lift+love family stories by autumn mcalpin

Since 2021, Lift+Love has featured hundreds of Latter-day Saint LGBTQ individuals & families (and allies), each with their own unique experiences. Each Lift+Love family story is written by Autumn McAlpin, who interviews each individual/family and publishes their story with the express permission of each person identified in the story and/or photos. Interested in sharing your story? Click here.

JESSICA ANGUS

Jessica Angus (she/her) has had many lives in her 32 years: missionary, ranch hand, electrical engineering student, circuit board designer, ramen shop manager, educator, tutor, and tabletop game master. She is also a transgender woman—a journey she has approached through years of careful reflection, private exploration, and spiritual inquiry.

Jessica Angus (she/her) has had many lives in her 32 years: missionary, ranch hand, electrical engineering student, circuit board designer, ramen shop manager, educator, tutor, and tabletop game master. She is also a transgender woman—a journey she has approached through years of careful reflection, private exploration, and spiritual inquiry.

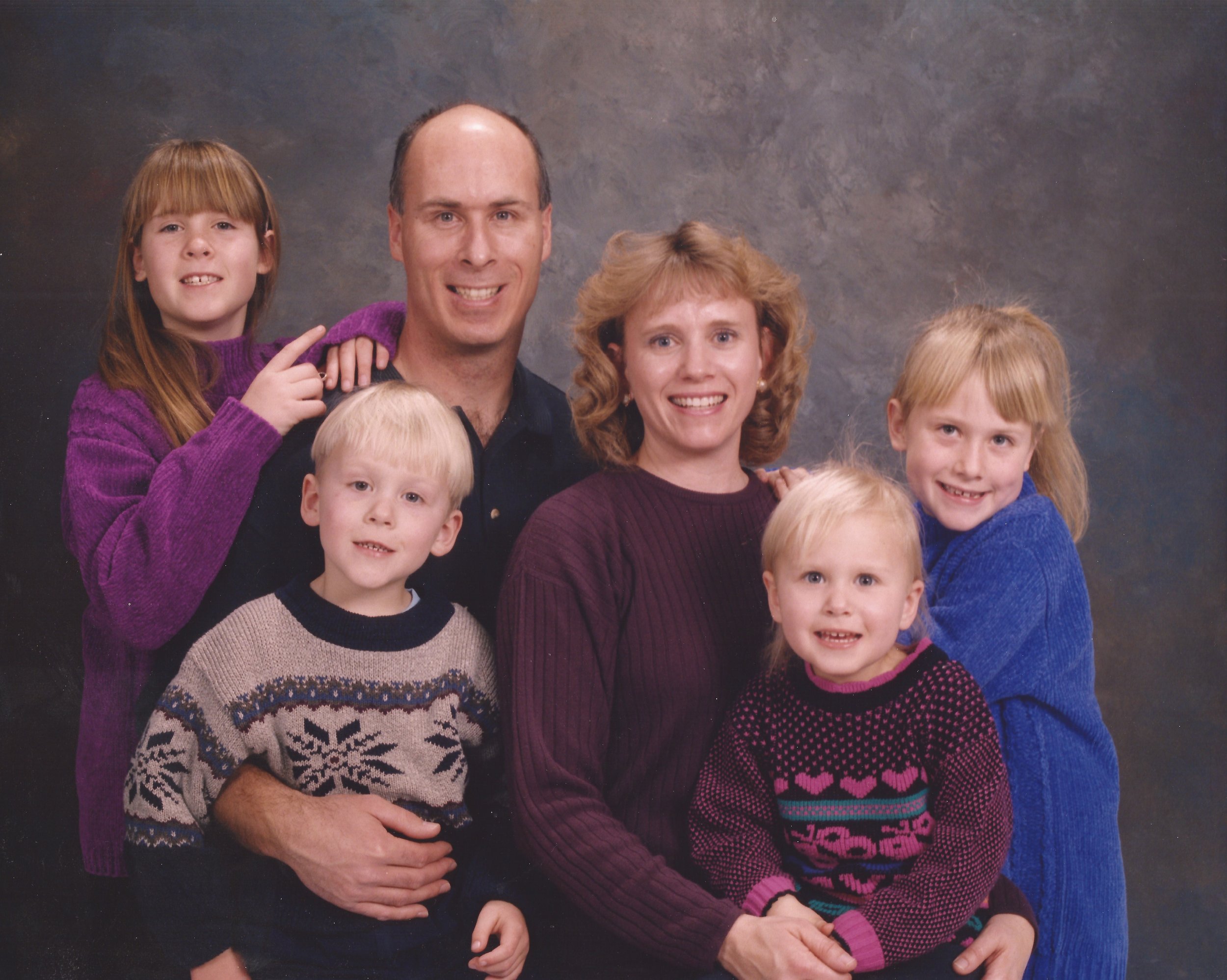

Growing up in Colorado, Jess was the third of four children and born and raised as the only boy in a family of girls. “When I was still a kid—I was ‘the boy,’ the only son,” she says. “Part of me feels like I took that from my parents, but I also found some joy in that when I came out.” While her sisters were close, she often felt left out. “Girls didn’t want to do ‘boy stuff’,” she remembers. But now they all get along well. “I love them—we communicate quite a bit.”

Her extended family is massive—her mom is one of ten siblings, and her dad is one of four. “Family reunions were huge,” Jessica says. “We’d do them all the time—my grandpa sold a business and would throw these big reunions every four years.” Jess was able to grow up knowing her extended family, some of whom have now become her closest friends.

As early as 10 years old, Jess began experiencing dysphoria, though she didn’t yet have the language for it. She’d sneak onto her my parents’ laptops, getting on the paint app and “draw on boobs” to her image, she laughs. By 12 or 14, her parents had discovered some of this behavior and labeled it “a sin” or “a fetish.” From that point on, Jessica tried to suppress everything, but it didn’t work. Rather, it only led to a path of depression—high functioning at first, then lower.

Her adolescence and young adulthood were marked by guilt and a sense of being spiritually flawed. “For 15 years, I thought what I was doing was bad—so I’d apologize to God, but always ended up slipping back into it,” she recalls. “I would buy feminine clothes on Amazon in secret. Feel guilty. Throw them in the trash. Repent. Repeat.”

College offered independence and a turning point. Jessica attended BYU and served a mission in southern Brazil—a pivotal experience. “It was the best experience of what it feels like to serve—how it feels when close to Heavenly Father,” she says. Her mission proved to be hugely important in her own journey, helping her recognize answers to questions.

