional surgeries. Flourish also often treats missionaries referred by mission presidents when the assigned field psychologist perhaps might be struggling to understand. Lisa’s efforts have been widely recognized, and she considers it “a real honor” that the Human Rights Campaign gave her its Impact Award a few months ago. The Utah Marriage and Family Therapy Association also recently awarded Lisa Supervisor of the Year for her work in mentoring student and associate counselors and Affirmation International awarded her Ally of the Year for her work in steering Flourish through its first five years and maintaining its mission to support the LGBTQ+ community despite outside pressures to change their structure and process.

When the tough questions resurface and dissonance reappears, Lisa finds herself traveling back to the early answers she received in Chapter 1 living—when she first knelt and prayed around age 10 to ask whether Joseph Smith had really seen the Father and the Son. She says, “I felt an enormous feeling of light and love. I received no specific answer to my prayer, but felt a love wherein I recognized that something here is the answer and secret and why of everything. God feels this way about us here on earth–that’s what has sustained me all this time and made me feel that what’s inside of us is valuable to God. God’s not looking at us to shed what we have that’s divine but to lean into it and live and cherish and value the learning experience. We will then become able to recognize everyone’s lives—identity and all--as stepping stones.” Lisa concludes, “The things that are true about me are what have moved me into this space where I hope I’m lifting others to that same place wherein they can see how their Creator recognizes the value—the holiness—within all.”

AMBERLY BEAN

Every month, Amberly Bean, 30, leads the Lift and Love youth support group on Zoom. She opens each session of new attendees with the same introductory joke, “I identify as lesbian but I’m married to a man but we’re not going to get into that tonight, it’s a long story.” Amberly and her husband Kendall have known each other since childhood. In fact, he was the name she’d throw out every time her middle school friends talked about the boys they liked, feeling he was a “safe crush because nothing would ever happen.” She laughs that, “Even when Kendall would hear that, there were no moves made—which felt really safe for me.”

content warning - sexual assault

Every month, Amberly Bean, 30, leads the Lift and Love youth support group on Zoom. She opens each session of new attendees with the same introductory joke, “I identify as lesbian but I’m married to a man but we’re not going to get into that tonight, it’s a long story.” Amberly and her husband Kendall have known each other since childhood. In fact, he was the name she’d throw out every time her middle school friends talked about the boys they liked, feeling he was a “safe crush because nothing would ever happen.” She laughs that, “Even when Kendall would hear that, there were no moves made—which felt really safe for me.”

After serving her mission and attending college, Amberly now lives with Kendall once again in Idaho Falls, ID, where she was raised in a devout and loving Latter-day Saint family. The oldest of three children, from the outside, her upbringing looked textbook—kind and faithful parents, an active church life, a close-knit community. But Amberly always knew there was something about her that was different.

She had come out to a close group of friends in her teens. But nearing the end of her high school years, the inner tension she felt with her faith reached its peak. “It was all or nothing,” she believed, rationalizing she could either be a lesbian or a member of the Church. There was no in-between. While she continued to attend church with her family, she said mentally, “for all intents and purposes, I was out.” During her senior year, Amberly experienced a tough break-up with a girl that felt like it was destroying her. She finally felt it was time to come out to her family and all her friends who cared about her.

Grateful to no longer hide so much of herself with her mom, whom she had always felt close with, she remembers her reaction as being as supportive as she could be at the time. Her mom’s words made her intentions clear: “I’ll love you no matter what you do, you’ll always be a part of our family. Nothing will change. But I know the Book of Mormon and gospel is where you’ll find guidance.” Determined to prove her wrong, Amberly asked herself, “How can any part of this faith guide me when it doesn’t even believe I exist?” But two weeks later after finishing the whole book, Amberly’s heart was moved in a way she didn’t expect. “I felt God with me. I didn’t know what would happen with my dating life or my future, but I knew I could figure things out if I had the gospel.”

That conviction led Amberly to prepare for a mission, in the second wave of 19-year-old sister missionaries. She was honest with her local leaders about past relationships with women, which initially led to the direction to wait a year before serving. The delay devastated Amberly, who felt unsure whether a straight person would have been given the same edict. But a week later, she was asked to meet with her stake president again, assuming there had been a logistical error.

Instead, her stake president shared an experience he’d had in the celestial room of the temple, where he distinctly envisioned her kneeling in a small room (which she recognized as her personal oasis where she spent time journaling, playing guitar, etc.). He felt she was ready to serve, and needed to go right away. Her mission papers were submitted that night.

That was the first time Amberly says she felt a confirmation that there is a lot of misunderstanding with how the church deals with queer members and their “sins and transgressions” and “what Heavenly Father actually feels about His queer children.” She says, “It was a big milestone moment for me.” She felt a very strong impression from above that her queerness is a gift. She does not believe her Heavenly Parents sent their kids down and said, “You guys get to be queer because it’s a trial and hard, so good luck.” Instead she has felt, “this is too pure of a thing to be bad.”

Serving in 2014, Amberly felt a deep desire to tell her story, but at the time, there were few visible LGBTQ+ Church members speaking openly—let alone affirmatively—about their identity and faith. She was worried that her news getting out on the mission “might not be kosher” while she was away from home sleeping in bedrooms with girls. She shared her story with one of her companions who then took it upon herself to tell someone else which started whispers around the mission which, later in her mission, resulted in Amberly getting emergency transferred under the pretense that she was gay and had a crush on the companion. Amberly said, “That’s hilarious. The first part is true, but this has been the hardest companionship I’ve had. Even trying to like her as a friend was hard.”

By the time she returned home, Amberly was emotionally exhausted and unsure how to navigate church life again. Once again, she took a break. Dating girls at BYU–Idaho was difficult, but something she ended up doing. Then came another heartbreak. A woman she’d believed she would spend her life with ended things, saying she was bisexual and thought she could make a relationship with a man work—something she didn’t think Amberly could do.

Feeling conflicted and reminded of painful past feelings, Amberly committed to being the best celibate member she could be. She tried dating men, but after coming out to one—her only serious attempt—he sexually assaulted her under the false belief that it was his duty to “fix her.”

The experience was traumatic and left Amberly certain she would never date a man again. The aftermath was confusing as she initially sought the support of leadership but instead felt blame. But transferring her records to a YSA branch back home in Idaho Falls was a turning point. This branch president was operating off of a reliance on the spirit about Amberly’s past romantic relationships with women. Through this branch president, Amberly found healing and increased trust for leadership, and men in general.

Amberly slowly rebuilt her sense of safety and belonging in the Church. She got her temple recommend back and committed to being “the best celibate lesbian ever,” convinced it was the only faithful path for someone like her.

Then Kendall, her “safe crush” who she’d known since elementary school, re-entered the picture. Amberly ran into Kendall’s mom and joked again about any of the handful of her boys being marriage potential. Amberly retorted, “I’d marry any of your boys.” Her number was passed along, and Kendall reached out during a spring break visit home. When she suggested hanging out, he declined and said instead that he’d love to take her on a date. Their first date lasted hours—they couldn’t stop talking. “It was the first time I actually liked a boy for real,” she says. “And it freaked me out.”

She laughs as she reflects that, “As Mormon dating goes, after two weeks, he said, he didn’t want to date anyone else. You?” Two weeks in, Kendall asked Amberly to be his girlfriend. She knew she had to “ruin it and tell him,” and feared the impending break-up. “I’m a lesbian,” she said over the phone. “I’ve only dated women.” Kendall didn’t miss a beat. “Do you still like me?” he asked. Upon her affirmative reply, he said, “Then I don’t see a problem if you don’t.”

Kendall’s steady support has become a hallmark of their relationship. They started dating in March of 2017 and married that August, though they’d known each other forever. Kendall finished his studies in physics at the University of Utah, while Amberly moved to Utah with him to work.

Now, nearly eight years later, they are raising two children—a five-year-old son and a toddler daughter—and building a life grounded in honesty, humor, and mutual respect. “It hasn’t always been a walk in the park,” Amberly admits. “We’ve done counseling. But in the past few years, it HAS been a walk in the park.”

“Kendall is pretty chill and secure,” says Amberly. “He sees this as just a part of who I am. He doesn’t need a ton of outside support, though we’ve connected with other mixed-orientation couples. We talk enough to be each other’s support.”

The couple used to be involved with Northstar but now mostly affiliate with their Lift & Love community, where Amberly loves leading her monthly groups with Kelly Cook. “We usually have four or five kids show up, sometimes more. We chat, do icebreakers, let them go for it and they talk. I love it. It’s something I would have loved to have as a youth in the church.” She says, “Out of the queer kids who attend, they’re mostly still active in the Church, trying to navigate that. Their hope and optimism is contagious.”

Post-COVID and postpartum, four years ago, Amberly felt she wanted to be more authentic about her identity in their “very small, very Mormon community.” Coming out in her current ward was a process. For some time, she’d hidden behind her role as Kendall’s wife, struggling to feel like her authentic self. “I felt like a shell,” she says. “It festered.” She knew something had to shift.

“I told Kendall I needed to come out,” she says. “And he said, ‘Then let’s figure out the best way to do that for you.” With his support and the encouragement of a few trusted friends in her ward, including a YW president she served with who promised solidarity, Amberly began telling her story.

The result? “Not much changed,” she says. Her bishop came over to chat, and it was a good experience. She felt well supported. She says, “Even though I’m not talking all the time about how gay I am, it hardly comes up actually… But if it does in context, I feel the freedom to say something. I can be authentic.” She continues, “People in church don’t realize—coming out in church is not so I can talk about being gay, but so I can feel my friends know me. This is a big part of me.”

She wants her kids to grow up seeing the full range of possibilities, and will talk to them about it someday. “I want them to see that you can be queer and have a happy, fulfilled life in the Church. And I want them to see that people outside the Church can be happy too.” Amberly believes more people need to see both sides of the coin.

AMY GADBERRY

Amy Gadberry, 29, has spent much of her life navigating the complexities of her identity, faith, and mental health. Recently, the West Jordan, UT resident has come to fully embrace her identity as a cisgender bisexual woman, a realization that has profoundly shaped her ability to finally feel self-acceptance. Newlywed life has also brought a new form of happiness, as Amy and her wife Emily Tucker, just celebrated six months of marriage. But while her path has ultimately led her to a life she once only dreamed was possible, not much of Amy’s path to this point has been straightforward.

Amy Gadberry, 29, has spent much of her life navigating the complexities of her identity, faith, and mental health. Recently, the West Jordan, UT resident has come to fully embrace her identity as a cisgender bisexual woman, a realization that has profoundly shaped her ability to finally feel self-acceptance. Newlywed life has also brought a new form of happiness, as Amy and her wife Emily Tucker, just celebrated six months of marriage. But while her path has ultimately led her to a life she once only dreamed was possible, not much of Amy’s path to this point has been straightforward.

Though she recognized an attraction to men while growing up, Amy never had a strong desire to be with one. Even before meeting Emily, she envisioned a future married to a woman, a realization that initially caused her significant internal conflict. She grappled with whether to identify as lesbian or bisexual, feeling that the latter label carried a stigma within the LGBTQ+ community. At times, she questioned whether she was “queer enough” or had the same right to celebrate her relationship with pride. However, as she has come to embrace her marriage and the love she shares with Emily, these concerns have faded. She now feels that what matters most is the life they’re building together, and she could not be more grateful.

Having first become aware of her attraction to girls around the age of 12, Amy’s discovery came with a mix of shame and confusion. She noticed that the romantic feelings she experienced were different from those of her friends, which led her to suppress them for years. During middle and high school, she dated boys casually and occasionally even had boyfriends, but she says she never developed those deep romantic connections. College did not bring much more clarity, as Amy struggled to find a relationship that truly resonated. Eventually, she realized that her sexuality was something she needed to confront rather than continue to hide.

Raised in Maryland, Amy grew up in a deeply religious household where the church played a significant role in her life. Despite her concerns about how her faith community would respond to her coming out, she found unexpected kindness and support. At 22, after coming out to her therapist—who was the first person she ever confided in about her sexuality—Amy made the courageous decision to share her truth publicly through an Instagram post. To her surprise, she received an outpouring of love, even from those within her church.

Though they needed a little time to adjust once she started dating women, Amy’s parents have remained a steadfast source of love and encouragement since. Despite the initial acceptance she received, Amy ultimately found it difficult to reconcile her faith with her sexuality. In her early 20s, she attended church less frequently and eventually stopped going altogether at 23 or 24, except for supporting the occasional family event. Though she’s never harbored anger toward the church, Amy has experienced deep sadness over what she perceives as an impossible choice between her faith and the ability to pursue the kind of love she has since found.