The part of Brazil Jess was sent to was considered “the Texas of Brazil”—same climate, similar culture. All were religious but many didn’t attend. Jess recalls how they’d fly their state flag above the Brazilian one because they had tried to secede. “Think knives on hip, rancher, cowboy types,” Jess laughs.

She returned to BYU after her mission, where her depression increased. Five years into an electrical engineering degree, her grades slipped and attendance dropped. Eventually, her poor attendance record led to the university asking her to take a leave to address her mental health. She says the ask was beneficial because she was wasting money paying for semesters but not getting anything done. “It gave me the added kick to take care of my mental health—and led to my whole journey.”

Jessica stayed in Provo, drawn in by the eclectic local culture ad cheap rent. She began working a variety of jobs: sales rep, para-educator, IT support, hardware test engineer, professional tutor. Eventually, she took a job as a service manager at Asa Ramen. “They proclaim we’re ‘the best ramen shop in Utah’—I’d say we’re at least top five,” she laughs. Because she was eating there all the time, she decided to work there to eat for free. As a people person, she loves that she has a job that allows much human interaction.

Between shifts, Jessica programs video games and plays Dungeons and Dragons twice a week, where she’s a game master for one session. She also runs a tabletop RPG campaign where players try to build a new civilization. Of this hobby, Jess explains, “Tabletop role play games give options to create journeys for others to participate in. It’s collaborative storytelling—I think it’s awesome.”

Coming out and into her own was a slow process. As she got treatment for depression, she decided to examine where her feelings were coming from—were her inclinations to dress as a girl a sin or something else? As she’d wear the clothes she preferred, she says she was constantly praying to Heavenly Father, “Is this baby step ok? Am I good?” And as all felt ok, she’d check in at the next step.

She came out to her siblings starting at 25, then to her parents at 27. At first, she framed it as cross-dressing. She had posted a photo on Instagram of herself in a dress—ostensibly for a teaching challenge: “If you get this many people to go to prom, I’ll wear a dress.” But the reaction was intense. When she first came out, Jess’ dad said, “My son is dead,” and walked away from the phone, followed by her mom who said, “I don’t know what to say. I just don’t know…”

The call ended in devastation. “I thought, I don’t have parents anymore, this is terrible, because I wore a dress and was happy about it.” But later that same day, her parents called back. They’d gone to visit one of Jessica’s more understanding sisters, who encouraged them to express love and support. “They told me they were sorry and that I was still loved,” she said. “They expressed confusion, admitted they didn’t know how to work around it—but wanted me to know I was loved.”