A pivotal moment came when she attended a fireside where a well-known LGBTQ+ advocate within the church shared his story. His account of a beautiful life with his partner that ended when he decided to reconnect with the church struck a chord with Amy. She sat in the audience crying, and questioning why he had to choose between a life with his loving partner and a beautiful church community. She says, “It didn’t make sense to me, and ultimately was the straw that broke the camel’s back. I didn’t want to choose between the two but if I had to, I decided to choose love and companionship over the church. Since, it’s been a journey figuring out what I believe.”

Amy says she has managed to take the church teachings of her upbringing that resonated with her and keep them close to her heart. She maintains that she bears no angry feelings toward any church members, and that “a lot of people in my inner circle are still active members and good people who I know are uplifted by the church. It’s just not something I can continue forward with, and I’m ok with that.” She still maintains a strong belief in a God who loves and cares for all of us. And she genuinely believes, “God is so happy for me and all the children who are finding joy in this lifetime. That’s something the church taught me—that we are designed for joy.”

Joy has not always been easy to come by for Amy, though even her dark moments have cemented that there’s always been a higher power who cares about and speaks to her. Amy’s journey has been deeply intertwined with mental health struggles. Diagnosed with bipolar disorder and having struggled with an eating disorder, Amy has spent years navigating treatment, including multiple stays in residential centers. Her sexuality and faith crisis contributed to her struggles with suicidal ideation, leading to some of the darkest moments of her life. However, through therapy, support from loved ones, and inner resilience, Amy has persevered and found her way forward.

In February 2022, Amy entered her final residential treatment program, where she worked extensively on self-acceptance and coping strategies. She emerged from treatment in May of that year with a renewed sense of self-worth. That summer, she moved out of her BYU housing in Provo, eager for a fresh start. It was then that she met Emily. Their love story began on a dating app, where Amy was immediately struck by Emily, saying “She was one of the prettiest girls I’d ever seen.” After matching, they quickly hit it off, leading to a dinner date the next evening.

Their conversation flowed effortlessly, and Amy knew she had met someone special. Emily had never dated a woman before, and she was in the process of reconciling her lesbian identity and deciding whether she belonged in the church. Their connection deepened as they navigated their days together, making it official within just a few weeks. They dated for two years before marrying in October 2024.

Reflecting on their relationship, Amy describes it as the best two and a half years of her life. She says, “I never imagined a life for myself where I’d feel as happy and fulfilled and as good as I do now. I credit a lot of it to therapy and treatment, and also to the fact that Emily and I are a good match, which is a testament to the validity of what LGBTQ+ love and relationships can be. I felt I couldn’t ask for anything better, or imagine myself with anyone else. When you know, you know.” Amy describes the sentiment of their first weeks together, saying, “I knew she was my person and would be forever. She felt the same. It’s a reminder this love is not wrong, no matter what people say and what views they have. We know it’s the right thing for us. The life we’re creating together is the best life either of us could have ever asked for. It’s pure joy, and I’m so grateful every day for it.

Both Amy and Emily are fortunate to have families that fully embrace their relationship. Amy says her in-laws are among the most loving and accepting people she has ever met, treating her with the same warmth as they show any other family member. Though her own father initially struggled, he ultimately supported her wholeheartedly, walking her down the aisle at her her wedding, and fully embracing Emily as part of the family.

Amy attributes much of her inner strength to her mother, Tricia Gadberry. From the moment Amy first came out to her mother, while sobbing over the phone, Tricia has remained a pillar of support. Amy appreciates how she listens without judgment and provides a safe space for Amy to process her emotions. To this day, Amy considers her mother to be one of the most important people in her life, and a source of love and guidance she will always cherish.

Currently pursuing a graduate degree in school counseling, Amy plans to graduate in August and is actively searching for a job. She appreciates how her mother-in-law is helping the process by leveraging her connections in the education system. Emily also works with kids as a behavior analyst. Amy’s ultimate goal as a counselor is to be a safe and supportive figure for LGBTQ+ students, particularly those who may feel isolated or unaccepted. She is especially passionate about advocating for transgender students, and ensuring they receive respect and validation despite discriminatory policies that may exist within school systems. She says, “My heart goes out to all trans students now navigating this legislation and the hatred they’re experiencing… I want them to feel like they can talk to me about anything that goes on and that their existence is valid.”

Beyond their activism and careers, Amy and Emily lead a fulfilling life filled with travel, outdoor adventures, and quality time with their beloved pets, Bella (a dog) and Leo (a cat). While they love their roles as aunts to nieces and a nephew, they feel their fur babies may be the only babies they raise. At home, they love to watch reality TV and when the weather cooperates outside, Amy enjoys teaching Emily tennis. In turn, Emily has been teaching Amy canyoneering and water sports.

This October, the couple plans to celebrate their one-year anniversary with a trip to the Netherlands, the first country to legalize same-sex marriage. They are currently feeling out the possibility of living abroad in the future. In the meantime, during what has felt like dark days for many in Utah, Amy is buoyed in knowing that so many allies are out alongside them there fighting and wanting the best for their LGBTQ+ loved ones and others. Amy says, “The only way I can get through it is to find the parts of hope that come with it. Seeing others fight gives me hope. There will always be people who care, even if you don’t know them personally.”

MADDIE FOX

Every February is Bald Eagle Month in Utah, and Maddie Fox (she/her), takes full advantage of the season. A self-described amateur wildlife photographer, Maddie, 35, sets out early on one February Saturday a year to photograph her favorite creature. While she’s also garnered a frame-worthy collection of bison, elk, wild horses, and black bears, there’s something about the way the bald eagles soar overhead as they migrate south looking for food—so free and unencumbered—that captivates her…

Every February is Bald Eagle Month in Utah, and Maddie Fox (she/her), takes full advantage of the season. A self-described amateur wildlife photographer, Maddie, 35, sets out early on one February Saturday a year to photograph her favorite creature. While she’s also garnered a frame-worthy collection of bison, elk, wild horses, and black bears, there’s something about the way the bald eagles soar overhead as they migrate south looking for food—so free and unencumbered—that captivates her.