That moment mattered. “Even if they’re not the most supportive in my journey, they’re still supportive of me and love me,” Jessica says. Her dad says, “I don’t know if I fully understand,” but he always asks, “Are you happy?” Jess says she feels that’s the most important question they ask of her—instead of imposing a path.

She began HRT in 2020. At first, she thought she’d be androgynous—purposefully cause a bit of chaos and confusion: “Are you a guy? A girl? But the further I went, the happier I felt—I wanted to go all the way to being female.”

Her favorite outfit now? Jess proudly laughs: Jorts and a baggy ACDC shirt. Pair of sandals.

Jessica now finds strength in a diverse network of friends and cousins, many of whom have stepped away from the church but continue to model love and morality. She says she’s been able to grow a lot through these relationships and says, “While many have left the Church, they have strengthened my belief in things the Church teaches—especially Christ.”

When Jessica legally changed her name, her friend group threw her a gender reveal party.

She’s also found spiritual grounding in her local ward. Her bishop supports her attendance in Relief Society and has tried to advocate for her amid evolving church policies. “He listens to my pains, worries—tries to find loopholes I can get through,” she said. “He says we’re going to try to ask for an exception and as there is still no guidance on how to do so, we’ll stick with status quo until we get a result.”

The Church’s recent policy on transgender members felt like a blow. “It was kind of a punch to the face,” she says. “Instead of making trans people feel invited, it tries to make other members feel protected from trans people. It wasn’t to make sure trans people aren’t discriminated against—but how to keep trans people in line.” She says the thing she’s always loved most about Christ and His gospel was how he “sat among sinners even though people thought it was impure for Him to teach them. It’s a Christlike activity to be with people we may not understand.”

For Jessica, the response revealed a deeper problem. “I feel anything made to make people not ask questions is alienating,” she said. “A lot of friends left the Church over new info for which they felt betrayed. I feel like we shouldn’t be hiding stuff and past things that were taught.” She says one of the worst wards she ever participated in was one where everyone tried to pretend they were perfect, where they’d talk about the law of Christ and say, “Isn’t it good we’re all doing this?” But she reflects how that ward felt like one in which no one could be honest or grow in their struggles.

Even so, she remains. “All the more reason I should stay—as long as I’m present and still seen, people in my local congregation will get to see, learn, grow.”

Recently, she completed a course on self-actualization that helped her reframe her relationship to church participation. “At first, maybe I was proud of being brave for being there for people who need to know a trans person’s experience,” she says. “But I stopped and reexamined—and went back to knowing I’m here for me, for Christ. Being there for others is a bonus.”

What keeps Jess grounded is a return to the core teachings of the gospel. “A lot of fluff has been added to things—but fluff changes,” she said. “During the priesthood ban… people came up with excuses, ‘doctrine’ why. At the end, all of it was not real. All excuses weren’t the case. But one part was always the case—the love of Christ, the gospel, coming to salvation through taking His name,” she continues. “All the covenants of sacrament, baptism. I cut the fluff and go back to the core of the gospel. For everything else—I seek out God myself.”

She adds with a smile: “I can have my own fluff—the fluff God wants for me.

BEN HIGINBOTHAM

Ben Higinbotham (they/them) is gay and transmasculine non-binary. Ben says, “If I explained my personal version of non-binary to someone, I’d say, ‘If masculinity was a fork and femininity was a spoon, I’d be a spork.” Ben also sometimes has to explain their sexual orientation, saying, “When people ask what it means for me to be gay as a non-binary person, I say that I guess I’m half gay for girls and half straight for girls.” One thing Ben wants to emphasize is that being gay and/or trans is not a choice or contagious.

Ben Higinbotham (they/them) is gay and transmasculine non-binary. Ben says, “If I explained my personal version of non-binary to someone, I’d say, ‘If masculinity was a fork and femininity was a spoon, I’d be a spork.” Ben also sometimes has to explain their sexual orientation, saying, “When people ask what it means for me to be gay as a non-binary person, I say that I guess I’m half gay for girls and half straight for girls.” One thing Ben wants to emphasize is that being gay and/or trans is not a choice or contagious.