The proximity of her West Jordan home to the mountains affords Maddie opportunities to enjoy other outdoor activities like hiking and rock hounding for minerals and gems in the state in which she was born and raised. But as of late, she has been less than enthralled with recent Utah legislation that affects the trans community she is a part of. She says, “Transgender people just want to go about living our lives. We are who we are, the same people we always were—we’re just trying to match our external to who our internal selves tell us we are.” In a state that has now passed some hostile policies including the recent bathroom bills and legislation preventing PRIDE flags from schools and public buildings, Maddie continues, “I wish people knew that I am not the threat politicians say I am. I’m kind, loving, and just want to have the best quality of life I can being my true authentic self.”

For Maddie, her authentic self has felt “different” for as long as she can remember. Growing up, she didn’t know what it all necessarily meant, but she always felt something was unique about her. While she was assigned male at birth and grew up playing sports like basketball and baseball alongside her two younger brothers, Maddie typically felt more drawn to feminine things until a sense of shame would inevitably set in. Maddie grew up in the church, and later loved serving a mission to Ireland, but saw when she returned home after two years, her feminine feelings had not gone away as she’d presumed they would. This time, she got into a therapist who helped her work through various thoughts. After some time spent building up trust, based on all Maddie shared, she was diagnosed with gender dysphoria.

While Maddie had experimented with wearing women’s clothing intermittently throughout her life, she started officially socially transitioning about a decade ago, at age 25. Six months ago, she began hormone replacement therapy, which she says has greatly helped with her gender dysphoria and increased her ability to feel authentic and “much more happy.”

With the recent shift in transgender policies instituted by the LDS faith, “and even before then,” Maddie says she has experienced a faith awakening. Last August’s policy shift has made activities and second hour meetings too difficult for her to attend. Now, she says, “With the policies, I just kind of go for a sense of community, but I don’t know where my faith journey will lead. I am still blessed to have a knowledge of my Heavenly Parents and their love for me.” Maddie says her family is coming to terms with her transition and she is grateful to feel their unconditional love.

Besides working at a university as a testing proctor and enjoying outdoor activities, Maddie stays busy watching college sports – with football being a favorite. She also belongs to a few support groups for trans individuals that she attends as her work schedule allows. Maddie takes comfort in hearing others’ similar stories and seeing how they live her lives. “I see what I can take from them and apply it to my own.” Maddie also identifies as lesbian ad has dated a little. She says, “Being trans and lesbian can be difficult here in Utah. I hope one day I can find someone I can date and settle down with and have a relationship.”

As the temperature rises nationwide when it comes to LGBTQ+ issues, Maddie says, “I wish that whether it’s church or state or federal that they would get input from transgender individuals who have lived experience instead of listening to the fearmongers.” Maddie prefers a gentler way, much like the nature of Jesus as portrayed in her favorite TV show, “The Chosen.” She says, “How Jesus is portrayed in The Chosen is how I see my Savior. That’s how I imagine He would be.”

JOSH HADDEN

Josh grew up feeling a bit different. He loved playing with girls' toys and even asked for a My Little Pony Dream Castle when he was four-years-old. His favorite colors were pink and purple, and he tended to get along better with girls than the other boys his age. This went on until around seven-years-old when Josh started to learn what the word “gay” meant, and then subsequently started to try and hide those parts of himself. He spent years trying to convince himself that he was not gay and that if he tried hard enough, he could hide this part of himself from everyone. In fact, Josh decided being gay would be something he would need to spend his life hiding, managing and changing. The frustration of that journey has only been alleviated in the past few years as finally, at age 26, Josh has come to trust that he was intentionally created as he is by loving Heavenly Parents.

content warning - suicide ideation and the death of a parent are mentioned

Josh grew up feeling a bit different. He loved playing with girls' toys and even asked for a My Little Pony Dream Castle when he was four-years-old. His favorite colors were pink and purple, and he tended to get along better with girls than the other boys his age. This went on until around seven-years-old when Josh started to learn what the word “gay” meant, and then subsequently started to try and hide those parts of himself. He spent years trying to convince himself that he was not gay and that if he tried hard enough, he could hide this part of himself from everyone. In fact, Josh decided being gay would be something he would need to spend his life hiding, managing and changing. The frustration of that journey has only been alleviated in the past few years as finally, at age 26, Josh has come to trust that he was intentionally created as he is by loving Heavenly Parents.

Throughout high school, Josh tried to ignore his feelings and pray for his orientation to change. In college at BYU-Idaho where he studied communications, he knew he was gay but continued in his efforts to find that one special woman who would magically capture his eye and his heart--the woman with whom he could make everything work. He recalls, “Over years of dating, I managed to get a fair amount of girls to like me, but after never being able to like them back, I just felt like I was toying with people’s emotions and hurting people.” Josh decided it was time for dating to take a backseat.

The following years, Josh experienced extreme loneliness. It’s an uncomfortable thing for him to acknowledge now, but he remembers praying he could just disappear. “Some might call it being passively suicidal, but for me, I just didn’t want to exist. I didn’t have a lot of hope for my future as I had no intention to date or marry a man and forfeit the covenant path for myself. But dating women felt so uncomfortable and I just felt so alone,” Josh reflects.

He continued in this tumultuous pattern of managing his conflicting desires to not be alone and to stay active in his faith while ignoring his strong desires to be with a man. “It was a life in conflict,” Josh says. In 2021, he realized he was in really bad shape when his father passed away from Covid. Josh had learned in marriage and family classes about the emotional process of grief and that studies had shown that the most intense pain people typically experience in life is the death of a child, parent or spouse, followed by divorce. Josh says, “I realized at that time that I was experiencing more emotional pain everyday as a gay member of the Church than what I felt in the peak of my grief over my dad’s passing. There’s a note in my phone where I journaled my thoughts on how everyone was being so kind and supportive, yet I was wrestling something so much bigger and more long term--something I had so many more questions about. And I was fighting that silent battle with no support.” Josh recounts how he’d been raised to understand that doctrinally, he knew how he could fit into the kingdom as a son who’d lost his father, but he had huge questions about whether his Heavenly Father could love him and have a place for him as a gay man. At this point, Josh realized something was seriously wrong and it was time for him to start opening up to others.