Ben remembers being about four years old and pretending to be Peter Pan in preschool. "I liked the way he looked, that he could fly, have adventures, that he helped people, and that kind of thing," they recall. Ben had a crush on a girl in the class and would ride around on a tricycle (because they couldn’t actually fly, and that was obviously the next best option), pretending to save her from pirates. "I thought that maybe if I rolled my socks down instead of folding them, to make them look poofy like the people’s socks in Sleeping Beauty, she might think of me as a handsome prince. It didn’t work.”

Growing up socialized as a girl, Ben didn’t have language for what they were experiencing. But Ben often escaped into imaginative play where they could be their favorite characters like Peter Pan, Robin Hood, Simba, Harry Potter, but never the Disney princesses. Things like bows and arrows, sword fighting, and playing with bugs were great, but pretty dresses were kind of the worst.

Ben was born and raised in Orem, Utah, in a large family that was always active in the LDS church. But from a young age, they felt a disconnect between their inner sense of self and what they were told was expected of them. As a young kid, they didn’t know what the word ‘gay’ meant, and had never heard terms like ‘transgender’ or ‘non-binary.’ Nobody was pressuring them to be queer - if anything, there was pressure to not be queer. And yet, those feelings were all naturally, instinctively there. "I didn’t have the words to describe it. But I did get the sense that it wasn’t normal, and that I wasn’t supposed to talk about it."

Ben’s first memory of queer-related shame came early: a kid in kindergarten asked if they were gay and instructed them to look at their fingernails - palm up if you were gay, palm down if not. "I had no idea what 'gay' even meant, but I figured from the kid’s tone that it was bad," Ben says.

Still, they instinctively volunteered to take on the male roles in school performances. "I always wanted to do the guy part - it was what felt the most natural." In elementary school, they were part of a Spanish immersion program. Each year, there was a cultural dance performance for each grade. There were always more girls than boys, and whenever the opportunity came up, Ben would volunteer to take on a male role. Once, a mother of their dance partner came up to them afterward and said, "I’m so honored my daughter was able to dance with you." Looking back, Ben thinks that mom was likely an ally.

In their teens and twenties, the internal turmoil deepened, but they tried not to let it show. "I was always the teacher’s pet, the (mostly) straight-A student at school, and always had the right answers at church.” They developed romantic crushes on girls, but hid the feelings. They were afraid of rejection if anyone - especially those friends - ever found out. “I thought, 'this is a trial I can handle by myself. I don’t want to burden anybody - I’m the one who’s broken, so it’s my job to carry all of the discomfort.’" Ben thought they were alone. "I thought being queer was super rare. I didn’t think a girl would ever like me back." Friendships were hard. When they had crushes on friends, they assumed those friends didn’t care as deeply in return. They had no outlet for the "spiraling thoughts" in their head. "I couldn’t talk to anyone about what I was feeling, so the thoughts often spiraled out of control. Being in the closet was very emotionally unhealthy for me."

During this time, Ben still didn’t totally have some of the words to describe what they were experiencing. One hard part of being in the closet was not being able to talk to anyone who could help make things make sense. They knew about the acronym LGBT, and tried to figure out which letter fit them best. The ‘T’ was particularly confusing, because they knew they sort of felt like a boy, but at the same time, also didn’t totally feel like a man.

Ben says that for years, they likened their queerness to a Horcrux from Harry Potter. Harry had a little piece of Voldemort basically injected into his soul. “I thought my queerness was kind of like that - a little piece of Satan injected into my soul. I figured that it wasn’t actually a part of me, it was something separate, and that when I died, it would go away - as long as I never accepted it as a real part of myself.”

Ben served a three-month mission in Nauvoo as a young performing missionary, followed by an 18-month Spanish-speaking mission in San Jose, CA. Ben reflects, "I thought a mission would cure me of being queer. I figured I’d come home, get married, and live a 'normal' LDS life." But nothing changed. "As a missionary, I realized almost immediately that my same-sex attraction wasn’t going away." The first person Ben came out to was their Nauvoo mission president. The mission president reassured them: "You’re not doing anything wrong." Ben felt better but still didn’t have language or clarity to help mitigate their emotions.

After their mission, they came out to their kind and definitely well-meaning bishop, who referred them to therapy. "I basically voluntarily went looking for conversion therapy - I thought it might help me live the life I was supposed to live," says Ben. “Thankfully, the therapy that I got probably didn’t actually count as conversion therapy, at least for the most part.” The therapy didn’t change their orientation or gender identity, but it did help them understand themselves better. "It wasn’t what I originally thought it would be, thankfully."

At BYU Provo, Ben studied music composition and audio in the commercial music program. They played clarinet in university ensembles, and toured internationally with those groups through Europe and Asia. They were also a temple worker for a time. Ben says, "I realized a lot of older sister temple workers had short hair. I’d always wanted short hair but was afraid people would think I was gay." Seeing those women helped Ben realize that getting a short haircut would probably be okay. Eventually, they got the short haircut and never looked back. "Someone told me I’d look good with short hair - I got it cut, and never plan on going back."

The pandemic gave Ben time to reflect. When in-person church started back up again, they connected with a non-binary friend who became a safe person to talk to. For the first time, they had someone who truly understood. This was the first time that Ben had heard the term ‘non-binary,’ and they realized that finally there was a term that accurately described what they were experiencing. All of this helped Ben to finally feel comfortable enough to come out publicly. Still, talking about gender identity felt harder and kind of more taboo than talking about being gay.

That friendship led to an unexpected romantic relationship with the friend’s sister. The relationship was something Ben had never planned to pursue. Ben says, "I had always told myself that I couldn’t be in a queer relationship. But itkind of just happened naturally. We’d ‘hang out’ one-on-one, and for a while I wouldn’t admit that it was a date. But eventually we realized that we were in a relationship." They didn’t tell many people. The relationship ended nearly three years ago, but it was meaningful. "The thing that I’d been taught my whole life was bad didn’t feel evil. It felt right. I was learning and growing as a person."

Through that experience and hearing stories of other queer people, Ben began to shift their view of gospel living. "I don’t think the gospel is about your orientation or gender identity. It’s about being a good person - and that’s not dependent on those things." They began to lean into the scripture, “By their fruits ye shall know them.” In considering their future, Ben figures, "If it’s bringing good fruit, it’s probably good." Now, most of the shame surrounding their queer identity is gone. Ben feels that God has been healing them - not from their queerness, but from the darkness and shame and fear.

Last year, Ben signed up for the Gather Conference. When asked for their name and pronouns, they used "Ben" and "they/them" for the first time. Ben smiles, "It felt good. It felt like me." They had long admired the name Ben, a tribute to their baby brother who passed away 30 minutes after birth. "I tended to imagine my angel baby brother as a good, caring, kind, calming person. After a while, I realized that the way I imagined him was actually my own ideal self. I also like that in Latin, the root ‘ben’ means ‘good.’ That’s who I want to be."

They prayed and went to the temple repeatedly, asking if changing their name and pronouns was the right decision. "I figured God would give an answer in both mind and heart," Ben says - “and I believe that He has, repeatedly.” In the celestial room one day, after praying about the name and pronoun change, they saw two people who they knew - one named Ben, and another who had always tried extra hard to use the right pronouns. "It felt like a confirmation."

Ben changed their name and pronouns, started wearing a tie to church, and decided to be even more open about their identity. All the while, they’d check in during prayer, asking their Heavenly Father if what they were doing was the right thing. The answers always felt affirming, understanding, and loving.

When Ben told their bishop about the name and pronoun change, the bishop was respectful and kind. Though Ben did lose their temple recommend and can’t serve in certain callings because of current church policy around social transitioning, they’ve been embraced in their YSA ward and now serve on the FHE committee. "I’m just trying to be a normal person, so people can see that trans people aren’t scary - we’re just people, and we’re here."

One of the most spiritual moments of Ben’s life came years earlier, on a trip to Israel. At the Garden Tomb, they’d hoped to get a photo of them in front of the empty tomb, but were rushed out by another group’s leader. Frustrated, Ben walked away. "I thought, 'God’s good at turning bad experiences into good ones - maybe He can do that for me here.' I decided to identify what I was feeling, and realized that I was feeling pushed aside. Then this strong, clear prompting came: ‘I would never push you aside’." It wasn’t until years later that Ben connected that message to their identity. "Even though I’m queer, God won’t push me aside. Even when well-meaning members think that’s the best way to live the gospel - that’s not God. That’s people."