At the time, he had only told a few close friends on a case-by-case basis about his attractions. He never discussed it with his dad before his passing, but had one conversation in high school with his mom about it. He recalls there was a “silent acknowledgement, but it died there and was not discussed again.” However, after Josh’s dad passed away, he says his family “got more real” about things and he was able to revisit the conversation with his mom, who he says has since proved to be “a rockstar.”

Over the years, being gay became the subject for many of Josh’s prayers. For years, he prayed that it would be taken away and that he could be happily straight and fit into God’s kingdom the way he had been taught. After some time and realizing that his orientation would not change, he changed his prayer to ask God to just find one woman that he could be attracted to and be happy with. Then again, after many seasons of prayers unanswered, Josh decided that maybe he was praying for the wrong thing and changed direction. He started praying that if he would never successfully date or marry, that he could just have a best-friend. Someone to rely on and be close with in life. This prayer also proved unsuccessful, so he made another pivot. Josh changed his prayer to accept that he may be alone in this life, and his prayer was that in his life of solitude, that God would help him feel peace, contentment, and happiness where he was. Yet, Josh still felt painfully lonely.

After finishing school in Idaho, Josh did what many LDS singles do and moved to Utah. There, he hit a low point, and his years of unanswered prayers seemed to pile up. He experienced more intense loneliness after his move to Utah and nothing seemed to change. For a long time, Josh had dealt with his loneliness in dating by keeping close friendships, but during this new chapter of his life in Utah, that support wasn’t coming. He did everything he could think to do in making new friends and made it a serious matter of prayer, yet nothing seemed to change. After months of that intensified loneliness, Josh came to remember that old saying that the definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over again, but expecting different results. It was at this time that Josh identified that the one thing he had not yet tried was dating a guy.

Deciding to dip his toes in, just to see how it felt, Josh offered up a prayer, “Stop me, God, if this is wrong.” But Josh quickly found a guy he liked, went out a few times, had a good time, and felt utter confusion because nothing about dating this guy felt wrong to his spirit. His excitement over these new possibilities weighed against a lingering sense of despair for his future. After one of his dates, Josh prayed, “God, how did I get here? You know that for so long I prayed for Plan A, B, C… to happen and now I’m on Plan F.” But now, Josh also felt ready to listen. After pouring out his heart in prayer,the answer he received was, “Josh, I know. I know your heart and your mind. And I have been there every step of the way, yet this is where I have allowed you to be. And this is ok.” Josh says his mind at the time added a “for now” to the end of that prayer, rationalizing that all this was still to prepare him for marrying a woman. That was a year ago, in March of 2024, and the messages Josh has received since have been consistently the same. Every time he starts to feel unsure about his future, he feels God reassuring him, “You’re so afraid about leaving me, but I’m not worried about that. I have other children who don’t want to be with me,and I know how that feels. But Josh, you are not one of them. This will be ok in ways you may not yet understand.”

With that assurance, Josh proceeded in dating guys. He ended up moving from Orem to Lehi last summer, where he said his social life really changed for the better. He moved closer to some old friends he’d met while serving as an FSY counselor, and has been able to make many more friends since. Surrounded by friends, he’s been able to stay active in his ward where he serves as executive secretary alongside a friendly bishop who’s aware of his situation. After a few months of improved peace both in friendships, and in this new chapter of dating men, Josh decided it was time to prioritize coming out to his family. The youngest of seven kids, Josh remains close to his siblings and mom, most of whom live in Arizona. When he finally felt it was time to come out to his siblings, he realized that might be tough to do in person at a big family event, so he opted to share his news via text:

I’m sorry if this text message is a little uncomfortable or badly timed but I wanted to take a step towards living more honestly and let you know that I’m gay. I’ve kind of always known and I’ve been talking to Mom about it for years and just figured I should probably let my family know.

In no way am I planning on changing my relationship with God or the church but I just wanted to let you know. I’m the same old Josh I’ve always been.

I would totally love to talk about this with you some time either on the phone or in person! I would’ve told you sooner if we lived closer or had more time to talk privately. I’m always happy to talk about it and answer any questions you might have.

And this doesn’t need to be a secret either, feel free to talk about it openly with anyone you’d like. I’m telling the other siblings, too.

Anyways, I love you, and I hope you can still love me.

Josh received all positive responses, with his brothers acknowledging that his road must have been tough, while assuring him they were proud of him. He laughs that his sisters are supportive as well and like to keep in touch and ask for dating updates.

Recently, as another step towards peace for himself, Josh decided to come out publicly in a post on social media. He says the responses were overwhelmingly positive and that he feels much more at peace in his life now, having nothing to hide.

That increased peace has led him to try online dating and join Hinge. He’s enjoyed Hinge with its increased specifics on profiles as he’s remained selective in trying to find a man who is friendly toward the church (which is admittedly hard to do). Josh recognizes he’s experienced a lot less antagonism than some do, as his family, friends, and leaders have allowed him to be true to himself. He can see how things might be different if this hadn’t been his experience.

Josh recently returned from a night out and was telling his mom how his date was newer in his coming out journey and that his family had not responded well. Josh asked his mom what contributed to her having been so kind and supportive. She responded that it just took time. By the time he was ready to fully come out, she’d spent lots of time reading the stories of people who knew they were gay and their journeys. She felt she saw patterns of people who tried to pray it away, then tried to plead and bargain with God, and then tried to date members of the opposite sex with hopes of getting married in the temple. She’d read how these people tried every avenue but were met with defeat after defeat. And eventually, she’d seen how they typically did best when they came to the point where there was nothing left to do but be themselves. She observed that sometimes, your entire life as a gay person is a secret until you’re out, with those around you never seeing your silent struggles for years. Because of these witnesses,

and the very lived experience of her son, Josh, she says, “I feel more at peace just accepting people where they are.”

As for Josh, he currently loves his hybrid remote job and coworkers, working for an elementary education company in Orem. An avid outdoorsman, he enjoys adventurous hobbies like hiking, swimming, running, cliff jumping, backpacking and camping. For Josh, a perfect date might include a short nature walk around the pond and getting ice cream. He is looking forward to a summer full of adventures and hopefully some fun dates in the future.