Ben lives with their family and their beloved yorkie, Woofard Woodwoof (Woofie). They still play their clarinet in an orchestra as well as bagpipes, and they work at a printing shop. A couple of their siblings are also queer - a trans sister and a gay brother. Ben, their gay brother Matt, and their mother Barbara have all shared their stories on the Listen, Learn & Love podcast. Now Ben is excited to share their story with Lift+Love. They’re hopeful that their story will help others feel less alone. "It’s scary sometimes, but I’m trying to be visible, so that maybe someone else in the ward or community will see me and think, ‘Ben’s cool, not scary. Maybe other gay or trans people aren’t scary either’."

Through all of this, Ben is very grateful for a Savior who understands all of it, because He felt it along with us - and comes to us and loves us, right where we are, even in the hardest times.

You can hear more from Ben at the 2025 Gather Conference www.gather-conference.com

BRAXTON ROGELIO

Braxton Rogelio (he/him) has spent his life pursuing the arts while asking big questions—which has led him to embrace his identity as the proud transmasculine, gay man he is today…

**content warning: suicide attempt is mentioned**

Braxton Rogelio (he/him) has spent his life pursuing the arts while asking big questions—which has led him to embrace his identity as the proud transmasculine, gay man he is today.

Now 39, Braxton lives in Mesa, Arizona, not far from where he was born and raised. A passionate writer since the age of 13, he’s currently working on a memoir with the support of his uncle, who is a Utah-based author, screenwriter, and director. Their bond is built on a shared love for exploring possibilities. “He’s such a sweet, funny personality,” Braxton said. “We’re so similar—we’re always asking what if, and what else.”

Braxton’s life is rich with passions. He loves anime, karaoke, travel, and his beloved cat, Bear—a tabby-Siamese mix he describes as a “gorgeous boy and absolute love bug.” He proudly embraces his Latino roots through his dad’s Portuguese and Spanish heritage. And when it comes to music, his playlist features favorites like David Archuleta, John Mayer, and Selena.

Music, in fact, quite literally saved Braxton’s life.

A few years ago, after leaving the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and facing pressure to return, Braxton found himself in a dark place. Depression overwhelmed him. “I had been told, 'You need to come back to church,' and it just got really bad,” he says. One night, feeling hopeless, he attempted to take his own life.

As he sat alone, still suffering yet having survived the attempt, a song shuffled onto his phone: David Archuleta’s “To Be With You.” He says, “Hearing David’s song—it saved my life.”

Later, Braxton had the chance to tell David Archuleta exactly that. At a Christmas concert at the House of Blues in San Diego, he met David, shared his story, and received a hug in return. “I was so grateful,” he said. “I gave him a gift—a few things he had said he liked on Instagram—and it was great to talk to him."

Last Mother’s Day marked another turning point: Braxton came out publicly as trans. While he had long stepped away from church activity, the day offered a bittersweet illustration of the complicated ties between faith, family, and identity.

His mother, still active in the church, asked him to attend services with her. Braxton agreed, despite his deep discomfort. "I was already in tears but thought, 'I'll suck it up for my mother.'" During the meeting, young children were handing out flowers to mothers. Braxton, who does not identify as a mother, was encouraged by his mom to accept one. "I thought, ‘this is so weird’," he said.

Later, attending a Relief Society meeting only deepened his feelings of isolation as Braxton had fully embraced his identity. “Ever since I was five or six years old, I knew something was going on,” he said. “I even told my brother when we were little kids, 'Hey, I'm your brother’."

Coming out to his family brought a range of responses. His younger brother, two years his junior, was the first person he told. “He wasn’t surprised,” Braxton said. “He said, 'You've always identified that way. As long as you're happy.'"

His sister, who is three years older, and his father were also supportive. His father’s response was simple and unconditional: "No matter what, I'll always love you."

Today, Braxton enjoys close relationships with his father and stepmother—whom he affectionately calls "Mama"—as well as with his brother and his brother’s family. "Everyone lives in Arizona,” he said. "My dad and Mama have lived in the same house for 25 years. My brother and his wife and five kids live just down the street."

While most of his family offers love and acceptance, there have been painful exceptions. But Braxton focuses on the love that surrounds him. “I have a good support system and love them very much,” he said.

Braxton’s journey of self-discovery has also included navigating relationships. Over the years, he’s experienced three failed engagements. Each time, he realized he couldn't move forward without first fully understanding and accepting himself. “It had to do with me, not them,” he reflected. “I couldn’t help them the way they deserved, not with everything going on inside me.”

Today, Braxton also identifies as demisexual or asexual, and finds belonging within the ace community. Trying to live authentically hasn’t been without its challenges. Braxton has faced harsh words, including being told he was “evil” or “being seduced by Satan.” But he stands firm in who he is and trying to be. “With everything going on in the world, don't be afraid,” he says. “Embrace yourself. You shouldn't feel ashamed. You deserve to be yourself.”

Looking ahead, Braxton says, “I hope to be a man married to another man,” he said. He feels a strong connection to his Latino heritage and hopes to build a life that honors all parts of his identity. He’s also working toward greater mental health support, planning to join a group therapy program through AZ for Change, an organization supporting LGBTQ+ individuals.

Music continues to be a source of healing and joy. Braxton eagerly looks forward to attending upcoming David Archuleta concerts—including two in southern California this week. “I'm excited to meet up with some friends there,” he said.

In the meantime, he continues writing, learning to play the piano from his mother, and pursuing his dream of publishing his memoir—which he hopes will prove a testament to a life defined not by fear or conformity, but by authenticity, resilience, and love.

AUBREY CHAVES

Aubrey Chaves has mastered the art of asking questions. As the co-host, alongside her husband Tim, of the popular Faith Matters podcast, Aubrey is known for her curious spirit and ability to ask complex, thoughtful questions of her guests, who range from scholars and theologians to therapists and philosophers. The conversations she helps lead are not surface-level; they probe deeply into the experience of faith expansion, and often, faith crisis…

Aubrey Chaves has mastered the art of asking questions. As the co-host, alongside her husband Tim, of the popular Faith Matters podcast, Aubrey is known for her curious spirit and ability to ask complex, thoughtful questions of her guests, who range from scholars and theologians to therapists and philosophers. The conversations she helps lead are not surface-level; they probe deeply into the experience of faith expansion, and often, faith crisis.

Her instinct for asking good questions stems from her own period of deep questioning. Around 2011, Aubrey’s husband read Rough Stone Rolling by prominent LDS scholar Richard Bushman, and it shook their world. Aubrey had picked up the book to better understand her husband’s wrestle as he sought answers as to how best to defend the church, but instead found herself devastated by its contents. She says, "It forced me to face questions I’d ignored so long because I thought if a question disturbed me, it must be from an outside source or not true."

What initially disturbed her most was church history, but over time she became even more troubled by the present-day implications—particularly the harm she saw in the church’s position on LGBTQ+ issues. History, she realized, was static, but current doctrine and policy were not. "I felt disturbed by some of what I read that I couldn’t explain—some things that were not doing active harm, but the position on LGBTQ was doing active harm."

Aubrey had long believed that the truthfulness of the church meant it was always aligned with God's will. But once that certainty began to crack, the weight of being complicit in harm became unbearable. She felt a sense of urgency to decide whether to leave or stay. She entered what she calls a "season of consumption"—a six-year period of reading, learning, and trying to resolve the dissonance. Eventually, she became more comfortable with uncertainty. She realized there might never be a single answer that could make everything feel tidy again.

With that realization, she began to redefine the church’s place in her life. Rather than seeing it as a source of all gifts and truth, she started to view her relationship to it as one where she could offer her own gifts and energy. Discovering the Faith Matters community and being asked to take over the podcast along with Tim emerged from this shift—a space to pour her energy into thoughtful conversation. She recalls, “It came about organically because we felt so desperate for connection, to find people asking similar questions and burdened by similar pain.”

Aubrey sees ongoing tension around LGBTQ+ issues as a large part of the necessary struggle. Though she wishes the church were doing more, she believes in the power of creating bridges through honest dialogue. One conversation that stayed with her was with LDS scholar Terryl Givens, who told her, "Sometimes we make an idol of our own integrity." That sentiment helped her understand why she continues to stay and engage, even when doing so is painful.

There have been many moments when it would have been easier to walk away. But she believes there’s value in remaining at the table, asking questions, building trust, and staying in difficult conversations. "I've stayed in the church to stay in the conversation—even if I'm in an excruciating conversation or at a table where we're not all aligned."

Aubrey has often felt conflicted about that choice. There were times when integrity seemed to demand something more finite—like leaving altogether. But she believes that defining integrity in such narrow terms might not capture the full picture. “Maybe we don’t always have to do all or nothing,” she reflected. “People feel a call and energy moving them to where they’ll be able to do the most good for their soul or community. For me, I felt it was okay to stay and be very uncomfortable—a calling to put my gifts and energy here.”