MONICA, HORACIO, & CAYLIN

Monica Bousfield met her husband Horacio Frey in the fortuitous aisles of Babies R Us, where they both worked in the early 2000s. At first, they were just friends. Then best friends. Then after about a year of hanging out constantly, they surmised they must be dating. A year later, Monica nudged Horacio that it was probably time for them to go ahead and get married. After an eight-month engagement, they did, and while they eventually both left Babies R Us, their commitment to each other later resulted in two babies they would together raise. Through all this, Monica kept her maiden name—primarily because she’d never known of another couple like her and Horacio to last, and she didn’t want to complicate legal paperwork around having to undergo name changes twice. Monica had never heard of a woman marrying a gay man and having it not end in divorce. While she’d known Horacio was gay from their early days of hanging out, there were two other things she knew about Horacio: he was her best friend, and she wanted to marry him. Over two decades later, the couple is still making it work in Westminster, Colorado, where they have two children—Caylin, who is 17 and also identifies as queer, and Dominic—13.

Monica Bousfield met her husband Horacio Frey in the fortuitous aisles of Babies R Us, where they both worked in the early 2000s. At first, they were just friends. Then best friends. Then after about a year of hanging out constantly, they surmised they must be dating. A year later, Monica nudged Horacio that it was probably time for them to go ahead and get married. After an eight-month engagement, they did, and while they eventually both left Babies R Us, their commitment to each other later resulted in two babies they would together raise. Through all this, Monica kept her maiden name—primarily because she’d never known of another couple like her and Horacio to last, and she didn’t want to complicate legal paperwork around having to undergo name changes twice. Monica had never heard of a woman marrying a gay man and having it not end in divorce. While she’d known Horacio was gay from their early days of hanging out, there were two other things she knew about Horacio: he was her best friend, and she wanted to marry him. Over two decades later, the couple is still making it work in Westminster, Colorado, where they have two children—Caylin, who is 17 and also identifies as queer, and Dominic—13.

While Horacio has known he’s gay since a young age, this is the first time he has come out publicly. His childhood was marked with hardships, having suffered abuse and being adopted at age eight, which created abandonment issues. He came out to a few friends and his parents in high school, but very few people knew he was gay when he married Monica. He had been raised in a Christian church community in Santa Fe, New Mexico. While it was an open affirming congregation, Horacio opted for the white picket fence and kids route that was so highly encouraged. When he met Monica, she was not active in the LDS faith of her family of origin, but after their daughter was born, Monica says, “I realized I had this amazing, super special kid, and started going back to church gradually and then more actively.” After about five or six years of attending by herself with Caylin, Horacio converted. Monica laughs that she has the kind of mom who, every time they went to her house for dinner, would make sure the missionaries just happened to be there. Finally, Monica says, “She had a set there with the right personality at the right time.”

Horacio’s bachelor’s degree in Information Systems Security brought him to Colorado. After receiving her bachelor’s at what is now UVU, Monica started a graduate school program in counseling at CU Denver. But three years into the program and then married, she found while she loved learning about counseling, she had no desire to go into the practice. Instead, Monica went into management at Babies R Us, and then got her masters in HR. Now she works for a local municipality in compensation and benefits, a job she loves. Horacio works as a tech manager for a solar company.

Monica says, “if you’re going to marry someone who’s gay and you’re not, you need to be pretty confident, but we figured we’d never know if our marriage would work out unless we got married.” The beginning of their union felt lonely for Monica, having no one she could talk to who could relate to her variety of issues. “I internalized a lot, which is probably not healthy. But I didn’t want to out him. When others would talk about how great their marriage was, I was like, ‘Um, yeah…’” Monica didn’t actualize that hers was not the only mixed orientation marriage in existence until a few years ago. But of her almost-exclusive status, she says, “It doesn’t go away and it’s not easy. I’m not going to say it’s not worth it, but it’s not easy.” Horacio agrees it’s been difficult as well from his perspective with the couple talking about it, then not talking about it, when perhaps they should have more often. But after lots of counseling, he says, “We’re committed to making it work and have no interested in getting divorced or not making it work.” Monica appreciates how Horacio is still her best friend, despite the complexity of their issues.

Five years ago, new information about their children brought the two even closer together. Around the same time that Dominic (at age 8) was identified as being on the autism spectrum, Caylin revealed that she’s queer. Of their kids, Monica says, “She’s very creative, and he’s very, very logical. It’s two extremes, and definitely makes things interesting.”

While Monica was shocked about Caylin’s admission, Horacio was not as surprised, after Caylin had recently played Christina Aguilera’s “You are Beautiful” at the dining room table and asked her dad if he’d still love her if she came out. It was 2020 during the pandemic, and the family had spent much of their time together in quarantine. One afternoon, while on her way to her first outing to a friend’s house in a long while, Caylin sat in the back of her parent’s car, quietly drafting a text. She didn’t hit send until she’d safely entered her friend’s front door, and Monica and Horacio drove home in shock, processing. Besides the blindsiding of the information itself, they were now also apparently “old” because they had no idea what Caylin meant by: “I’m coming out as pansexual.” Monica googled it on their drive, while her heart stung with the second half of Caylin’s text: “I hope you still love me after this is over and done with.” Of course they did, she says.

However, needing more time to process as she hadn’t heard of a 12-year-old coming out that young before, Monica sent Horacio to pick up their daughter. When he pulled up to the house in a slight rainfall, he saw a rainbow in the sky behind Caylin’s friend’s roof. A scene that felt “picture perfect.” Caylin got in the car and Horacio abruptly revealed he was mad at his daughter--only because she had told him in a text and not in person. The two went and got ice cream at Chic-fil-A (Monica now laughs at the irony of that), and Horacio explained to his daughter that he was in a position to understand what Caylin was feeling. He revealed, “Not that I want to steal your story, but I understand because I identify as gay.” Horacio went on to explain how Caylin could still have church values, even though there is a lot of stigma in church communities about how to act. Horacio clarified, “You don’t have to do anything you don’t want to. Your mother and I still love you and will navigate with you, and you’ll get through it.”

Caylin says she’d known she “was some flavor of gay” since age nine, just growing up in the internet age, though she didn’t always have words for what she felt. She now prefers to identify as queer instead of pansexual, and says it has been hard to “figure out what I actually am and to surround myself with people who would accept me, especially in the church where a lot of people don’t necessarily agree with all of that.” Now a senior in high school, the church is still a part of Caylin’s life as she attends sacrament meetings on Sundays, but she prefers to go to Relief Society with her mom over Young Women’s. She also prefers to avoid seminary and youth activities, and keeps quiet about how she identifies at church. The family’s ward is small and skews a bit older and more conservative. With few youth, there are fewer opportunities for friendships. Caylin says her school has its ups and downs, but she has a good friend group and likes to do art and read fiction and romance books--the Caraval book series being a favorite. She also participates in theater, and is on the costume crew for the school’s current production of Chicago. While dating has been a part of her teen years, she’s not currently seeing anyone.

Shortly after Caylin came out to her parents at age 13, she was sitting at a stoplight with her mom. Monica remembers her saying, “Mom, I don’t know why God hates gay people.” Monica asked what she meant by that, reiterating that God loves everybody. Caylin replied, “I don’t know why gay people can’t get married in the temple, have kids, and do all the things.” Monica feels this messaging kids receive while sitting in the pews is important to share, as the words hit hard and create more harm than some may intend. While it took Monica herself time to process the news Caylin shared via text that day, she now feels protective “like a mama bear” and wears a rainbow pin and speaks up when it feels appropriate, which can be hard to gage in their ward. Horacio also wears some sort of rainbow every Sunday.

The family has attended some of the events sponsored by their local ally group Rainbow COnnection, which was started by members of their stake. While Monica’s an introvert, she values the gatherings. In her extended family circle, people tend to more quietly share big news to avoid big reactions. Monica has appreciated how talking with her relatives about Caylin has strengthened her relationship with her family members who were raised in a world where their family “looked good on the outside but weren’t that close.” Nowadays, they’re working on being closer at home.

Caylin says sharing a unique identifier alongside her dad has helped her to feel less alone. She now focuses on not letting others’ opinions bother her. One Sunday, after a lesson in which someone expressed how they had a kid “struggling with LGBTQ issues,” Caylin walked out into the hall and toward their car, confidently telling her mom, “I’m not struggling with LGBTQ issues. I’m quite good with them.”

For Monica, who has kept much close to her heart over the 20+ years of her marriage, she longs for a day when it feels more comfortable for people to share what they’re experiencing at church in a real way, instead of trying to present the image of “being perfect.” She says, “Wouldn’t it be wonderful if people could say, ‘I’m really struggling with this,’ instead of ‘Life is great’! I’ve dealt with a lot on my own, which is probably not the best way to handle things.” She continues, “It’s good more people have been talking about this in the last few years. It’s important to get out there and hear about it and share, so you don’t feel so alone.”

MARY ANN ANDERSEN

Mary Ann Andersen had always believed that love was unconditional, yet nothing could have prepared her for the totally unexpected revelation that would reshape her life and her marriage. For years she had built a life with Dave, a man she knew as a devoted husband, caring father of four, and committed member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints. Their days were marked by shared routines: family dinners filled with laughter, lively discussions, the typical demands of raising kids, and the steady pressure of church and community service. Yet, beneath this familiar rhythm lay a secret that would eventually alter the contour of their relationship…

Mary Ann Andersen had always believed that love was unconditional, yet nothing could have prepared her for the totally unexpected revelation that would reshape her life and her marriage. For years she had built a life with Dave, a man she knew as a devoted husband, caring father of four, and committed member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints. Their days were marked by shared routines: family dinners filled with laughter, lively discussions, the typical demands of raising kids, and the steady pressure of church and community service. Yet, beneath this familiar rhythm lay a secret that would eventually alter the contour of their relationship.