It took years, she said, to feel peace in that lack of alignment. But over time, she found that her discomfort became a source of transformation. “I use my gifts to push toward real change— trusting that transformation within my own circle of influence can create meaningful ripples.”

She describes the Faith Matters experience as one of healing and exchange. “It feels like healing flowing—we’re recipients as much as we put out,” she said. In the most honest conversations, even between people who completely disagree, she has seen something almost mystical happen. “There’s a magic moment where people are being vulnerable, honest, coming to the table in good faith, to connect. The technicalities of where you fall on one issue aren’t quite so loud because of this connection. The energy is so much softer.”

This shift, she said, feels worlds away from the “angsty arguments” that once left her feeling defensive. Instead, there’s a more grounded compassion, a willingness to understand.

In recent years, as Utah legislation has taken sharp turns that many have found painful, Aubrey has also felt the weight of needing to respond. “It never feels like enough to say our hearts are hurting, too, in Utah,” she said. “But whenever church things come up, I hope people feeling the most vulnerable and raw know that those of us who feel more safe are using our privilege. I hope it’s some comfort.” She sees her role as someone who can use her voice to open doors. “I’m hoping to be a resource—to get into a room for someone with a harder path. I hope they feel a sense of solidarity. I’m here, with linked arms.”

A large part of Aubrey and Tim’s allyship journey began while they were living in Boston. They developed a close friendship with a married gay couple—neighbors and classmates of Tim’s in business school. These friends, without ever explicitly trying to teach or convince, helped Aubrey and Tim see that their lives were fundamentally the same. Through genuine friendship, any lingering resistance Aubrey had simply dissolved.

"It was the universe’s gift to us," she said. "While asking big questions, we had this steady handful of friends. It was a totally unspoken way of breaking down any remaining barriers. They evaporated because we loved these people so much."

By the time they returned to Utah, Aubrey felt deeply committed to helping the church become more aligned with the inclusive spirit of Jesus. That experience solidified her sense of purpose. It also helped Aubrey and Tim learn how to be a safe space for others, especially for LGBTQ+ loved ones who later came out. They want to always be the kind of people who radiate unconditional acceptance.

In their Midway, Utah home, Aubrey and Tim are raising four children, ages 16 to 7. From the beginning, they’ve tried to make LGBTQ+ inclusion feel joyful. Each year, they go all out decorating for Pride month, turning it into a family celebration with rainbow-themed treats and signs.

Over time, their children have come to see LGBTQ+ identity as something to celebrate. Their youngest child doesn’t even recognize there might be tension around the topic. For her, learning someone is LGBTQ+ is simply fun and good news.

As their kids have grown, Aubrey has seen how these early efforts shaped them. They’ve formed meaningful friendships with LGBTQ+ peers, who often recognize their home as a safe space just by seeing a rainbow decoration or a photo from a Pride event.

One of the most powerful moments of visceral change in recent years came during last year’s Faith Matters Restore gathering, where Allison Dayton and John Gustav-Wrathall led a session together. Aubrey remembered watching the energy in the room shift as John shared his story. The audience, many unfamiliar with John or his journey in and out and back into the church while being married to his longtime partner, leaned in with openness and empathy.

John’s decades-long effort to seek fulfillment while holding on to what was important to him resonated deeply. Even attendees from more conservative backgrounds responded with compassion. Aubrey said it felt like "4,000 people leaning in together."

Faith Matters surveyed its audience, and LGBTQ+ inclusion ranked among their top concerns, alongside women’s issues. Most of their listeners are still active in their wards, navigating tension as they show up with love and faith. Aubrey hopes those who are struggling know they’re definitely not alone.

Reflecting on how to handle difficult conversations, Aubrey draws inspiration from Jonathan Haidt’s book, The Righteous Mind. She’s learned that trying to persuade through logic is rarely effective. Instead, she finds that storytelling and connecting at that heart level are always more productive for good.

By sharing what is honest and painful instead of confronting or creating tempting arguments, she has seen conversations shift and “connection across the table that does so much of the heavy listening.” It’s then that Aubrey knows, “Seeds are planted in those moments—and that is the most fertile ground for good fruit.”

Aubrey Chaves will be presenting at this year’s Gather Conference. To register, go to: www.gather-conference.com