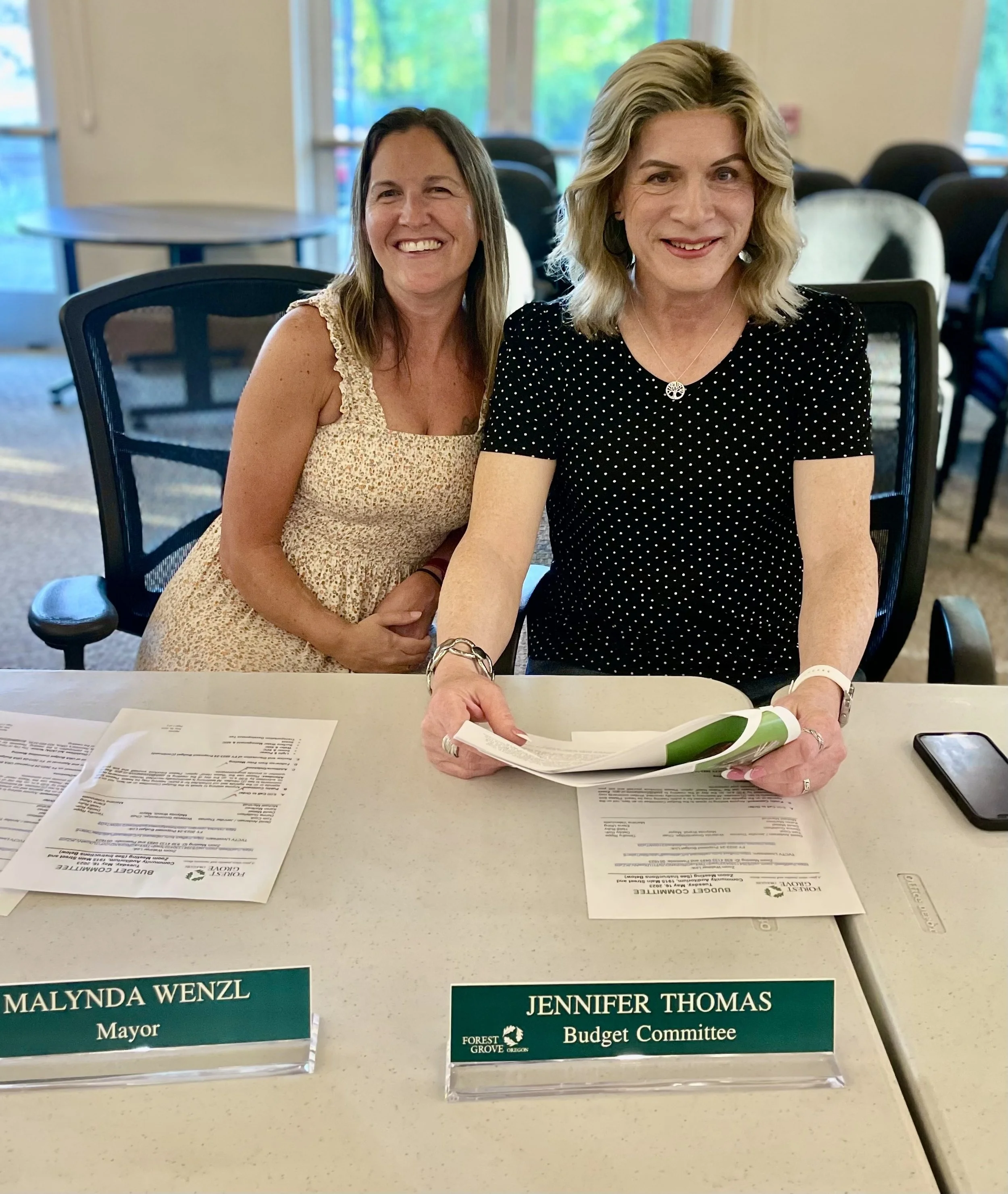

It began 14 years into their marriage in 1993, when Dave confided in Mary Ann about the inner conflict he had carried since youth—a dissonance born of a desire to express a feminine side he had long kept hidden. At the time, Mary Ann was busy raising four kids and managing a farm and bed and breakfast while Dave worked full-time and served as the bishop of their ward. Dave had always gone to great lengths to keep his feminine interests and clothing hidden, though Mary Ann had observed how complementary Dave was about how she did her own hair and makeup. “It didn’t make a lot of sense back then, but I just thought what a goldmine of a husband I had that he even noticed. But really Jennifer was living her life through me.” While some wives might have loved having their husbands encourage more facials and makeovers, Mary Ann started to resent this, wondering if she wasn’t attractive enough for her husband.

Back then the term “transgender” was nearly unknown, and the idea that the man she loved might also be the woman he felt inside was as bewildering as it was painful for Mary Ann. She remembers that Dave’s first hesitant admission was filled with both fear and hope for understanding. As Dave revealed that he carried within him a longing to be seen as female, Mary Ann felt shock, confusion, and an aching vulnerability. She wondered if her husband was gay and wouldn’t admit the truth to her. “And why didn’t he tell me this before we got married?” Back then, they both didn’t fully understand the difference between sexual orientation, gender identity, and gender dysphoria. After a difficult month of trying to process this news and wandering the aisles of local bookstores and libraries to pour over whatever literature she could find in search of answers, Mary Ann informed Dave, “I can’t change who I am, and I’m not attracted to women. This isn’t going to work for our marriage.” She figured he would do the “right thing” because he had always done so in the past. Being raised in the church, and being a teenager during the 70’s, it was taught that being gay was a choice, it was so black and white. This is something you can choose not to do. So the two shelved the topic for over two decades, never bringing it up or discussing Dave’s confession. She figured he had control over it.

Yet over the last ten years, as Mary Ann began meeting people from the LGBTQ+ community and hearing their lived experiences, her perspective began to shift. She learned that transgender identity was not a flaw or a choice, but an aspect of human diversity. Slowly, her heart softened. The realization eventually came that the hidden part of Dave’s soul—Jennifer—was not a betrayal of their love but a long-suppressed truth that needed to be acknowledged. It was in 2018 that Dave came forward a second time, revealing his authentic self as Jennifer. This time, the revelation carried with it both shock and sorrow—as Mary Ann recognized the pain Dave had suffered suppressing this side of him for so many years. It also caught her by surprise and many conversations ensued. She did a lot of soul searching to understand her own feelings and how to make things work in her marriage.

In 2020, when they felt it was time to tell their children and their spouses, Mary Ann was concerned how they would receive the news. She knew they would be surprised and shocked because she remembered feeling that way the first time she found out about Jennifer. It took time for their children to process the news and to their credit they led with love, acceptance, and curiosity. Each child was concerned with how their mom was coping with this change. Mary Ann appreciated their checking in with her. The Andersen grandchildren, accustomed to the familiar image of their granddad gradually were introduced to Jennifer and soon began to accept this new reality.

Their oldest son, Blaine, shares this insight about his journey. “Prior to my father revealing to me that he was part of the transgender community, I had recently chosen to leave the comfort and security of my Mormon-influenced worldview. Part of this process involved the painful re-evaluation of what I once believed to be etched in stone. My soul dragged my mind to a state of intrepid curiosity. This beautiful ‘hell’ I found myself in was the ideal climate for learning that my parent had far more dimension than what was previously known. Knee jerk, black and white thinking had been replaced with an ability to see nuance and adjust focus, which I had control over. I was able to give myself permission to explore the world through his/her eyes without the crippling fear that I was on the wrong side.” Knowing that her family continued to love and support them lifted a huge burden from Mary Ann’s soul.

Blaine continued, “When a person comes out as trans, it’s important for all affected parties to have compassion. My initial reaction was that of acceptance, love and curiosity. But to be sure, I have dealt with feelings of loss and second guessing along the way. I admittedly have many more miles to cover on this journey and I have made peace with the idea that it's okay to feel a range of emotions. Patience, humility, love, and curiosity have been effective checks and balances for me. My father and Jennifer are both amazing. They are incredibly courageous and loving. Members of the LGBTQ+ community add a depth and spirit that is badly needed in our world.”

Mary Ann says that, “Now that Jennifer is out, we laugh more. We can be ourselves, and are more relaxed. We definitely communicate better.” Mary Ann laughs at how with her spouse alternating throughout the week between presenting as Dave and Jennifer, she avoids name confusion by calling her spouse “Babe.”

Mary Ann has found that the outside world, particularly the church and some segments of their broader community, have been slow to offer support. In church circles, Mary Ann was often asked hurtful questions like, “Why do you stay in your marriage?” Or “What’s wrong with you?” instead of questions she’d prefer like, “How do you make it work?” She does appreciate some LDS friends and others who have remained loyal and caring, and who often open conversations with her and others by modeling the welcoming words, “Tell me more.”

In their former stake, where news of Jennifer’s emergence spread like wildfire, some of those who the Andersens once considered friends began to distance themselves, and invitations to gatherings dwindled. For a variety of reasons, Mary Ann stopped attending church services altogether. This happened well before Dave began attending church as Jennifer in 2022. Now, neither attend LDS services, instead preferring to attend another more welcoming congregation in town.